34. Combination Of Parts To Form A Whole

Description

This section is from the book "The Villa Gardener", by J. C. Loudon. Also available from Amazon: The Villa Gardener.

34. Combination Of Parts To Form A Whole

The rules, or rather, subordinate principles, derived from the principle of a whole are very numerous, both in architecture and landscape-gardening. In architecture, a building is generally considered as forming a whole of itself, without reference to the scenery with which it may be surrounded; but, in landscape-gardening, a building is only considered as forming a whole in combination with the scenery by which it is surrounded. Hence, as every whole must be composed of parts, a building in a town, to aspire to that character, cannot be so simple as it may be in the country, amidst verdant scenery. In the town, it ought, with a view to its effect as a whole, to be broken into parts, one of which should prevail in effect over the others, which ought to be subordinate to it, while they co-operated with it in forming a whole. Thus, two pavilions joined together, without a centre or main body, could not form a whole; but, with the main body larger than either pavilion, the whole produced would be acknowledged as such by every eye accustomed to look at objects otherwise than in detail. In the country, the plainest form of a house, a mere cube of masonry, may form a whole, if judiciously surrounded by trees.

These trees must, if planted near the house, be either considerably lower than the house is high; or, if the trees are of the same height as the house, there must not be more than one or two of them, or there must be so many as to render the trees the main feature of the whole, and the house only a subordinate feature. Wherever the house is surrounded, or even embraced, on three sides, with a mass of trees of the same height as itself, the view fails to produce the effect of a whole: no one object in the picture has the ascendency; and, if it were not for other counteracting associations, such as that of the wealth and dignity of the proprietor, and the comfort and splendour which are known to exist in and about such dwellings, the bare impression, as a landscape, would be disagreeable. On the other hand, when a house is surrounded, or embraced on three sides by a mass of wood, either a good deal lower than itself, or a good deal higher, a whole is produced, in which the character of architectural dignity prevails in the former case, and of sylvan dignity in the latter.

A square house in the country, in an open plain or pasture, unsurrounded by trees, or by other buildings, can never form a whole; because it has no object of any kind to group with it.

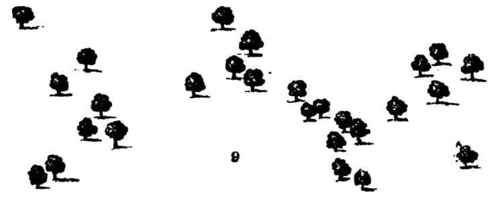

35. A house may form a whole by itself, without the addition of trees, and so may trees, without the addition of any other objects; but as, in that case, the house must be rendered independent of exterior objects by being broken into parts, so must the wood. In the one case, as in the other, one part must take the lead from one point of view; and all the other parts must obviously belong to it, and yet be subordinate. In the case of a park sprinkled over with trees, if these have been judiciously disposed, they will form a whole with almost every change of the position of the spectator; that is, those near the eye will group together, and form the principal mass; while those which are more distant will form subordinate masses, and unite in supporting the first For this purpose, the trees in the park most not be uniformly scattered oyer the surface, but planted in such a manner as to' exhibit connection and grouping, even in the ground plan. In fig. 8., the trees are too far apart, and at too uniform distances from one another, to group, or fall into expressive wholes; but in fig. 9., they will group agreeably with every change of the spectator.

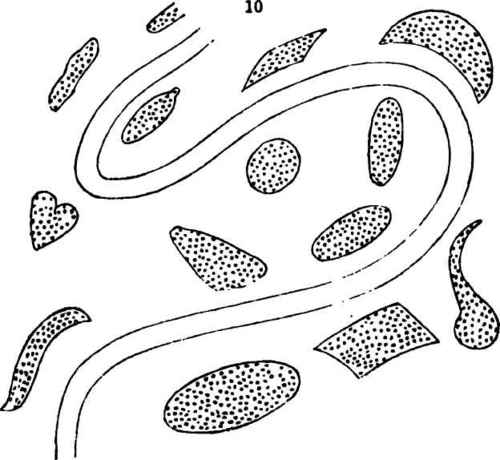

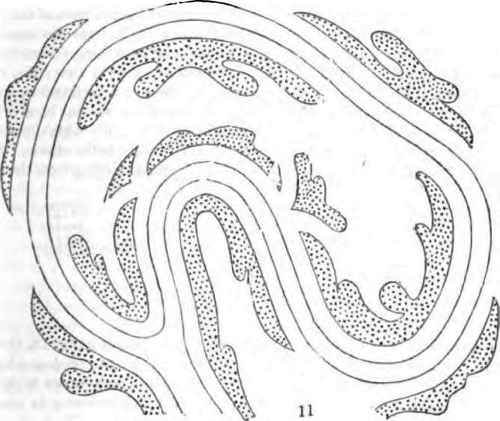

36. The expression, " a group of objects" merely implies that these objects form a whole. Nearly the same remarks will apply to a lawn varied by flower-beds, or by beds of low shrubs. The beds, if distributed uniformly over the lawn, will never group so as to satisfy the eye of a spectator who is either walking in it, or on a gravel walk round it The defect will be rendered obvious by comparing fig, 10. with fig. 11. The shapes of the former are unartiat-like, as well as too uniformly distributed over the surface; those of the latter are artist-like, and group or unite both with the turns of the walk, and with their reciprocal shapes.

37. Trees in a park may form a whole relatively to one another, and yet not relatively to the surface of the ground: for example, they may be placed on the levels only, and not on the hills; in which case, the hills will not group with the trees; and, when the height of these hills approaches nearly to that of the trees, the effect, both of the hills and trees, will be in a great measure, counteracted. On the other hand, by planting trees on the heights as well as on the plains, the views would present groups as effective as if the whole park had been a plain; and, if the hills were chiefly planted, their effect would be much more striking than anything that a plain could possibly produce. Even the magnitude which trees are calculated ultimately to attain, relatively to the extent of the surface on which they are to be planted, should be taken into consideration, no less than their magnitude relatively to that of the buildings which are near them. Thus, a small park would be injured in effect if planted with the highest and most bulky trees, because they would not form a whole with any object in it; and, though they might group together, and form a whole among themselves, yet that whole would be utterly disproportionate to every thing else in the park.

On the same principle, the apparent magnitude of water, relatively to the size of the park in which it is placed, may be diminished or increased according to the size of the trees planted near it. Perhaps one of the practices most adverse to the formation of a whole in planting trees is, to plant one part with very large trees, and another part, seen in the same view, and at the same distance from the eye, with small ones. Hence, group of aged treat among groups of shrubs do not unite so as to form a whole, without the introduction of trees of an intermediate size. In planting trees, even the kind of tree requires to be noticed, with reference to the production of a whole. An equal number of spiry-topped trees with round-headed ones in a group will not form a whole, from the incongruity of their forms; while a number of round-headed trees of the same bulk, and equidistant from the eye, will not form a whole, from the sameness of their forms and magnitude. Even in sloping and smoothing the surface of ground, the principle of a whole must constantly be kept in view; for, if all the curves and the slopes are of the same curvature and inclination, and of the same magnitude, they will not group; because there will not be a central or leading feature.

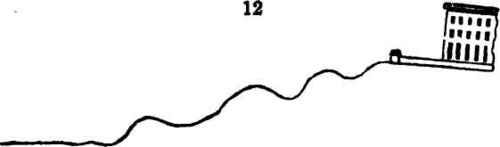

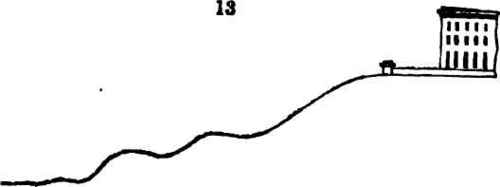

There must be a prevailing slope; one which takes the lead, either from its magnitude, or its position relatively to the others. Suppose figs. 12. and 13., to represent the sections of ground sloping from the front of a house, it will not be denied that there is more of effect in fig. 13. than in fig. 12.; and the reason is, that there is a feature in fig. 13., produced by the large slope which occupies the place of the two smaller undulations fig. 12. 38. In laying out and planting grounds, it is not only necessary to consider how trees may form a whole with buildings, with themselves, with shrubs, with ground, with water, with rocks, and even with fleeting objects, such as animals; but how they may form a whole with the objects at different seasons of the year. Thus, one part of the place must not be entirely planted with evergreens, and a corresponding part, which is seen at the same time, planted with deciduous trees. In looking down from the windows of a house, whether on an extensive park, or on a lawn of a few acres, it would be unsatisfactory, during winter, to see the principal masses of plantation, on the one hand, all, or even chiefly, evergreens, and, on the other, all, or chiefly, deciduous trees.

It would also be unsatisfactory to see evergreens equally mixed together throughout the view, instead of being bo distributed, and yet so connected, as, at a distance, to unite in forming one grand whole.

Continue to: