Cerebral Hemispheres

Description

This section is from the book "A Manual Of Physiology", by Gerald F. Yeo. Also available from Amazon: Manual Of Physiology.

Cerebral Hemispheres

It is now universally regarded as a recognized fact that the hemispheres of the brain are the seat of the mental faculties perception, memory, thought and volition. The cerebral cortex is the part of the nervous system in which the subjective perception of the various sensory impulses takes place, and in which impulses are converted into impressions or mental operations. It is in the cortical nerve cells that the so-called voluntary impulses, causing movement of the skeletal muscles, have their origin. It is thus a sensory and a motor organ. But it has a far wider range of function than is expressed by saying it is both sensory and motor. Thus restricted, its function would be no higher than that of the nerve centres in the spinal cord, etc. The cells of the cortex of the brain seem to differ from those of the lower nerve centres, which can only receive, and at once send out corresponding impulses, in this: when an impulse arrives at certain cerebral cells, it there excites a change, which, besides producing an immediate effect, leaves a more or less permanent impression. The impression persisting, if the cell be well- supplied with chemical energy in the shape of nutriment, it may be reproduced at a subsequent period. This revival of impressions, the effects of past stimulations, or "recollection," is exclusively the property of the cerebral cortex, and to it the hemispheres owe their mental faculties. During our lifetime sensory impulses are continually streaming into the cells of the cortex of the brain from the peripheral sensory organs. Thus innumerable impressions are stored up in. the nerve cells. The effect of the continuing presence of these impressions in the active cells is memory, and by association, arrangement or analysis of these persisting impressions, the activity of the cells gives rise to thought or ideation.

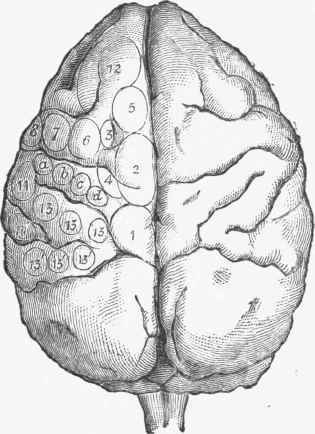

Fig. 258. Upper surface of the hemispheres of monkey, showing details of motor areas. References as in next figure. (Ferrier}.

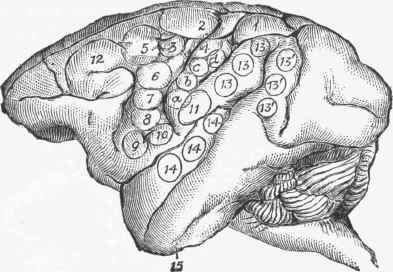

Fig. 259. Left hemisphere of monkey, showing details of motor areas indicated by the movements following stimulation of:

1. Superior parietal lobule; exciting advance of the hind limb.

2. Top of ascending frontal and parietal convolutions; flexion and outward rotation of thigh; flexion of toes.

3. On ascending frontal convolution near semi-lunar sulcus; movements of hind limb, tail and extremity of trunk.

4. On adjacent margins of ascending frontal and parietal convolution; adduction and extension of arm, pronation of hand.

5. Top of ascending frontal near superior frontal convolution; forward extension of arm.

a, b, c, d, On ascending parietal; movements of various muscles of the fore-arm.

6. Ascending frontal convolution; flexion of fore-arm and supination of hand which is brought toward mouth.

7. Retraction and elevation of corner of mouth.

8. Elevation of nose and lip.

9 and 10. Opening mouth and motions of tongue.

11. Retraction of angle of mouth.

12. Middle and superior frontal convolutions; movements of head and eyelids.

13 and 13'. Anterior and posterior limbs of angular gyrus; movements of eyeballs.

14. Superior temporo-sphenoidal convolution, ear pricked and head moved.

15. Movement of lip and nostril. (Ferrier).

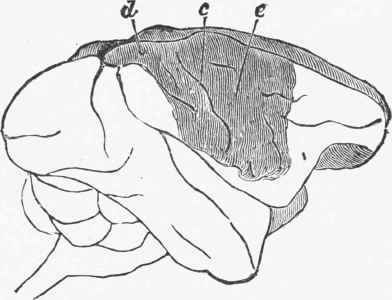

Fig. 260. Dark shading indicates the extent of a lesion of the gray matter of the right hemisphere of a monkey followed by complete motor paralysis of the limbs of the opposite side without impairment of sensation. (Ferrier).

c, Fissure of Rolando; d, Postero-parietal lobule; e, Ascending frontal convolution.

In close relation and connection with these cells of the cortex, in which permanent impressions are stored and ideation is accomplished, are those other groups of cells which have been mentioned as being in direct communication with the spinal motor centres, and can by the medium of the latter execute voluntary movement.

It is a very remarkable fact, that one side of the brain is sufficient for the perfect performance of the mental faculties. Memory, consciousness and thought can all be operative in a perfectly normal way, when one side of the brain is rendered incapable of performing its functions by disease or injury.

This is not the case as regards sensory impressions, or voluntary movement, both of which are destroyed on the side of the body opposite to that of the injured hemisphere. The difference between the mental powers and mere motor and sensory functions of the brain can be seen in those cases of paralysis known as hemiplegia. The patient is frequently fully conscious, and may possess unimpaired powers of thought and memory, yet he is unable to perceive the sensory impulses coming from one side of his body, or to send voluntary impulses to the muscles of the paralyzed side.

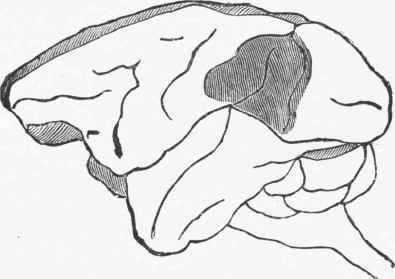

Fig. 261. The dark shading shows the region of the angular gyrus of a monkey, injury of which is followed by transient blindness. (Ferrier).

The cells which act as the immediate receivers of afferent, and dispensers of efferent impulses, to one or other side of the body, are then localized to one hemisphere, viz., that of the opposite side, while mental operations are diffused over the cortex of both hemispheres.

Continue to: