Chapter III. Ornamental Gardening

Description

This section is from the book "Handbook Of Hardy Trees, Shrubs, And Herbaceous Plants", by W. Botting Hemsley. Also available from Amazon: Handbook of hardy trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants.

Chapter III. Ornamental Gardening

It does not come within our province, nor within the limits of this volume, to enter into details and directions respecting the laying-out and construction of a garden. To treat landscape and architectural gardening in an exhaustive and instructive manner would alone fill a much larger book than the present, and require a far more extensive knowledge of the subject than we pretend to possess. Nevertheless, there are many questions relating to the working arrangements of a garden, whether large or small, which it will not be out of place to refer to here. Alterations and would-be improvements of an original design are frequently undertaken by young gardeners without any fixed or preconceived idea of the object in view, or any notion of the cardinal principles to be observed in carrying out these operations. Too often features are introduced in this way, wholly regardless of their suitability to surrounding objects and conditions. A tree or a shrub, or a group of trees or shrubs, is planted, a conservatory or rustic summer-house is built, an aquarium, rockery, or terrace is formed, a geometrical parterre is devised, or a number of vases or groups of statuary are set up, and probably great pains and expense bestowed upon each separate work in ordei to produce an effective display; but all to little purpose, on account of the disregard of the fundamental principle that each detail of a garden should be subservient to and in harmony with a definite plan, forming a complete picture or series of pictures. Gardening is a veritable art, and one whose varied details are not mastered without much application, power of thought, and natural taste. It is an art, too, that may be as effectively practised in the cottage garden or villa plot, as in the princely domain of hundreds or thousands of acres in extent. The only difference should be in size and corresponding magnificence; none in regard to merit as a design appropriate to the situation.

One of the gravest faults committed by inexperienced gardeners is the confusion of styles by indiscriminate planting, and tasteless use of architectural adjuncts. A large and diversified area may admit of the development of all the known resources of horticulture, both in the picturesque and formal styles, including the various purely artificial accessories. But in all cases a levish display of vases and other stone and rustic work should be avoided. It is much easier to err on the side of profuseness than on the side of sparseness of inanimate objects. We have seen this idea so much overdone as to give a small flower-garden the appearance of a manufacturer's show-yard. Where these accessories are admissible, or properly form a part of the plan, great discrimination and judgment should be exercised in the selection of elegant and suitable designs, harmonising as far as possible with the permanent buildings or other contiguous surroundings And, again, in the choice of a design for a pleasure-garden, whatever the size, due attention should be paid to the natural capabilities of the site, the style of the dwelling-house, and also to the character of the adjoining premises. In a broad sense, then, the plan should be projected for the ground, though to a certain extent, and in detail, the ground must be moulded in accordance with the plan. There is, of course, ample scope for individual taste, even when artistic rules are not ignored. And as every man is free to indulge his own particular fancies, more especially in all that appertains to his home pleasures, it would be idle to lay down hard and fast rules for his guidance. But there is a large class of men whose pursuits naturally prevent them from obtaining the necessary practical knowledge to enable them to select suitable shrubs and trees and decide upon the most attractive disposition of them, to produce a permanently effective garden. And often, too, it happens that they cannot afford to engage the services of a talented gardener. It is on behalf of amateurs, and what we may term the unprofessional gardeners, that the following and foregoing remarks are penned. The proprietors of extensive gardens and park-lands, as a rule, have competent men to direct their establishment, men of experience, who thoroughly understand their craft, and who could learn nothing from us. But it is so apparent to all observers that there is wide-spread want of correct taste, that a few words on this subject will not be superfluous.

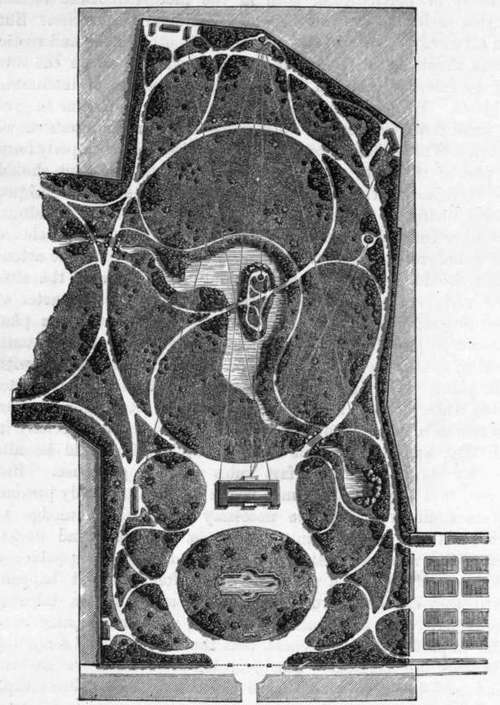

Some men seem to forget to make the appendages of their abodes really tasteful, because they are satisfied with the natural attractions of the surrounding country; and as for many of those who call themselves gardeners, it is not too much to say that they are utterly incapable of appreciating the beautiful. We shall not go into this subject to a wearying length, but rather confine ourselves to pointing out some of the shortcoming's of haphazard gardening, coupled with some indications for avoiding them. And here we may observe, that the picturesque style of gardening is purely English, and that all countries have professedly copied or imitated the English style, as it is termed, with such modifications as the exigencies of the country rendered imperative. When we come to speak of the flower-garden and small garden plots, further allusion will be made to this subject. In a large establishment we often find a blending of the various styles in separate portions set apart for their illustration. The primary thing to be considered is the selection and arrangement of the subjects for the arborescent and shrubby plantations, where the garden is large enough to admit of such, and scarcely any garden is so small but that it will afford space for a few shrubs. The accompanying plan, fig. 262, was designed by the able French landscape gardener, M. Barillet Deschamps, formerly director of the plantations of the city of Paris, and is inserted here to illustrate the disposition of the trees and plantations, so as to secure the best views the situation and natural features of the estate and the surrounding country will afford. It is intended to represent a landscape garden of small size, comprising from five to ten acres of land. It should be observed, however, that the same rules would hold good for a much larger garden, and consequently the plan may serve as a guide on a more extended scale. But to return to the disposition of the plantations. It seems almost superfluous to say that the planting should be done so as to preserve permanently the most extensive and varied views, having' at the same time an eye to necessary or desirable shelter for the residence, and to shut out all objectionable scenes, which will vary in nature according to the predilections of the owner. The lines on the plan, from the mansion to distant parts of the ground, will show what is meant by keeping the views open. It will be seen that the trees and shrubs are planted in detached groups at prominent points, nowhere intercepting the view, and leaving a clear space immediately around the house. And here we may remark that the planting of large-growing trees close to the house is, in our opinion, one of the greatest blemishes of modern villa-gardening. Pretty little residences are frequently completely shut in and darkened by large trees, and very often by one of the most objectionable of trees, namely, the Black Poplar. Trees close to a house may be all very well for a month or two in summer, but for the remainder of the year they make the house gloomy and damp, choke the gutters with dead leaves, and give the whole place an uncomfortable appearance. If the garden is not large enough to have large trees at a distance from the house, dispense with them altogether, or be content with one or two, or at Worst enjoy your neighbours'. There are scores of ornamental evergreen and deciduous shrubs to select from, and creepers against a wall do not keep a house so damp as overhanging trees.

Fig. 262. Plan Of Modern French Landscape Garden.

Continue to: