Peat Moss (Moss Litter)

Description

This section is from the book "Stable Management And Exercise", by M. Horace Hayes. Also available from Amazon: Stable Management And Exercise.

Peat Moss (Moss Litter)

Origin And Nature

Peat is formed in more or less stagnant water, such as that of marshes, by the decomposition of bog plants, the chief of which is bog moss (Sphagnum). "Mosses of this genus grow in very wet situations and throw out new shoots in their upper parts whilst their lower parts are decaying and being converted into peat, so that shallow pools are gradually converted into bogs .... The formation of peat takes place only in the colder parts of the world. In warm regions the decay of vegetable substances after life has ceased, is too rapid" (Chambers' Encyclopoedia). Besides bog moss, we find among peat-producers, cotton-grass (Eriophorum angustifoliuni) and other sedges, horse-tails (Equisetum), heaths, and bog myrtle (Myrica gale). Drainage kills almost all bog plants. Peat is the first stage in the formation of ordinary coal; brown coal (lignite) being an intermediate one. The successive changes undergone by woody fibre, peat and lignite in the formation of coal, consist of a "peculiar decomposition or fermentation of buried vegetable matter, resulting in the separation of a large proportion of its hydrogen in the form of marsh-gas (CH4), and similar compounds, and of its oxygen in the form of carbonic acid gas (CO2), the carbon accumulating in the residue. Thus, cellulose (C6H10O5), which constitutes the bulk of woody fibre, might be imagined to decompose according to the equation 2C6H10O5 = 5CH4 + 5CO2 + C2 " (Bloxam). The conversion of bog plants into peat, somewhat resembles that of wood into charcoal, when it is burned in the presence of a narrowly limited supply of air.

The following table shows the respective percentages of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen in wood, peat, lignite, ordinary coal and anthracite : -

Carbon. | Hydrogen. | Oxygen | |

Wood . | 100 | 12.18 | 83.07 |

Peat . | 100 | 9.85 | 55.67 |

Lignite | 100 | 8.37 | 42.42 |

South Wales coal. | 100 | 4.75 | 5.28 |

Anthracite . | 100 | 2.84 | 1.74 |

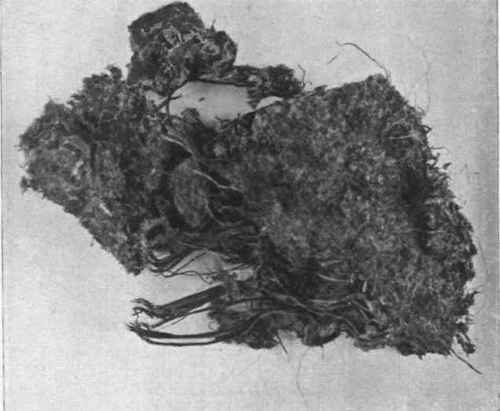

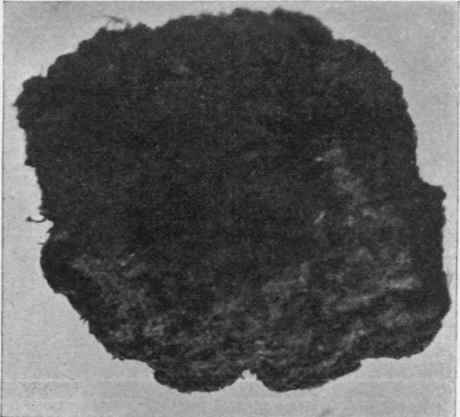

Quality And Uses

From a bedding point of view, the transformation in question is chiefly one of porosity, in which the loosely arranged stems and leaves of the bog plants gradually unite together until at last they assume more or less the character of solid stone. The stage of peat most suitable for our purpose, is an early one (Fig. 31), in which the peat is somewhat similar to wood in composition, very spongy, of a light brown colour, and light in weight. In a later stage of its formation, it is dense, heavy, dark brown in colour, and resembles lignite or even coal in appearance. This inferior peat (Fig. 32) is obtained in bogs of old formation, and contains a comparatively large amount of earthy matter. The best kind of peat for bedding purposes, has only about 15 per cent. of water, and not more than 4 or 5 per cent. of ash. Peat, like coal, ignites with difficulty as compared to wood or straw; but when properly arranged as a fire, it burns well, and throws out great heat. To test for the presence of an excess of earthy matter in peat, we may place a small quantity of the peat on an iron shovel and heat it over a fire. A good specimen thus treated will ignite when sufficiently heated; will smoulder, until it becomes gradually consumed; and will leave a light and powdery ash, which is like that of wood and which can be easily blown away.

The special advantage which peat possesses over other kinds of bedding, is its high power of absorption for both liquids and gases - a property which is naturally due to its great porosity. The larger the proportion of earthy matter, the heavier and less porous will the peat become. The presence of earthy matter also renders the peat dirty in use; especially because, when moistened with a fluid like urine, the earthy matter will form mud on the floor. When a good sample of peat is closely examined, it will be found to largely consist of fine fibres, and with no superabundance of cotton-grass (Fig. 33), the tufts of which are not very absorbent. In many inferior specimens of peat, the chief part of the contained woody fibre appears to be made up of cotton-grass.

The value of the highly absorbent properties - as regards gases as well as liquids - of peat moss is shown not only by the comparative absence of ammonia and moisture from the stable in which it is used, but also by the horses bedded on it being far more free from coughs, colds, and epizootic diseases (influenza for instance) than animals on straw, other conditions being equal. The ready absorption of ammonia, instead of being always an advantage as it ought to be, is often, unfortunately, an objection to the employment of peat moss; for careless grooms, failing to notice the hint given to them by their organs of smell, are apt to overlook the fact that the bedding requires frequent overhauling, and consequently they omit to remove contaminated portions, which injuriously affect the feet of horses that stand on them, and which sometimes leave patches of damp on the coat or clothing. Besides this, the dark colour of peat moss aids in concealing dirt, both liquid and solid, and on that account, a not very observant groom will be apt to allow a peat moss bedding to become far fouler than a bedding of straw for example. Liability to heat and to rot the horn of the hoofs is undoubtedly the chief drawback to the use of peat moss, which disadvantage can be obviated by extra care in picking out the feet and in removing soiled litter. It sometimes happens that in the use of moss litter by a groom who is careless about picking out the feet and removing tainted litter, that a horse taken out of the stable is apt to soil the yard or other places by peat falling out of his balled feet. In this case, the groom and not the bedding is to blame.

Fig. 31. Good Moss Litter.

Among other good qualities of peat moss, we may take into consideration its cheapness, portability, ease with which it can be obtained and stored, the small amount of labour required with it for bedding down and mucking-out, its applicability to the use of horses which are inclined to eat their bedding, its noiselessness when trodden on, its usefulness in filling up inequalities, such as those presented by a floor paved with cobble stones, and the difficulty of setting fire to it, as compared to straw or wood shavings. It is said that the coats of grey and white horses do not stain so readily on moss litter as on straw. On the other hand, it balls in the feet, it gives the box or stall a gloomy appearance, and is liable to block up subsoil drains which open under the animals. Peat that contains a good deal of earthy matter will of course be more or less dusty, and will consequently spoil, to some extent, the appearance of the coat for the time being. I have been strongly of opinion that peat moss tends to remove the gloss from those parts of the horse's coat with which it comes in contact; but later experience leads me to think that any influence which it might have in that direction, is insignificant from a practical point of view. Some horses eat moss litter, though not to any injurious extent, as far as I have observed and been able to learn. I therefore think that an objection made against it on that account might be passed over. I have already indicated that if the supply or frequency of change is not sufficient for purposes of absorption, a bed of peat moss will become as foul as that of any other kind of litter.

Fig. 32. Bad Moss Litter.

As peat moss quickly absorbs moisture from the air, it should be kept in bales until just before use. If, however, it has a musty smell, as sometimes happens, the bale should be opened out and dried.

Continue to: