True Love-Stories Of Famous People. No. 11. Robert Burns

Description

This section is from "Every Woman's Encyclopaedia". Also available from Amazon: Every Woman's Encyclopaedia.

True Love-Stories Of Famous People. No. 11. Robert Burns

I nto the thirty-seven years of his life Burns managed to crowd as much contrast and emotion as would have lasted any- two ordinary men for their allotted three-score-and-ten.

Beginning as a ploughboy, he went on to owning a farm, and ended life as,an excise officer. He tasted the sweets of the most brilliant social life in Edinburgh, to which he was introduced by the Duchess of Gordon, who admired him greatly, and, according to some reports, fell in love with him. Society dropped him as suddenly and capriciously as it had taken him up, and Burns returned to a country life, where every class was numbered among his friends, and folk came from far to see him.

All this time his love affairs were going on, one after the other, and sometimes two at a time; trivial, serious, or abstract, but always passing. There were only two exceptions to this rule-that of Mary Campbell, and his affection for his wife.

The part he took in political and religious affairs made many his enemies, and one must not believe too closely all that has been said about his dissipations. He seems to have been gifted with a personal fascination which few could withstand; with good looks also, and with an impetuosity and fervour of nature which gave us many of his poems.

At the age of fifteen, while he was still driving the plough on his father's farm, reading his book the while, or thinking over poems such as afterwards made him famous -for instance, " To a Daisy" - he was paired at harvest-time with a fair-haired child of fourteen, with whom he fell in love. She was the first of a long line of divinities, who all acted more as spurs to his poetical genius than as definite personalities in his life. His brother Gilbert says that his glowing accounts of lovely girls were more than half imagination-they were mostly "moving broomsticks" round whom his fancy had thrown the glamour of beauty and virtue and imagination.

One of these affairs went further than the others. He became affianced to Mary Campbell, a really beautiful girl, who had withstood all temptations, and was as good as any poet could have imagined her. She went away to the West Highlands to prepare for the wedding, but while there she fell ill, and died before Burns could get to her bedside. From that time she occupied a little chamber of his heart wherein no other entered all his life. His love for her might have waned had they married, but her early death enshrined her in the innermost recesses of his nature. To her he wrote the "To Mary" poems, and many others were inspired by her. The humble dairymaid with the pretty face was to be made immortal by her ploughboy lover.

Shortly after this his father died, and he and his brother Gilbert took the small farm of Mossgiel in Mauchline. They worked hard, and Burns never allowed his bodily fatigue to prevent his study of literature. It was at Mossgiel that the real romance of his life came to him.

Love

In Mauchline there dwelt a master-mason by the name of Armour. He was an upright man, very religious and devout, with the almost savage devoutness of the narrow-minded. He had a daughter, Jean, over whom he watched with a gloomy affection and a fierce care for her soul's welfare. She was not exactly pretty, but she had an open face, a straight, lissome figure, and moved with delightful grace, as one might imagine a flower would walk before a gentle wind. We have it on the best authority in the world that she was " a dancing, sweet young handsome quean wi' guileless heart."

Burns was farming at Mossgiel, his heart still sore for his Mary, but sore without bitterness, for death is not an earthly rival to be scorned and hated. He was ploughing, and reading, and writing poetry, and had a gentle conviction that he had done with love (at the age of twenty-three, and he a poet !). He recognised that his " mind, it was na steady," until now; but he thought it was fixed for ever on a ghost. So he "Came roun' by Mauchline town,

Not dreadin' ony body," but

"My heart was caught before I thought, And by a Mauchline lady."

The Mauchline lady was Jean Armour, young, and straight, and merry, dancing at weddings and fairs and house-warmings, or working at home, and singing as she worked.

" And aye she wrought her mammie's wark, And aye she sange sae merrilie;

The blithest bird upon the bush

Had ne'er a lighter heart than she."

Burns fell hopelessly in love with her. His wounded spirits recovered themselves amazingly, and although he did not forget Mary, she became a sort of spiritual memory, a gentle regret. Jean was a living, present reality, and, above all, she was not nearly so much fascinated by the handsome, dreamy, poetic, fiery young farmer as her predecessors had been. No, Burns was not sure even whether she was in love with him. Naturally, he became more and more in love with her.

But trouble was brewing. He had recovered himself only too thoroughly. There was a pretty servant in the neighbourhood, and when Jean was cold, was not a man to tell another pretty girl that she was pretty? It started as the lightest-hearted comedy; it ended in tragedy, and Burns was publicly condemned by the ministers of the church.

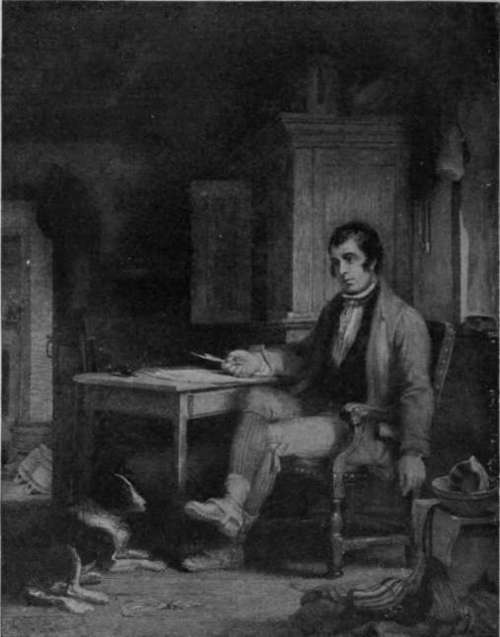

A reproduction of William Allan's charming picture of Robert Burns sitting in his cottage, writing. The romantic story of the poet's life forms the subject of the accompanying article

He ridiculed the condemnation, and that was another crime against him. Mr. Armour's disapproval became deeper and deeper.

Now, Mossgiel, the farm, belonged to the Earl of Loudoun, but the Burns brothers held it from Mr. Gavin Hamilton on a sublease. Mr. Hamilton was at open feud with one of the ministers who had condemned Burns, a rigid Calvinist, and, if one can believe the stories, not a little of a hypocrite. Burns took his landlord's side, being indeed hot-hearted against the restrictions of the Church which threatened to take Jean from him, and also having an honest hatred of hypocrisy. He ranged himself with Mr. Hamilton, and brought to the warfare the sharpest weapons of his genius. The district rang with such mordant, fiery poems as "The Holy Friar," "The Ordination," "Holy Willie's Prayer," and other bitter brilliancies. The religious peasantry took them for irreligion, when they were really directed entirely at unworthy ministers of religion. A man who loved Nature as Burns did could never be irreverent; a man who loved honesty as he did could never tolerate what he considered to be irreligious hypocrisy and narrowness. It is too often the fact that when a genius takes up sides and deals out biting satire, he is taken literally, and is supposed to be running down the very principle he is upholding.

Continue to: