Garden Design. Part 6

Description

This section is from the book "Design In Landscape Gardening", by Ralph Rodney Root, Charles Fabens Kelley. Also available from Amazon: Design in Landscape Gardening.

Garden Design. Part 6

Within the major limitations of formal and informal, architectural and horticultural emphasis, position and topography, there is considerable scope for the exercise of imagination by the garden-designer, although, where the gardens are designed for esthetic purposes, the taste of the client is a rather powerful determining factor. He may wish to make his garden naturalistic; that is, of a sort that he would find in a ramble about that locality, growing in natural conditions. He may wish to make it picturesque by emphasizing unusual features and combinations, or he may, from his interest in other countries, desire a large display of exotic plants. These questions deal not only with the plant material, but more or less with the arrangement. One cannot use the irregular plant material in formal planting schemes any more than one can produce an appearance of informality by the use of stiff, precise plants and clipped hedges.

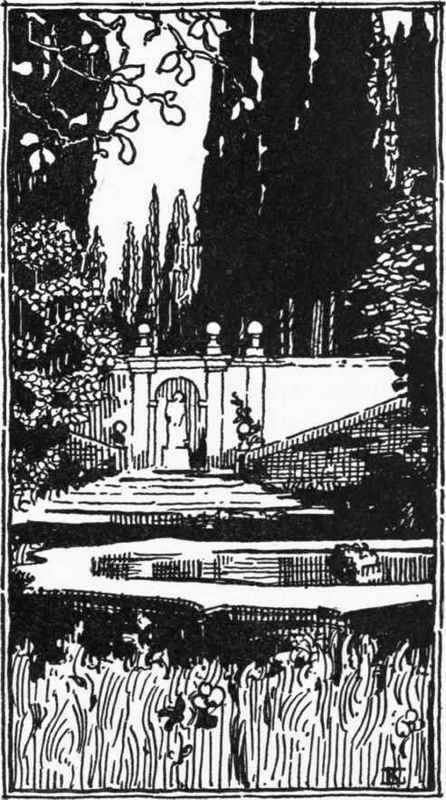

Figure 63. POMPEIAN FOUNTAIN HEAD.

Photograph by Anderson.

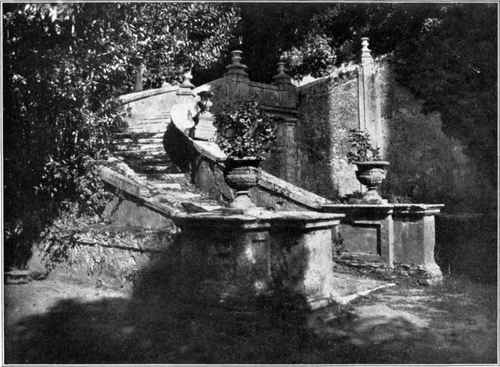

Figure 64. STAIRWAY AT THE VILLA D'ESTE.

The villa type of garden is one which must be considered most frequently in America, and is the type employed to best advantage in the suburbs of large cities, and in the residential portions of small cities. The garden planting in this case is considered as a setting for the house, and therefore spreads itself about more than if it were restricted to a definite area, as in the case of the out-door-room type of architectural garden. Neighborhood planting would come under this head. The out-door room idea may exist, indeed, as a part of the scheme of villa planting, yet the restriction of all plants to such a purpose would lay major emphasis on a strictly formal treatment, and would not help to tie the dwellings in with the more or less irregular surroundings of American suburbs.

Where views can be seen from the house, the planting of the villa garden should be such as to emphasize the prospect, and wherever any objectionable views occur they should be screened by a judicious use of shrubs. Where the grounds are of sufficient extent, games and recreations enter into the problem. The laying out of tennis-courts, bowling-greens, swimming-pools, and even tracks and base-ball diamonds must often be taken into consideration in connection with villa gardens. The landscaping of a villa is influenced largely by its scale, but it occurs as a sort of middle ground between the formal and the informal types, using sometimes the freedom of the one, and sometimes the restraint of the other.

Topiary work has long been associated with formal gardening, and would appear to be at variance with many types of planting, and altogether individualistic (see Fig. 58). Upon close study, one finds that, instead of being sharply differentiated, this type of planting is really a form of the gardenesque. Topiary was introduced into England by William of Orange and Queen Mary in the sixteenth century. It became a fashion among the wealthy class in England, and gradually spread, so that even at the present time it is common to see trees clipped in various forms in the gardens of the smaller homes.

Figure 65. RETAINING WALL AT VILLA FALCONIERI, FRASCATI, ITALY.

Topiary work may be divided into three types of planting: the parterre type, in which the planting is to be seen from one point; the formal type of planting, in which, though the plants are seen in elevation, they are used to bring out some particular feature in the design; and finally the type in which trees of different shapes and sizes are employed much the same as in gardenesque planting, where plant material is grouped and dotted about without regard to its composition in mass. The plants used for this work are those which are naturally formal or peculiar in shape; those which are restrained by clipping; and plants which have been made to grow dwarfed by clipping, budding, or by binding the roots.

Almost all garden design, then, can be analyzed as falling more or less under one of the two great divisions, the formal and the informal. The garden is a personal sort of thing, really the most intimate part of any landscape scheme, and if it does not reflect something of its owner, it falls short of its possibilities. It may be as small as one of the tiny cottage gardens of England or as large as the gardens at Versailles, but it is sure to conform to certain general principles, not rules. Stated simply, it may be said that every part of a garden must contribute toward the beauty of the general scheme, and that it will not do this if it seems to be present without a purpose. Every part of a garden should be esthetically utilitarian.

Continue to: