Helm

Description

This section is from the book "The Engineer's And Mechanic's Encyclopaedia", by Luke Hebert. Also available from Amazon: Engineer's And Mechanic's Encyclopaedia.

Helm

In naval architecture, the apparatus for steering or guiding the motion of a ship. The helm is usually composed of three parts - the rudder, the tiller, and the wheel, except in small vessels, where the wheel is unneces sary. The rudder is a long and flat piece of timber, or assemblage of timbers, suspended along the hind part of a ship's stern-post, and turning upon hinges. The tiller is a long beam or lever fitted into the head of the rudder within the vessel, by means of which the rudder is turned to the right or left, as occasion requires. In order that the steersman may remain stationary, so as to see the compass placed in the binnacle, ropes, called tiller ropes, are attached to the end of the tiller, and, passing through leading blocks in the vessel's side, are pulled by the steersman; where an increased power is required, small tackles Fig. 3 are employed: but in large vessels, the tiller ropes are wound upon a barrel or cylinder, which is turned by means of a wheel set upon the same axis, and furnished with six or eight projecting spokes.

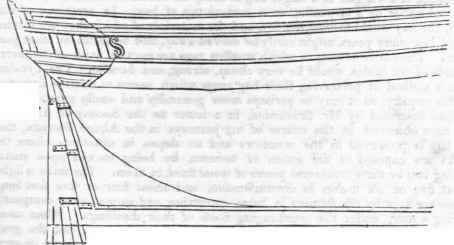

The effect of the rudder in changing the direction of a ship's head, according as it is turned to either side, arises from the current produced by the vessel's passage through the water striking more forcibly upon the side which is turned against the current, than upon the opposite side which is turned from it; and, as the rudder placed at the extreme end of a ship may be considered as appended to a lever, the fulcrum of which is somewhere about the centre of the vessel, the pressure thus exerted against it naturally causes the ship to turn upon the centre of gyration, the effect being proportioned to the velocity of the current, and to the angle at which the rudder stands opposed to it. Ships which have what is called a full buttock, that is, carry their breadth very far aft, are found not to answer the helm readily, owing to the water not coming easily to the rudder. To remedy this defect, a false stern-post is sometimes bolted on, and the breadth of the rudder increased. Mr. E. Carey, surveyor of shipping at Bristol, proposes, as a more effectual remedy for vessels having the above defect, to bolt on to the keel a piece one foot six inches abaft, running its breadth two-thirds forwards, then tapered off to nothing as far as the gripe, and to bolt another piece of equal breadth on to the bottom of the rudder (as shown in the drawings, Fig. 1 and 2, on the preceding page,) which will make the ship hold a better wind, and answer her helm quickly, and steer perfectly easy.

By reference to Fig. 3, it will be seen that the effect of the water upon the additional piece will be fully equal to that upon the whole of the rudder before it was put on; for the water rushing along the flat bottom of the vessel, and along the side of the keel, without obstruction, strikes upon the new piece with great force, and at an advantageous angle, and necessarily makes the vessel answer her helm quickly. Ships of war, and other large vessels, if they happen to strike the ground when riding heavily at anchor, or by tailing on a sand bank, are very liable to injure the rudder by tearing it away from its fastenings. To prevent this, Mr. Hillman, of Deptford, proposes that the lower part of the rudder should be made capable of sliding up into a cavity prepared to receive it, and of descending by its gravity into its original position, as soon as the vessel gets clear again. The changes in the construction of the rudder which Mr. Hill-man's plan would occasion, are represented in the subjoined figure, which is a broadside view of it. a the stern post; h part of the keel; c the rudder, the bottom of which is cut away to the dotted lines d d; f f is a metal segment, turning upon the pin g, and sliding within the case e e; this segment is made hollow from the top on two compartments, as shown by the dotted lines h h; it falls by its own weight into the position shown in the figure, and is prevented from coming further by a projection from its top, lodging on a step at i, within the case e e.

The cavity j j, from the bottom of the case e e to the dotted lines dd, is made large enough to receive the whole of the segment f f. If, therefore, the vessel should touch the ground, so as to endanger the rudder, this segment would slide into the recess, and thereby avoid the blow, and would fall out again to restore the length of the rudder when clear of the ground. The Society of Arts presented to Mr. Hillman their large silver medal for this invention.

Fig. 1.

Fig.

Continue to: