The Weibel-Piccard System Of Evaporating Liquids

Description

This section is from "Scientific American Supplement". Also available from Amazon: Scientific American Reference Book.

The Weibel-Piccard System Of Evaporating Liquids

In the industries, there are often considerable quantities of liquid to be evaporated in order to concentrate it. Such evaporation is very often performed by burning fuel in sufficient quantity to furnish the liquid the heat necessary to convert it into steam. This process is attended with a consumption of fuel such as to form a very important factor in the cost of the product to be obtained. In order to vaporize, at the pressure of the atmosphere, 1 kilogramme of water at 0°, 637 heat units are required, and of these, 100 are employed in raising the water from 0° to 100° and 537 in converting the water at 100° into steam at 100°. This second quantity is called the latent heat of the steam at 100°. The sum of the two quantities is called the total heat of the steam at 100°. The total heat of the steam remains nearly constant, whatever be the temperature at which the vaporization occurred.

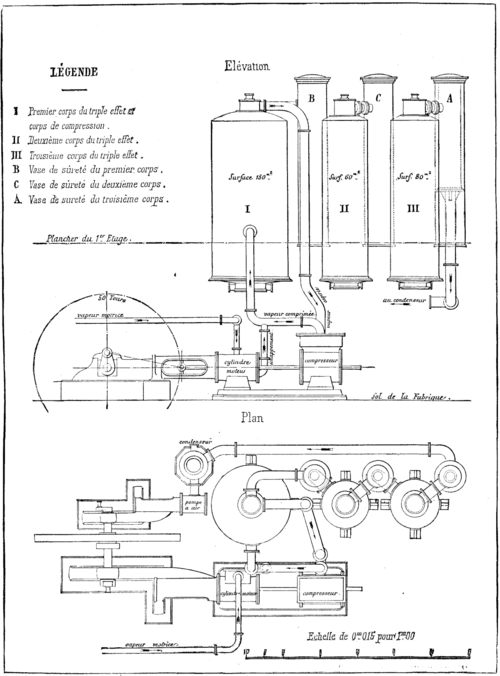

THE WEIBEL-PICCARD EVAPORATION APPARATUS.

In order to utilize the steam as a means of heating, it is necessary to condense it, that is to say, to cause it to pass from the gaseous to a liquid state. This conversion disengages as much heat as the passage from the liquid to the gaseous state had absorbed.

It results from this that if we could condense the steam that is given off by a liquid that we are vaporizing, in contact with another liquid that it is also a question of vaporizing, we should utilize all the heat contained in the steam that was being given off from the first.

This object can be practically attained by two means, viz., by (1) putting the disengaged steam in contact with the sides of a vessel that contains a liquid colder than the one that produced it; (2) by raising the temperature and pressure of the disengaged steam in order to condense it in contact with the sides of the vessel which contains the very liquid that has produced it.

The first of these means is realized in the apparatus called multiple acting, that are at present so generally employed in sugar works. The second means, which permits of a greater saving in fuel being made than the other does, is realized by compressing the disengaged steam. This compression, which raises the temperature and pressure of the steam, permits of condensing the latter in contact with the vessel wherein it has been produced. By such condensation we continuously restore to the liquid which is being vaporized the heat of the steam which it gives off.

This solution of the question, which has been partially seen at different epochs, has but recently made its way into the industries. It is being operated at present with complete success at the salt works of France and Switzerland, at those of Austria and Prussia, in the sugar of milk factories of France and Switzerland, and, finally, in 1882, the first application of it in the sugar industry was made at Pohrlitz, in Moravia.

The saving of fuel that has been made in these different applications has always been great.

We shall now, for the sake of explaining the system, give a brief description of the apparatus as used at the Pohrlitz sugar works mentioned above. These works treat 255 tons of beets per 24 hours, and obtain 4,000 hectoliters of juice, which is reduced to about 1,000 hectoliters of sirup. Up to the present, the concentration has been effected in a double acting apparatus partly supplied by exhaust steam from the motive engines and partly by steam coming directly from the generators.

In order to diminish the consumption of direct steam, these sugar works put in a Weibel-Piccard apparatus designed to concentrate only a third of their juice, or about 1,350 hectoliters per day.

This apparatus (see engraving) consists of a steam compressor, 0.835 m. in diameter, actuated directly by a driving cylinder of 0.5 m. diameter and 0.8 m. stroke, and of three evaporating boilers of the ordinary vertical tube type, the first of which has a surface of 150 square meters, the second 60, and the third 80.

The steam, at the ordinary pressure of the generators, say 5 atmospheres, is taken from the connected generators of the works, and is led to the driving cylinder, where it expands and furnishes the power necessary to run the compressor. It then escapes at a pressure of l.4 atmospheres and enters the intertubular space of the first evaporator. The compressor sucks up the steam from the juice of the first evaporator (which is boiling at the pressure of the atmosphere, without vacuum or effective pressure), compresses it to 1.4 atmospheres, and forces it likewise into the intertubular space. The ebullition of the first evaporator, then, is kept up not only by the exhaust from the motive cylinder, but also by the steam from the juice itself, which has been rendered fit to serve as a heating steam by the pressure that it has undergone in the compressing cylinder.

In this first application of the new system to sugar making, it became a question of ascertaining whether the advantage resulting from compression was of great importance, and, in the second place, whether the apparatus could be run with certainty and ease. In truth, the applications of the system for some years past in other industries permitted a favorable result to be hoped for, and the result turned out as was expected.

With this apparatus it has been found that the work furnished by one kilogramme of steam passing through the motive cylinder, from a pressure of 5 atmospheres to one of 1.4, is sufficient to compress 2.5 kilogrammes of steam taken from the juice, led into the compressor at one atmosphere and escaping therefrom at 1.4. In other words, one kilogramme of motive steam is sufficient to convert into heating steam for the first evaporator 2.5 kilogrammes of steam taken from the juice in this same evaporator. Besides, this same kilogramme of motive steam produces three effects, one in this same evaporator, and the other two in the two succeeding ones. The effect obtained, then, from one kilogramme of motive steam is, in round numbers, 5.5 kilogrammes of steam removed from the juice.

It must not be forgotten that the motive steam was at the very moderate pressure of 4 effective atmospheres. Had the use of steam at high pressure (7 atmospheres for example) been possible, it is easy to conclude from the above results that more than 6 kilogrammes of water would have been vaporized with one kilogramme of steam.

The results here cited were ascertained by accurately measuring the quantities of water of condensation from each evaporator, they soon received, moreover, the most important of confirmations by the decrease in the general consumption of fuel by the generators which occurred after the new apparatus was set in operation.

The mean consumption of coal per 24 hours for the twenty days preceding the 18th of November was 86,060 kilogrammes. After this date the regular consumption was as follows:

Nov. 19.................31,800 kilogrammes. " 20.................33,800 " " 21.................33,800 " " 22.................32,000 " " 23.................31,400 " " 24.................31,600 " " 25.................30,500 " " 26.................30,500 " " 27.................28,600 " " 28.................30,300 "

It must be remarked that in the perfectly regular running of the sugar works, nothing was changed saving the setting of this evaporating apparatus running. The same quantity of beets was treated per 24 hours, and the general temperature remained the same. This remarkable result in the saving of fuel was brought about notwithstanding the new apparatus treated but a third, at the most, of the total amount of the juice, the rest continuing to be concentrated by the double action process.

As for the running of the apparatus, that was perfectly regular, and the deviations in temperature in each evaporater were scarcely two or three degrees. The following are the mean temperatures:

First evaporator: heating steam 110° C.; juice steam 100° C. Second evaporator: juice steam 83° C. Third evaporator: juice steam 62° C. As regards facility of operating the apparatus, the experiment has proved so conclusive that the plant will be considerably enlarged in view of the coming crop, in order that a larger quantity of juice may be treated by the new process. The effect of this will be to still further increase the saving in coal that has already been effected by the present apparatus. The engraving which accompanies this article represents the Weibel-Piccard apparatus as it is now working in the Pohrlitz sugar works. What we have said of it above we think will suffice to make it understood without further explanation.--Le Genie Civil.

Continue to: