The English Setter. Part 7

Description

This section is from the book "British Dogs, Their Points, Selection, And Show Preparation", by W. D. Drury. Also available from Amazon: British Dogs: Their Points, Selection And Show Preparation.

The English Setter. Part 7

The Pointer is a splendid dog, an admirable, a hard-working servant; he will do the practical part of his business as well as the Setter, it may be better - i.e. if you take all the Pointers in England against all the Setters. But the Setter is more than a hard-working servant: he is a devoted, a loving friend, who will go on till he cannot stand, because he wants to find game, to please himself - yes, but far more to please you. Of course this is not by any means the case with every Setter. One comes across many dogs of this breed, some of them very first class both in the field trial as well as in the shooting business, that care for nothing but the actual hunting, that would go with any one who carried a gun, and do not seemingly have any affection for any person living. Still, exceptions prove a rule.

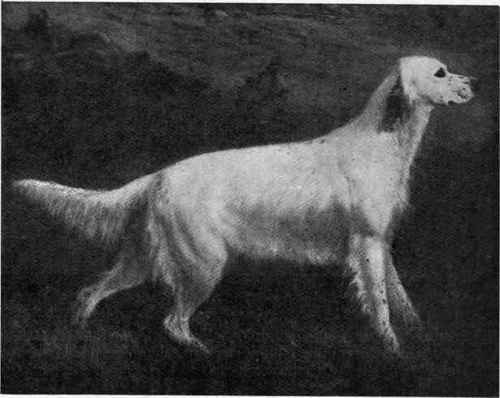

Fig. 60. - Mr. Purcell Llewellin's English Setter Countess Bear.

A few instances of the sagacity of the Setter are here recorded, though in some of the cases sagacity is far too low a term.

When the writer was a boy of seventeen, living with a private tutor, he was the proud possessor of a Pointer, and a fellow-pupil of a Setter, which latter would always go with him in preference to his master. One morning in September the writer started early, about seven o'clock, to beat a rough, distant manor over which he had the right of shooting, taking the Pointer with him. He had to walk four miles along the road, and then began to beat straight ahead. About noon he sat down on the top of a high hill commanding a full view of the beaten ground, and was regaling himself with divers sandwiches, when he noticed a black-and-white dog ranging the exact country he had been carefully beating, and of course thought at first that it was some rival sportsman who was ignorantly traversing the same ground. He looked and looked, but could see no man, and at last it struck him that the dog must be hunting him. By-and-by, as the dog topped a gate about half a mile below, the writer recognised the Setter Grouse. It was a most interesting thing to watch, as from that point he had made several wide detours in pursuit of marked birds and to beat likely fields, and so on. When the dog lost his scent he would make a wide cast like a hound and recover it, and at times, as in ploughed fields, would plod on the scent at a walk. At last he got into the big grass field where he was sitting, and with head up and stern down raced into him.

It appeared afterwards that his master thought that he would go out for a quiet shoot about noon, and loosed his dog. Grouse never even looked at him, but taking up the writer's five hours ago trail on the road, ran it at a great pace until finding him as he has described. Needless to say, the writer bought the dog and shot over him many seasons, and a most wonderful animal he turned out.

In woods, as well as in the open, the dog was first rate; in a wood he would range right away out of sight, and the writer used to saunter along at his ease with a very clever Retriever at heel. If in the course of a few minutes Grouse did not appear on his return quarter, one whistle would be given, and if he did not come then, the Retriever was told to find him. She would at once follow his trail slowly, looking back and waiting for her master at intervals, till at last she would suddenly back, and there the old boy would be, standing as stiff as a rock, and by hook or by crook the two dogs and the man would generally secure the object of attraction. If, again, one was working a river for water-fowl, the dog would take the opposite bank, if so directed, and point anything he came across, waiting until the Retriever swam over to put it up; he would never put it up himself or chase it when she did, but sit down and watch quietly what took place, and after the gun was loaded and the thing retrieved, he would continue the even tenour of his way. On several occasions, too, when he saw wild ducks on the water he would drop and hide himself and leave his master to stalk them, or, if he thought it could be done, he would make a circuit as quick as lightning, get in front of the ducks and jump into the water, barking furiously, and the ducks would thus frequently come right over the snug place where the writer had concealed himself when he had noticed the dog's tactics.

Another very clever Setter was owned by the writer when living in America for a few years. She was given to him as a puppy, made a great pet of, and was nearly always his constant companion. Not having another dog, he taught her to retrieve, which she would do perfectly both by land and water. For the ordinary prairie chicken and willow grouse work she became very perfect, and was so untiring that she would frequently accompany him on his rides of sixty to eighty miles, ranging the prairies for long distances while his horse pursued his even course along "the trail." The writer always carried a gun strapped to the saddle in a thick cover, and his saddle-bags were often full of game when he arrived at his destination.

One evening he was returning home after a long, wearying ride, and it was just getting dusk when he missed the dog. He whistled for some time and was getting uneasy, when she appeared, in a great hurry. He was riding on, when she ran in front of the horse, and stood pointing dead at him. He pulled up and said, "What's up, old girl ? Go on and tell me." She raced back in great glee, and, pointing at intervals to let him keep up, went back along the trail for a quarter of a mile, and then going into some bush on the right, stood like a statue. He was off in a moment, got a right and left at a lot of chickens, marked the rest down, luckily on the road home, and got six more of them to single points. Ever after that she never failed to carry out the plan that she had invented and had found so successful. She would range away a mile or more out of sight as her master was travelling, suddenly appear, in a great hurry, and then lead him back to some game she had found and left in order to fetch him. She would do more than this. Prairie chicken very frequently lie in belts of a willow called cotton-wood, and it is very difficult, if one is alone, to get a shot at them. This dog, after making a point in a place of this sort, would turn round, sit down, and look at her master; having thus indicated what to expect, she would make a wide circuit in the wood and get in front of the birds, which usually run away from a dog, quietly and calmly like turkeys, she would head them, "round them up "when they required it, and, pointing and drawing, would drive them quietly out exactly to the spot where her master was concealed. She very often got the whole lot thus into the open, and then would stand and look round for him; thus, of course, it was easy to get one's shot and very often to mark the covey down again. It did not, however, much matter about this latter, as if she once knew the direction which birds had taken, she was bound to find them again if you would let her, as she would go on hunting for miles in wide circles till she did.

Continue to: