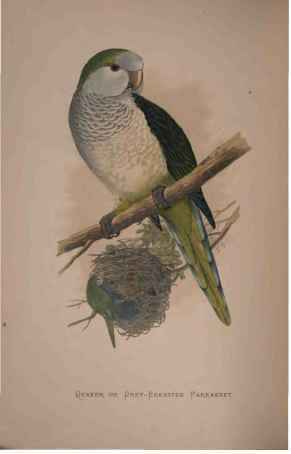

Quaker, Grey-Breasted, Or Monte Video Parrakeet. Psittacus Monachus. Bolborrhyncus monachus, Psittaca calita, Myiopsitta murina

Description

This section is from the book "Parrots In Captivity", by William Thomas Greene. Also available from Amazon: Parrots in Captivity.

Quaker, Grey-Breasted, Or Monte Video Parrakeet. Psittacus Monachus. Bolborrhyncus monachus, Psittaca calita, Myiopsitta murina

Psittacus Monachus. Synonyms: Bolborrhyncus monachus, Psittaca calita, Myiopsitta murina, etc.

French: Perruche Souris.

German: Mönchspapagei oder Quäker.

PERHAPS the most curious fact connected with the natural history of the Psittacidœ, is the nidificating instinct of the Quaker Parra-keet, which, departing from the general habits of the genus, builds itself a nest of sticks among the branches of a tree; while all its congeners make their breeding burrows in the hollow limbs or trunks of trees, or, in a few instances in the ground, or under the roots of a tree.

The nest of this bird is a very large structure, composed of the long thin terminal branches of trees, which are in-laced so firmly by the builder, that it is quite a difficult matter to tear one of them to pieces; it is domed like the nest of a magpie, and has usually two openings, one perhaps for entrance and the other for exit.

In captivity the same habit is retained, at least in the generality of cases, for M. Rousse, whom we have already quoted in another connection, relates, that his Perruches Souris were in the habit of filling up their nest-boxes with every thing they could find; "remplissent leurs nids de tout ce qu'elles trouvent;" whereas those in the possession of the present writer, although they had numerous nest boxes at their disposal, refused to have anything to say to them, but covered over a seed box with the twigs taken from a birch broom; of which domestic implements they used up three before the nest was finished to their liking. The shallow box was first filled with twigs, cut in suitable lengths strongly matted together; and then roofed over with longer branches very firmly interlaced. In the first instance a door-way was left in the side of the nest facing north, but the birds finding, apparently, that this exposed them too much to the weather, deliberately cut another doorway facing west, and then filled up the former opening; closing it completely with an extra thickness of twigs.

They made use of no softer material for lining their abode, in which, although no eggs have been laid, both male and female pass the night and a great part of the day, but made the floor of the nest of small twigs; reserving the larger for the sides and roof.

Owing to the position in which the box was placed, the shape of the nest is flat, instead of being round, as usually happens when the birds are at full liberty; but to render it more secure they have threaded a large number of sticks through the wires of the aviary, close to which the box happened to be placed. Before finally selecting this situation, the female made several attempts to build in other places but soon abandoned them; and after her nest was fairly under way, made use of the materials she had already collected elsewhere to complete it.

It would be extremely curious and interesting if any one could find out why these birds have so widely departed, in the matter of nest building, from the habits of the race to which they belong; but that is a point that will probably never be satisfactorily cleared up, so that we must, perforce, remain contented with our ignorance. A correspondent has suggested, that perhaps instead of having taken a new departure, Monachus may be the only Parrot that has persisted in the old custom of nidification, once common to all its congeners; but this view we take to be extremely unlikely. Indeed it stands to reason, we think, that a universal change of the habits of a race, with one solitary exception; is less likely, far less likely, to have occurred, than that one member of that race should, from whatever cause, have worked out a new line of action for itself. Be that as it may, it is little less curious that in captivity the habit should have been occasionally departed from, as happened in the case of M. Rousse's birds; "qui remplissent leurs nids de tout ce qu'elles peuvent trouver" as he repeats in another part of his book on "Aviculture."

Mr. Sydney C. Buxton, of Fox Warren, Cobham, Surrey, relates in the Animal World for 1878, page 179, the history of a pair of these birds that were in his possession at one time. "Five years ago I brought back from South America, two small green paraquets, which I had taken when young from their nests. These two little birds became very tame and familiar; and it was a pretty sight to see them hovering, humming-bird-like, in the air and pecking at a lump of sugar held in one's hand. Like all the paraquet tribe, however, they would not allow their heads to be scratched - the one thing above all others that a cockatoo considers blissful. These two were turned out about September, and early in October they began to build a nest on the top of a large vase, which stood in the open hall. Of course, according to their calculations, the spring should have been well forward by October. They must have thought the winter unaccountably mild, and the spring and summer too disgustingly cold.

"The nest was formed of silver birch twigs, twined and matted together making one solid mass. The tiny birds looked very graceful flying into the hall with a long sprig of birch trailing behind them. Once, when the nest was almost three feet high, the whole of it was blown down, but they did not seem to mind, and when it was put up again they went on adding twig to twig as if nothing had happened. During the process of building they unmercifully attacked any birds that attempted to come near the precious nest. One old cockatoo had to be kept indoors, so savagely did they attack him; and the doves, who also inhabit the garden hall, had anything but a pleasant time of it. Unfortunately (in January,) before the nest was finished, we had to come up to London, and one day, very soon after we had left, the birds disappeared; the nest, as then left, was some five feet high and about six feet in circumference at the top. The birds never shewed any desire to lay eggs, but probably when the warm weather came they would have made some use of their stupendous erection."

From the above interesting account of what we presume to be Quaker Parrakeets, for we are not aware of any other American species that build nests of twigs; we gather, first, that the little architects, which by the way are as large in the body as a Bengal Parrakeet, and with larger heads, were young and inexperienced; or, instead of going on heaping twig upon twig until their edifice attained the enormous dimensions stated, they would have roofed it over before it had reached one quarter of the size, and have finished it off as neatly as our own birds have done, and with greater elegance, no doubt; for they had green twigs to work with, and our Parrakeets, dry and consequently inelastic branchlets only.

Mr. Buxton calls his birds "tiny," but the Quakers can scarcely be so designated correctly, except as compared with the large cockatoos and macaws of which this gentleman had a goodly stock at the same time. His birds seem to have been somewhat quarrelsome and aggressive in their habits, but we have never noticed that ours interfere with their companions, or even resent their approach; in fact some impudent greenfinches that inhabit the same enclosure actually sit on some of the projecting sprigs of birch of which the nest is built, without the Quakers molesting them in the least, or indeed taking any notice of their presence. A pair of New Zealand Parrakeets too run over the nest in their quick mouse-like fashion, without, as far as can be detected, provoking the resentment of the owners; who, possibly, may be a particularly even-tempered pair. They are not very young we know, and that may account for their superior skill in nest construction, no less than for their amiable and forbearing disposition; for youth is apt to be resentful at times, and mature age, not senility, is, or should be, more tolerant. Birds, too, like men, gather wisdom by experience, whence the superior architectural skill of our pair, which certainly greatly exceeds that of their youthful compatriots at Fox Warren; for the former work with an evident object in view, which the latter apparently lacked.

A nest five feet high, and six in circumference at the top, must have taken a goodly number of birch twigs to construct, and the havoc wrought among the surrounding trees must have been considerable. Needless to mention, that it would bo perfectly useless to plant trees or shrubs in any space where a pair of Quaker Parrakeets were confined.

"Quaker"? Why are these birds called by the popular designation of the estimable people who name themselves "Friends"? It is difficult to say; but possibly on account of the fact that the head, throat and breast of these birds is of that delicate pearly shade of grey, so often affected by the lady members of that Society; but there the resemblance ceases, for the remainder of the plumage is bright grass green excepting the flight feathers, which are blue. The beak, somewhat large for the size of the owner, is white, horn-white, with a slight shade of brown. The legs and feet are lead colour, and the former are short and stout, indicating arboreal habits.

Azara, who first described these birds, gave them the name of "Young widows, because no Parrots show such an amount of smart and coquettish ways as these," which, it must be confessed, is a little hard on the ladies. Azara, however, may, on the whole, bo considered a reliable authority, and although his first account of these nest-building Parrots was received by naturalists with incredulity; his observations have since been amply confirmed by subsequent travellers in the same regions, of whom it will bo sufficient to name Darwin and Burmeister; as well as by numerous exhibitions of their nest-building proclivities in various aviaries and Zoological Gardens.

If the Quaker Parrot is not, as we have seen, a showy bird, it certainly cannot be recommended for its figure, which is clumsy in the extreme; the large head and thick neck being made to look larger still, by the habit of keeping the feathers on these parts ruffed up, after the manner of the domestic cat when it puffs out the hairy covering of its tail.

In captivity, that is to say in a cage, these Parrakeets will learn to speak a little, but their unbearable cries, in which they frequently indulge, are simply insupportable.

A lady of our acquaintance was possessed of a splendid Grey Parrot, a beloved and highly accomplished bird, which was the delight of his mistress, and well deserved the care and attention she was never weary of lavishing upon it; one day, however, a friend presented her with one of these wretched birds which, the moment it was released from its travelling box, commenced to pour forth a series of the most appalling shrieks, an accomplishment of which these Parakeets are perfect masters; and the Grey Parrot caught up the hideous sounds, and has repeated them at intervals ever since; much to the dismay of the lady who owns it, and the other members of the household; and that although the offending "Quaker" was speedily sent away.

It is curious that when at liberty, or comparative liberty, in an outdoor aviary, these birds should very seldom scream, but so it is, and the aviary out of doors would appear to be their more suitable destination; since they are quieter there, and being perfectly hardy, the aviarist need not fear that the cold will do them any harm. On the contrary, their plumage is much improved by the change from the cage and house; and wears a kind of bloom that is in vain looked for in-doors. Nor is this remarkable since the home of this bird is in the western parts of South America, Paraguay, the Argentine Confederation, and Bolivia; where it is found on the mountain ranges at an elevation of from three to four thousand feet above the sea level.

Bechstein, among other writers, credits the Grey-breasted Parrakeet with the faculty of imitating human speech; and Gibson, a traveller in its native land, speaks of having heard wild birds of this species crying "Pretty Poll!" as they passed by in their rapid undulating flight from their feeding grounds; which by the way to us appears to be a somewhat hazardous flight of that author's imagination. "Often," he writes, "in passing through the forests, I heard, to my astonishment, a bird of this species crying hoarsely "Pretty Poll!" We presume it was the Spanish equivalent of "Pretty Poll" that Gibson heard them say, but further comment is superfluous.

Dr. Willink, of Utretcht, a great admirer of the Grey-breasted hi. D

Parrakeets, was recently in possession of an individual of this species which, according to the account of his friend Dr. Russ, "speaks as clearly as the best Grey Parrot, but, in spite of this, has not left off its dreadful screech, which unfortunately it utters only too often."

The breeding season of these birds in their native country commences in November, and they have not as yet adapted themselves to the change of seasons in this northern hemisphere, but begin their curious nest-building labours at the same time they used to do at home; any consequently their attempts at multiplying their species in captivity generally end in failure; in the course of time, perhaps, they will understand the difference of the seasons and accommodate themselves to their altered circumstances; as many of their congeners, notably the Broadtails and Grass Parrakeets, have already in great measure done.

The Grey-breasted Parrakeet is about eleven inches in length, of which the tail measures five; it is stoutly built, and from its habit of bristling up the feathers of the head and neck, looks more bulky than it really is.

The grey feathers of the breast are edged with a line of a lighter shade of the same colour, which is wanting in young birds; and the male has a slight shade of reddish purple on his breast, by which he can be readily distinguished from his consort.

"This pretty Parrot," says Bechstein, writing towards the close of the last century, "distinguished by its silvery grey colour, is about the size of the turtle-dove. Its ruffling the feathers of its head, particularly on the cheeks, added to the smallness and peculiar way in which it holds its bill, which is always buried in its breast, gives it somewhat the appearance of a small screech owl. It is very mild, speaks but little, and even seems to be of a melancholy turn. Its call is loud and sonorous. It is the same species which is mentioned in the travels of Bougainville, by Pernetty. 'We found it,' says he, 'at Montevideo, where our sailors bought several at two piastres a-piece. These birds were very tame and harmless; they soon learnt to speak, and became so fond of the men that they were never easy when away from them.' The general opinion is that they will not live more than a year and a half if kept in a cage, but this prejudice is entirely unfounded." Commenting on the foregoing extract from the pages of the Father of bird-lore, it is only necessary to observe that these birds are still comparatively cheap, the price varying from five shillings to seven shillings and sixpence a pair; although occasionally they can be purchased for even a smaller sum than that first mentioned. The reason of this is, that they are not particularly handsome, as a glance at the illustration will shew; that they are common in their native country and frequently imported, sometimes in large numbers; nor are they favourites with those amateurs who have made their acquaintance on account of their noisy habits.

From all we have said, however, it will be gathered that could their disposition to screech be overcome, their tameness and capacity for learning to speak would soon endear them to their owners, and make other connoisseurs desirous of obtaining them; but in any case the curious nest-building propensities, and the great hardiness of these Parrakeets, are surely enough to recommend them to more favourable notice than has been accorded them of late; for there is much truth in the homely adage "Give a dog a bad name, and hang it!" as well as in the converse proposition. The Quaker Parrakeets are seldom praised by the dealers, and consequently, notwithstanding their numerous good qualities, are not very often inquired after by connoisseurs.

Our esteemed correspondent Mrs. Cassirer pleasantly accounts in the following manner for the deviation from the habits of the race, in the matter of nest building, of the Quaker or Grey-breasted Parrakeet: - "I, though a Parrot, find that as I live in bogs and marshes, the trunks of trees and branches are apt to be damp, and my young to be drowned by a sudden rising of the waters, therefore I will build on trees, and since I am good tempered and sociable, I will join my sisters for our common protection from enemies; and since I do not want to climb, I will carry up sticks in my beak, and I will line my nest with soft grass for health."

Well, that is very prettily put, and may be the true solution of the puzzle; indeed, we will go further, and say that probably it is: but so far our Quakers have not used any lining for their nest, though we have placed hay and fibre at their disposal; but may be they do not consider their edifice complete, though they sleep in it every night.

Mrs. C. Buxton writes, "You will be interested to know that, two years ago, our 'Monte Videan Parrakeets' built a nest on the top of a slender tall fir, and brought up a brood of four. We lost all but three. Next year two of them brought up a brood of five in the same nest; but we lost all these. They stray and do not return. This year we got four more from Jamrach. They were happily domesticated, and began collecting sticks for a nest, taking no notice of the old one. Then one killed itself against the windows, and two have disappeared, and now we have only one left."

The nest figured is drawn from one made in our own aviary.

Continue to: