Lavatories

Description

This section is from the book "Modern Plumbing Illustrated", by R. M. Starbuck. Also available from Amazon: Modern Plumbing Illustrated.

Lavatories

Lavatories are generally made of marble, enameled cast iron, or porcelain.

Marble is fast being superseded by enameled cast iron and porcelain. Marble lavatories present opportunity for the collection of filth in the joints and corners between the marble parts and between the bowl and the marble.

Enameled cast-iron and porcelain lavatories are cast in one piece, which includes both the back and the bowl, for which reason there is no necessity of setting the bowl, and therefore no possibility that it may become loose and need resetting, as often happens in the use of marble lavatories.

Plate II. Lavatories

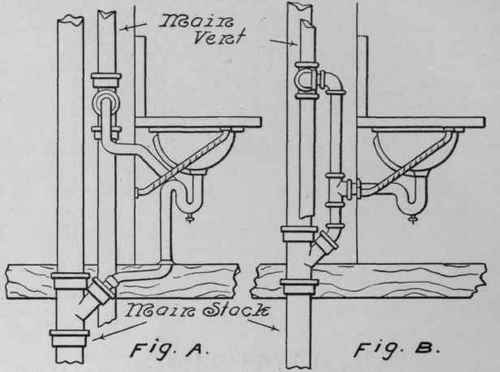

Plate 2. Connections for Lavatory

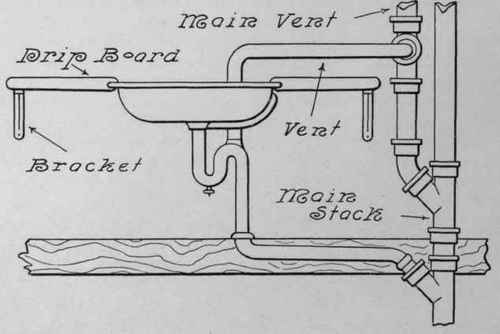

Connections for Pantry Sink.

Being cast in one piece, there are no joints to fill up with filth. It is for these reasons that enameled cast-iron and porcelain lavatories are preferable to marble.

The waste from the lavatory is generally of 1 1/4-inch pipe, but should never be as small as I inch, a size which is sometimes used. The trap vent should also be 1 1/4 inches in size. The lavatory should be set so that its upper surface is about 31 inches from the floor. The height may, of course, be varied to suit the desires of the owner.

The trap of this fixture is very liable to stoppage, not from greasy matter as in the trap of the kitchen sink, but from soap, lint, and hair.

Two methods of making waste connections for the lavatory may be followed, shown in Plate 2 by Figs. A and B. The waste may be carried to the floor, as in Fig. A, or directly back to the wall, as in Fig. B. The latter method is preferable, as the waste connection so made is shorter, there is less of the work exposed to rough usage, and a separate entrance into the main soil or waste pipe may always be secured. The vent of the half S-trap may be taken off farther from the seal than in the case of the full S-trap, resulting in a lower rate of evaporation, and the half S-trap is less subject to siphonage than the full S-trap, owing to the long outlet arm of the latter. Usually when the half S-trap can be used for the lavatory, or, in fact, for any other fixture, the continuous method of venting may be applied, as shown in Fig. B. This method is of great advantage to any fixture, and is fully described under Plate 26.

An objection to the use of the patent overflow bowl, such as shown in Figs. A and B, is that the overflow soon becomes coated with filth, which often throws off foul odors into the room. The use of scented soaps increases this objectionable feature.

The same thing occurs in public toilet rooms when a line of several lavatories is served by a single trap at the end of the line. This long line of fouled waste pipe sends out its foul odors into the room through the outlet of each bowl.

Italian and Tennessee marble is the material mostly used for marble lavatories.

On good work, lavatory top slabs are countersunk, with moulded edges, and 1 1/4 inch thick. The backs and ends for lavatories may be 8, 10, 12, 14, 18, or 20 inches in height.

The standard sizes of marble slabs for lavatories are 19 X 24, 20 X 24, 20 X 26, 20 X 28, 20 X 30, 22 X 28, 22 X 30, and 22 X 36.

On the better grades of work the larger sizes of slabs, with high backs, are mostly used.

Lavatory bowls may be obtained either round or oval, with common overflow or patent overflow. Round bowls are made of 12, 13, 14, 15, and 16 inch diameter, the 14-inch bowl being largely used on general work.

The sizes of oval bowls are 14 X 17, 15 X 19, and 16 X 21.

The bowl is generally fastened to the marble slab before the latter is set in position. The bowl is attached by means of bowl clamps. Three or four bowl clamps may be used on round bowls, but not less than four on oval bowls.

The slab is drilled out to receive the clamp bolt, the hole being cut under at the bottom. The bolt is held firmly in the marble slab by means of lead poured in around it and caulked, the under cut at the bottom clinching the lead and preventing it pulling out. The joint between the bowl and the marble is made with plaster-of-paris.

In connection with the subject of marble work, the making of marble cements may be of interest. Portland cement withstands water, as also a cement made by soaking plaster-of-paris in a saturated solution of alum, the mixture being baked and ground into a powder and applied by mixing with water. A putty made of litharge and glycerine is also good.

Continue to: