Part 58. Alcoholic Beverages

Description

This section is from the book "Plants And Their Uses - An Introduction To Botany", by Frederick Leroy Sargent. Also available from Amazon: Plants And Their Uses; An Introduction To Botany.

Part 58. Alcoholic Beverages

Part 58. Alcoholic beverages and stimulants in general. Alcoholic beverages are either fermented or distilled.

Fermented Beverages

Fermented beverages include beers or malt liquors, and wines. Beer, as already stated (sections 19 and 29), is made by fermenting a sweet liquid obtained chiefly from barley malt. In much the same way that the diastase in the sprouting grain changes the starch into sugar, an enzyme contained in the yeast which is added to the sweet malt liquid, changes its sugar into alcohol and the gas known as carbon dioxid. Yeast is a plant consisting of exceedingly minute bodies of the form shown in Fig. 151. These multiply very rapidly under favorable conditions of food supply and temperature. Hence a small amount of yeast added to a vat full of malt liquid soon becomes a considerable quantity. When the fermentation is well under way the liquid is put into air-tight kegs or bottles so that the gas produced may be retained. When the beer is poured out this gas rises to the surface and forms bubbles of foam. After the sugar is converted into alcohol and carbon dioxid gas, the alcohol may be turned into acetic acid (the acid of vinegar) by a plant similar to yeast (see Fig. 152) unless its action is prevented. This is accomplished mainly by the addition of hops (Fig. 153) which at the same time impart their peculiar flavor to the beer and give it a bitter taste. The preservative action as well as the flavor of the hops is due chiefly to a volatile oil of which the fruit contains about 1%. The stupefying effect of beer is also believed to be due in large part to the flavoring materials derived from the hops. Malt liquors contain about 4-10% of alcohol.

The process of fermentation may be observed readily by adding yeast to water sweetened with molasses and keeping the mixture for some hours in a warm place. Bubbles of carbon dioxid are given off abundantly and a faint smell of alcohol may be detected. If some of the fermenting mixture be boiled in a flask to kill the yeast, the neck of the flask being plugged with a wad of cotton wool (which will permit the access of only pure air to the mixture), the fermentation will be stopped and the liquid will keep indefinitely. The killing or exclusion of yeasts and similar agents of decomposition from foods to be preserved is the secret of the process of "canning" or "tinning" meats, vegetables, and fruits.

Wine is made by expressing the juice of grapes or other fruit and allowing yeast (which occurs naturally on the surface of the fruit) to produce alcoholic, fermentation of the sugar contained in the liquid. When this process has gone far enough the fermentation is stopped, generally by heating to kill the yeast and any vinegar ferment that may be present, and the wine is kept in tightly closed vessels to exclude the air and all ferments. By standing thus, wines develop with age minute amounts of certain flavoring substances, mostly volatile oils, or ethers upon which depends chiefly the value of the wine, and probably also to a considerable extent the diverse effects upon the human system of different wines of similar alcoholic strength. The proportion of alcohol in wines is about 10-25%. Strong wines have alcohol added after fermentation. Champagne is a wine containing a large amount of carbon dioxid gas.

Distilled Alcoholic Beverages

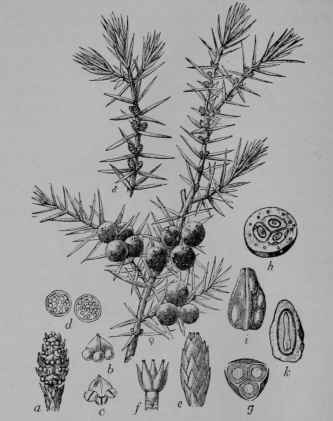

Distilled alcoholic beverages include spirituous liquors, such as brandy, rum, whisky, and gin; and liqueurs such as absinthe. Spirituous liquors contain about 40-60% of alcohol. Brandy is made by distilling wine. Rum is distilled from molasses. Whisky and gin are both distilled from a sort of beer made from grain, generally maize, rye, or wheat. Gin differs from whisky in being flavored with the volatile oil of juniper berries (Fig. 154) and other aromatics. These flavoring matters act powerfully upon the system, and make gin an especially dangerous liquor.

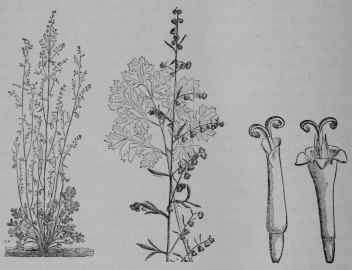

Liqueurs are sweetened spirituous liquors containing peculiar flavoring matters, usually volatile oils. In the case of absinthe the flavor is due chiefly to the volatile oil of wormwood (Fig. 155). This is a very powerful drug, which, in comparatively small amount, produces violent convulsions. Absinthe acts similarly and is justly regarded as the most pernicious of all alcoholic beverages.

All food-adjuncts, as we have seen, are taken with food primarily for their stimulating effect on the system. This effect is shown by more copious flow of the digestive juices, and by generally increased activity of the digestive organs. The very savor of food as we say "makes the mouth water." This is not because stimulating substances bring any considerable amount of energy into the body, but because they set free energy which the body has derived from nutritive substances and stored ready for use. Yet, since energy must be expended in digestion, a certain degree of stimulation may be helpful or even necessary. On the other hand, since the release of too much energy works harm, overstimulation is sure to prove injurious; and the danger of overstimulating is the greater from the fact that stimulation is pleasurable even when carried beyond the point of safety. This point of safety varies widely with different individuals, and in the same individual under different conditions of health and sickness, and at different ages. Stimulants, therefore, may be helpful or harmful according to the amount used and the bodily condition of the individual. Overstimulation is always followed by harmful reaction resulting in more or less exhaustion or derangement of the system which may lead to grave consequences, especially in the case of young people.

All food which has an agreeable flavor is more or less stimulating. In vegetable foods as we know the flavor naturally belonging to the plant or developed by heat is often strongly marked and characteristic, as, for example, in turnip, parsnip, celery, cucumber, muskmelon, pineapple, peanut, and pop-corn; and this flavor is due commonly to the presence of a volatile oil, the amount of which, however, is so small that overstimulation is not to be feared. On the contrary, the flavoring matter by its presence greatly helps the digestion of the nutritive substances in the food. These natural flavors of foods, as we may call them, are generally all that persons in good health require. Artificial flavors, as we may call the various aromatics added to food, may occasionally be used advantageously and with comparative safety to impart to insipid nutrients mild flavors similar to those of natural foods. Strongly stimulating beverages, however, such as tea, coffee, and alcoholic drinks are seldom necessary to health, and are often injurious to adults, while to young people they are frequently a source of lasting evils. The use of substances which act so powerfully on the nervous system should be regulated by the advice of one's physician.

The effect of artificial stimulants on the human body is much like that of a whip on a horse. We know it to be foolish and cruel to whip a colt, and it may ruin his chances of ever becoming a good horse. It is almost as foolish and may be dangerous to whip a willing horse, although a sluggish horse may need a touch of the whip occasionally to keep him up to his work; and emergencies sometimes arise when a horse must be vigorously whipped to obtain his utmost speed at any risk. So to a healthy child artificial stimulants other than the mildest are unquestionably pernicious; to a healthy adult they are unnecessary and generally harmful; to persons out of health, sometimes beneficial and sometimes injurious; while on rare occasions they are regarded by many physicians as a necessity for saving life. In such times of special need, however, stimulants are useful to a person only in so far as he has not previously by overuse deprived them of their power. It often happens that an intemperate person dies when a person who had always been temperate would be saved by the stimulant upon which the physician is depending.

Fig. 153.-Hops (Humulus Lupulus, Mulberry Family, Moracece). 1, branch bearing staminate flower-cluster. 2, branch bearing pistillate flower-clusters, and leaves. 3, pistillate flower-cluster. 4, two pistillate flowers and their bract. 5, ripe cone-like fruit-cluster. 6, a single fruit. (Wossidlo.)-A twining perennial herb with rough stems, growing 10 m. tall; leaves rough, hairy; flowers, greenish; fruit, straw-colored. Native home, Europe, Asia, and North America.

Fig. 154.-Juniper (Juniperus communis, Pine Family, Pinaceoe). Staminate flowering branch, 3/4. Pistillate fruiting branch, 3/4; a, staminate flower, enlarged; b, stamen, back view; c, same, lower view; d, two pollen grains; e, pistillate shoot; f, three ovules, and their scales, the front one bent down; g, same cut across; h, fruit, cut across, showing the three seeds in the aromatic pulp formed of the three scales grown together; i, seed, entire; k, same, cut lengthwise to show embryo and seed-food. (Berg and Schmidt.)-Shrub with spreading branches, or a tree growing about 12 m. tall; leaves spiny-pointed, whitish above; flowers yellowish; fruit dark blue with a bloom. Native home, north temperate regions.

Fig. 155.-Wormwood (Artemisia Absinthium, Sunflower Family, Compositce). Plant in flower. Leaf and flower-clusters. Outer floret, 7/1, Inner floret, 7/1. (Baillon.)-A perennial herb, about 1 m. tall; leaves white-silky; flowers greenish; fruit grayish. Native home, Europe.

Continue to: