Chapter VIII. Cultivation

Description

This section is from the book "The Potato: A Compilation of Information from Every Available Source", by Eugene H. Grubb, W. S. Guilford. Also available from Amazon: The Potato: A Compilation Of Information From Every Available Source.

Chapter VIII. Cultivation

The objects sought in cultivating the potato are: First, keeping the soil in the seed bed loose and retaining moisture for the crop, and, second, keeping down the growth of weeds, which, if allowed to grow, not only rob the potato plant of moisture but also of available fertility.

Moisture is taken from the ground into the air by capillary action. By cultivation the surface of the soil is broken and the evaporation checked.

Disease germs find it difficult to live and develop in soil that is exposed to the sun and air, providing there is thorough aeration and consequently plenty of oxygen.

It is not possible to farm by definite rules. Conditions change daily, sometimes hourly, so that a farmer must know what result he desires to obtain and use judgment in the time and frequency of such operations as cultivation and irrigation, and be governed by circumstances.

In an irrigation district, if ground is dry before planting, it should be irrigated well, so as to make the soil and subsoil a reservoir of moisture to be drawn on by the starting and growing plant. Some growers maintain that potatoes should not be watered after this "before planting" irrigation until the tubers are well set; that the moisture must be conserved by cultivation. Conditions may arise, however, such as a long dry spell with winds that draw the moisture from the soil, that would make irrigation advisable sooner.

In the irrigated West the crop should be cultivated deeply, soon after planting making a loose, deep seed bed. Cultivator shovels fourteen working inches long and about four inches wide, two on each side of the row, are valuable for this work. If this deep cultivation just after planting turns up the soil rough, a harrow may follow to fine the surface in order to hold moisture. The second cultivation can come when the plants begin to show. The number of cultivations depends on the condition of the soil, weeds, and number of irrigations or rains. Cultivation after the tubers are set should not be so deep nor so near the hills, because a potato torn off while in the forming stage is lost. Tearing off feeder roots or rootlets at this stage also reduces yields.

Ditches between the rows for irrigation are made with a double shovel plow attachment fastened to one beam and a two-horse cultivator. The best potatoes and the heaviest yields have been produced where deep ditching and heavy ridging have been practised. Ridges must contain plenty of dirt to protect the tubers from the sun and to prevent greening, but growing in fairly loose, well-aired soil into which the moisture comes up from the bottom has proved best. The bulk of the roots of the plant go deeper, but the tubers have the benefit of forming and developing in a favorable environment.

Flat cultivation, stirring the surface only, so as not to destroy the surface roots, is advocated in potato growing in some sections of the rain belt. There, all moisture is applied evenly over the surface in the form of rain, and it is necessary that moisture be carefully conserved for fear of drought at some time during the growing season. The available plant food is also more largely in the first few inches of surface soil than in the more loose desert soils that have had the action of the elements for ages without the packing and leaching heavy rainfall.

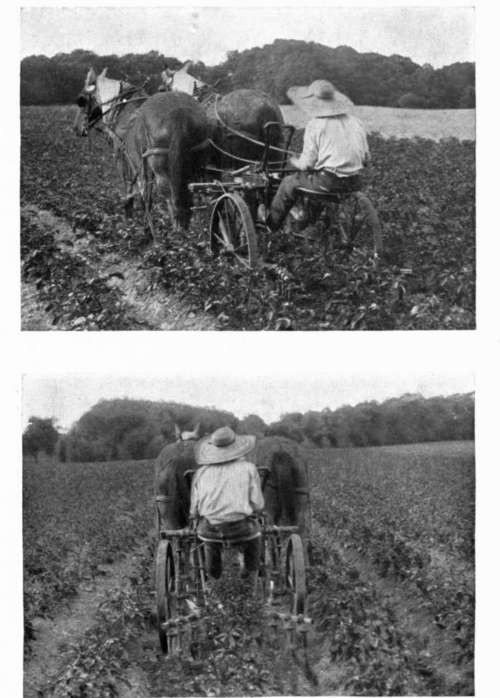

Two views of Iron Age Cultivator at work.

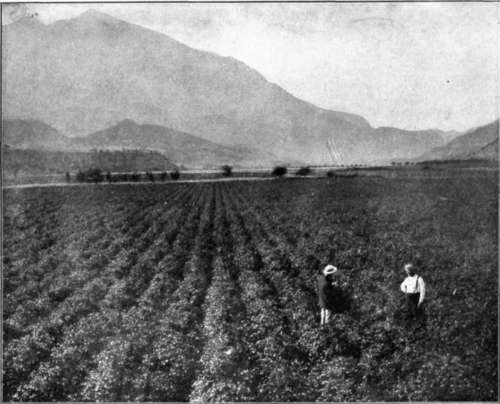

Potato field at Mt. Sopris Farm, showing how the hills are "ridged".

It is important to run the irrigation water low in the furrow to keep from solidifying the soil and soaking the tubers. The root system seems to go deeper and adapt itself to the conditions as long as the irrigation water is supplied evenly and the soil is rich. Each of these conditions is under control where the water is abundant and the soil fertile.

Irrigation is followed by cultivation, and by irrigation again as soon as necessary. This is determined by examination of the soil and the color of the leaves of the plants. If the soil about the roots is so dry it will not remain moulded with the imprint of the hand when a small handful is compressed, it is too dry and needs water. This cannot be taken too literally, but some judgment must be used even in making as simple a test as this. One novice, making this test, found that the mould he formed stood all right, but on being touched crumbled away. Literally, as he understood the rule, the test showed sufficient moisture. Actually, the ground was getting dry and, needed irrigation.

When potatoes require water they indicate it by the dark green, almost black, color of the leaves. When watered too heavily they get too light green, almost yellow. The characteristic healthy medium green of a potato plant in good condition and doing well must be seen to be appreciated, but these things are easily learned.

Good potatoes are grown with one to five irrigations, the last one not much later than August 20th, to give forty to sixty days for finishing growth and ripening. Some of the best growers irrigate alternate rows at each irrigation, taking two waterings to go over the entire field.

There is good reason why irrigation conditions are ideal for the production of potatoes. The value of this crop, as of many others, depends on a right amount of moisture at the right time, the demand for moisture being heavy while the tubers are forming and developing. In Wisconsin it is assumed that the eighteen inches of water generally counted on during the growing season is sufficient to mature a maximum crop. In ten of the past twenty-one years the amount of rainfall during the growing season has been fourteen inches or less. Prof. F. H. King, the soil expert, found at the Wisconsin Experiment Station that the addition of two acre inches of water by irrigation increased the yield of marketable potatoes 100 bushels per acre. In the Twin Falls country in Idaho and some other places in the Rocky Mountain country the moisture supply is under absolute control, making, with an ideal soil, a sufficient and legitimate reason for the production of the most perfect potatoes.

It requires from 270 to 500 pounds of water to make one pound of dry matter in the vine and tuber of the potato plant.

The best growers favor several rather light irrigations to fewer heavier applications.

In "Bulletin 132" of the Maryland Agricultural College is given the result of an experiment to ascertain whether deep or shallow cultivation would produce the best potato crop. The summary follows:

Surface.

Bu. Bu.

Primes Culls.

127.3 30.0

Medium Deep.

Bu. Bu.

Primes Culls.

137.9 30.3

Deep.

Bu. Bu.

Primes Culls.

141.6 28.2

And also the average of yields as affected by-frequency of cultivation, disregarding depth:

Five Days.

Bu. Bu.

Primes Culls.

126.5 27.4

Ten Days.

Bu. Bu.

Primes Culls.

132.4 27.6

Fifteen Days.

Bu. Bu.

Primes Culls.

147.5 33.2

In discussing it the Maryland people say: "The above figures seem to clearly indicate that the deep and infrequent cultivation was most profitable, there being a difference of more than fourteen bushels per acre in favor of the deep over the shallow cultivation, and of twenty-one bushels in favor of infrequent working. It would seem, therefore, that the practice of farmers who usually cultivate with such tools and at such times as will keep the crop free from weeds is about all that is necessary to produce a good crop under the conditions prevailing here. The result may have been different if the same experiment had been conducted in the arid West. It is only at rare intervals that the rainfall in Maryland is so slight that it is practicable or necessary to work for a 'dust mucch.' What is really important is to destroy the weeds and stir the soil fairly deep to aerate, and at the same time dry it and make it loose and friable."

In an essay by Dr. Chas. D. Woods of Orono, Maine, in the fifty sixth annual report of the Massachusetts State Board of Agriculture is the following: "All through the growing season the field should be kept free from weeds. The exaggerated ridge culture which is so common in Aroostook County could be better replaced in Massachusetts by a less pronounced ridge, or as level culture as is practicable. Suitable potato land is naturally or artificially so well drained that it does not suffer from excessive moisture, and with the high-ridge culture there is danger even in a moderately dry season of the crop suffering from lack of water. The frequent running of the cultivator not merely keeps down the weeds, but it lets the air into the soil and prevents excessive loss of moisture from evaporation, and in every way seems to be beneficial to the crop. This should be kept up until the vines pretty well cover the ground. If weeds are appearing in the drill, these should be removed by hand."

By the foregoing it will be seen that much depends on the individual, who must study his conditions and adapt practice accordingly.

Continue to: