Legislation

Description

This section is from the book "History Of American Beekeeping", by Frank Chapman Pellett. Also available from Amazon: History Of American Beekeeping.

Legislation

The first record of an attempt to control bee disease by legislation is an act for San Bernadino County, California, passed in 1877. This was the forerunner of a general law passed by the California legislature in 1883, which provided that the board of supervisors of any county was authorized to appoint bee inspectors. The law provided that the board should fix the compensation of the inspectors to be paid from county funds. The law required that the bees found to be diseased should be burned the following night, together with all hives and combs, or that such equipment should be buried in the ground. The law also required that any beekeeper finding disease in his apiaries should at once destroy all diseased colonies by the method mentioned above.

Probably the first bee disease law of state-wide application was passed by Michigan in 1881. This law, likewise, made it unlawful to keep any colony of bees affected with foulbrood and provided that such diseased colonies should at once be destroyed by fire or interment. It was in effect for many years before provision was made for inspectors with state-wide authority.

It is interesting to note that these laws were passed before disease was widely distributed, and that no provision was made for treatment of diseased colonies. Burning was the first method prescribed for dealing with bee disease, and stringent laws were passed in two of the states where commercial beekeeping was developed.

At that time beekeepers had not learned to distinguish between European and American foulbrood. The bee magazines were filled with correspondence regarding foulbrood, as though there was only one form of the disease, although there was an occasional reference to "malignant foulbrood, " indicating that at times it was more difficult to control. In the old magazines there are numerous reports of cures of the disease by the use of salt, soda, coffee, and other similar agencies. These successes are accounted for by assuming that it was Sacbrood or European foulbrood which thus disappeared following treatment. Since it was not known that there were three diseases, the laws required the burning of colonies in any case.

In 1889 Dr. C. C. Miller wrote that if all his bees were diseased he would try some of the cures, but that if less than ten per cent were diseased he would burn up the whole outfit. It had been known for long that it was possible to save the bees and equipment by shaking the bees into clean hives and destroying the combs. Several writers, notably G. M. Doolittle, began to advocate this practice.

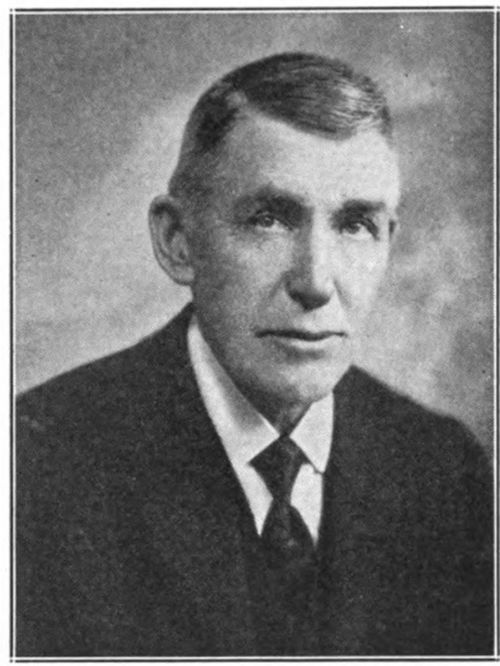

N. E. France was the first bee inspector for Wisconsin.

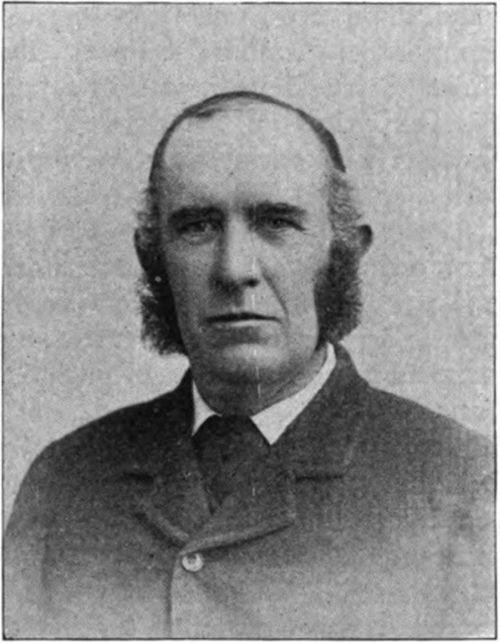

In 1891 the province of Ontario, in Canada, passed an act for the suppression of foulbrood, and Wm. McEvoy was appointed inspector. A new figure now came into the limelight, for McEvoy endeavored to rid the apiaries of the disease without destroying the property of the beekeeper. He practiced the shaking treatment already known to well-informed beekeepers and it was widely disseminated under the name, "McEvoy treatment. "

In 1897 the state of Wisconsin passed a law patterned after the Ontario statute and N. E. France was appointed inspector in charge. France, like McEvoy, advocated treatment rather than burning, and thus treatment came into popular favor. By this time the details of successful treatment were well understood, and success followed the efforts to eradicate disease in hundreds of apiaries.

France was an active and energetic leader, and Wisconsin soon set the pace for other states to follow. One after another passed laws similar to those of Wisconsin, and no thought was expressed of attempting to eradicate bee diseases by any other method.

It was not until 1912 that Iowa passed a disease control law, and the writer of this book was appointed inspector.

After a few years of effort, the writer became convinced that permanent eradication of the prevalent bee diseases was very improbable, if not impossible. In the 1916 report appears the recommendation to combine extension work with inspection in the Extension Service of Iowa State College.

The writer contended that disease eradication is more a matter of education than of police power. While the changes were made as recommended, and inspection has since been combined with educational work in Iowa, that plan did not meet with popular favor elsewhere. The trend has been in the other direction, and there has been created a popular favor for returning to the original method of burning all diseased colonies.

Within recent years nearly all the states have made some provision for bee inspection, and but little that was original or new has appeared in connection with the bee inspection work. It has settled into rather definite routine with constantly mounting appropriations.

Although inspectors have given their best efforts to eradicate disease, but little progress of a permanent nature has been apparent.

By adopting the area cleanup plan, certain districts have been cleared temporarily of the disease, but it commonly appears Wm. McEvoy became bee inspector for again after a longer or shorter period in the province of Ontario in 1891.

Some very sincere effort has been made to make a showing in this field, and a great reduction in the percentage of disease has been shown in many states. This has been maintained only by constant effort and frequent reinspection, with nothing more than temporary benefit to the time of this writing.

Continue to: