The Use Of Gas In The Workshop

Description

This section is from "Scientific American Supplement". Also available from Amazon: Scientific American Reference Book.

The Use Of Gas In The Workshop

At a recent meeting of the Manchester Association of Employers, Foremen, and Draughtsmen of the Mechanical Trades of Great Britain, an interesting lecture on "Gas for Light and Work in the Workshop" was delivered by Mr. T. Fletcher, F.C.S., of Warington.

Mr. Fletcher illustrated his remarks with a number of interesting experiments, and spoke as follows:

There are very few workshops where gas is used so profitably as it might be; and my object to-night is to make a few suggestions, which are the result of my own experience. In a large space, such as an erecting or moulder's shop, it is always desirable to have all the lights distributed about the center. Wall lights, except for bench work, are wasteful, as a large proportion of the light is absorbed by the walls, and lost. Unless the shop is draughty, it is by far the best policy to have a few large burners rather than a number of small ones. I will show you the difference in the light obtained by burning the same quantity of gas in one and in two flames. I do not need to tell you how much the difference is; you can easily see for yourselves. The additional light is not caused, as some of you may suppose, by a combined burner, as I have here a simple one, burning the same quantity of gas as the two smaller burners together; and the advantage of the simple large burner is quite as great. It is a well-known fact that the larger the gas consumption in a single flame, the higher the duty obtained for the gas burnt. There is a practical limit to this with ordinary simple burners; as when they are too large they are very sensitive to draught, and liable to unsteadiness and smoking.

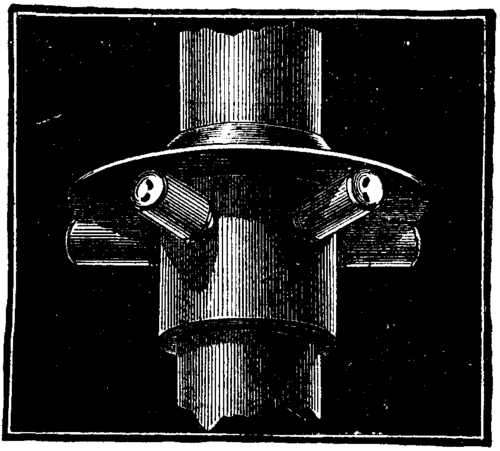

I have here a sample of a works' pendant or pillar light, which, not including the gas supply-pipe, can be made for about a shilling. For all practical purposes I believe this light (which carries five No. 6 Bray's union jets, and which we use as a portable light at repairs and breakdowns) is as efficient and economical a form as it is possible to make for ordinary rough work. The burners are in the best position, and the light is both powerful and quite shadowless; giving, in fact, the best light underneath the burners. It must, of course, be protected in a draughty shop; and on this protection something needs to be said.

Regenerator burners for lighting are coming into use; and, where large lights are required for long periods, no doubt they are economical. Burners of the Bower or Wenham class would be worth adopting for main street or open space lighting in important positions; but when we consider that, with the fifty-four hours' system in workshops, artificial light is only wanted, on an average, for four hundred hours per annum, we may take it as certain that, at the present prices of regenerator burners, they are a bad investment for use in ordinary work. We must not forget that the distance of the burner from the work is a vital point of the cost question; and, for all except large spaces, requiring general illumination, a common cheap burner on a swivel joint has yet to meet with a competitor. Do not think I am old-fashioned or prejudiced in this matter. It is purely a question of figures; and my condemnation of regenerator burners applies only to the general requirements in ordinary engineering and other work shops where each man wants a light on one spot only.

Some people think that clear glass does not stop any light. This is a great mistake, as you will find it quite easy to throw a distinct shadow of a sheet of perfect glass on a white paper, as I will show you. Opal and ground glass throw a very strong shadow, and practically waste half the light. It is better to have a white enameled or whitewashed sheet-iron reflecting hood, which will protect the sides from wind, if such an arrangement suits other requirements.

I have endeavored in the engraving below to reproduce the shadows thrown by different samples of glass. This gives a fair idea of the actual loss of light involved by glass shades.

When lights are suspended, it is a common and costly fashion to put them high up. When we consider that light decreases as the square of the distance, it will be readily understood that to light, for instance, the floor of a moulding shop, a burner 6 feet from the floor will do as much work as four burners, the same size, placed 12 feet from the floor. It is therefore a most important matter that all lights should be as low as possible, consistent with the necessities of the shop, as not only is the expense enormously increased by lofty lights, but the air becomes more vitiated and unpleasant, interfering with the men's power of working. Any lights suspended, and, in fact, all workshop lights, must have a ball-joint or universal swivel at the point where they branch from the main, as they are liable to be knocked in all directions, and must, therefore, be free to move to prevent accidents. It is better to have wind-screens, if necessary, rather than glass lanterns, as not only does the glass stop a considerable amount of light when clean, but it is in practice constantly dirty in almost every workshop or yard.

PILLAR LIGHT OR PENDANT FOR WORKSHOPS.

For bench work and machine tools, each man must have his own light under his own control; and in this matter a little attention will make a considerable saving. The burners should be union jets - i. e., burners with two holes at an angle to each other - not slit or batswing, as the latter are extremely liable to partial stoppage with dust. Where batswing burners are used, I have often seen fully 90 per cent. more or less choked and unsatisfactory; whereas a union jet does not give any trouble. It is not generally known that any burner used at ordinary pressures of gas gives a much better light when it is turned over with the flat of the flame horizontal, until the flame becomes saucer-shaped, as I show you. You can see for yourselves the increase in light; and in addition to this the workman has the great advantage of a shadowless flame. In practice, a burner consuming 5 cubic feet of gas per hour with a horizontal flame is a better fitter's than an upright burner with 6 cubic feet per hour. I do not believe in the policy of giving a man a poor light to work by - it does not pay; and I never expect to get a man to work properly with smaller burners than these. We have a good governor on the main: and the lights are all worked with a low pressure of gas, to get the best possible duty.

As a good practical light for a man at bench moulding, the one I have here may be taken as a fair sample. It is free to move, and the light is as near the perfect position as the necessities of the work will permit. When the light is not wanted, by simply pushing it away it turns itself down; the swivel being, in fact, a combined swivel and tap.

Continue to: