Chapter XVI. Halls: Apartments

Description

This section is from the book "Homes And Their Decoration", by Lillie Hamilton French. Also available from Amazon: Homes and their decoration.

Chapter XVI. Halls: Apartments

THERE are two kinds of halls which we in this day are called upon to consider. The architect designs one; the builder constructs the other.

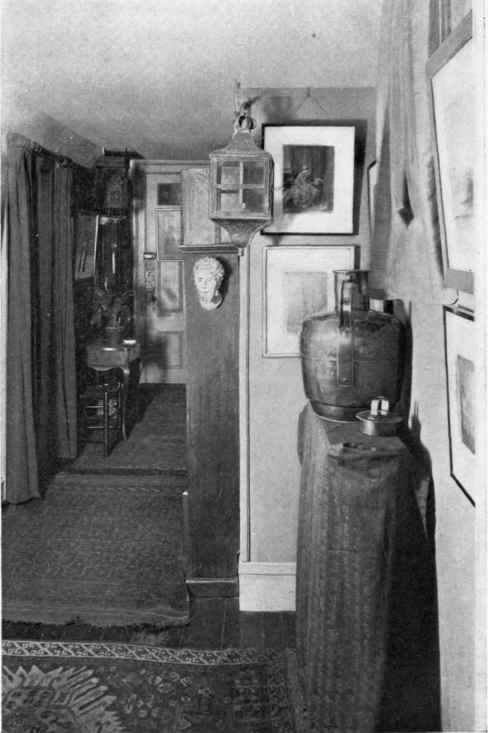

When a hall is to be treated we must know whether it is a harmonious composition, or whether it is an ugly passageway to be beautified if possible; but the problem of its decoration can never be solved until certain questions are answered. Where does the hall run from, and where does it lead? Is it only the bare passage-way of an ordinary house in town, the stairs facing the front door? Or is it the hall of an apartment, without windows, and having no steps? Does it open on a village street or on well-kept lawns? Has it a pleasant vista? What rooms open from it? Or, has the purpose of its owner been to make it a lounging place for his friends and his family? If this has been his object, has he provided his house with other passage-ways and entrances, protecting the inmates of the hall from the casual visitor in town, and from the pedler in a country place?

The subject is one of no little importance. Like his speech, a man's hall betrays his place in life, and you see it the moment that his front door is opened. It stamps him as does his greeting. A man who does not know how to address a stranger, who is ungrammatical and awkward, cannot pretend to you that he has been born and bred among those who have been accustomed to the world, and that at another time he will prove it to you. His first words have already convinced you, and no elaborately prepared after-speeches will better his case. He whose hall is vulgar with inappropriate belongings, made pretentious by mere display, or in which the stranger is too quickly admitted into the intimacies of family life, cannot be more successful in persuading you that the rest of his house is as it should be, or that the secret of polite living is his.

When a woman can design her own hall as a medium of expression for herself, she is to be counted happy. The majority of us must content ourselves with those which the builder has erected for our particular pain and discomfiture. And of all those with which he has afflicted us, certainly there is none quite so hopeless as that found in an every-day apartment, a passage-way so ugly that it has been made the subject of endless newspaper pleasantries.

In Mr. Howells's "A Hazard of New Fortunes,"

"THE MAJORITY OF US MUST CONTENT OURSELVES WITH THOSE WHICH THE BUILDER HAS ERECTED".

Mrs. March, tired out with trying to find a pretty-apartment in New York, dreams at night of "a hideous thing with two square eyes and a series of sections growing darker, then lighter, till the tail of the monstrous articulate was quite luminous again." The every-day flat almost always has the light parlor in the front, and the light kitchen or bedroom in the back, the rest, as Mr. Howells describes it, "crooked and cornered backward through increasing, then decreasing, darkness." This is the apartment advertised as "seven rooms and a bath," and the hall, which is seldom more than three feet wide, is the twisted spinal column, as it were, holding the "monstrous articulate" together.

In apartments which rent for sixteen and eighteen hundred dollars a year, the builder now and then has shown some ingenuity in introducing a small vestibule just inside the front door, but even in that case he has been forced to make a long passage-way of the hall leading past the bedrooms. In a few instances only has he been clever enough to so arrange his hall space that when the front door is opened, a pretty vista is seen leading into one or more rooms at the end. It is not until the seven or eight thousand dollars a year apartment is reached that the hall becomes large enough for any architectural effects, for wide marble steps, columns, and balconies.

Like everything else in a small apartment, a hall should be treated with care and thought. This is imperative, not only because its configuration is apt to be bad, but because it forms the one general passage-way on which the parlor, dining-room, and bedrooms open. You must go through it to reach your kitchen and bathroom, and each of your visitors must be ushered into the parlor by way of it.

Because of these visitors, then, your hall, if you live in an apartment, must suggest no compromises, betray no careless intrusions from the bedroom or the storeroom. It must never look like the hall on the bedroom floor of a house. Although you may line it with books, and treat it with a certain informality, you can never regard it except as a passage-way, always ready for the reception of the most punctilious of your guests.

A hall begins with the front door. It is to be studied first from this point. Properly speaking, there should be just inside the entrance a table, a seat, a tray for cards, a pencil and pad, and a place for men's overcoats. The comfort and convenience of every arrival should be studied. The messenger boy should have a seat while he waits; so should the old lady who stops to have her overshoes removed. But an apartment seldom boasts sufficient space for the necessary comforts. The front door will sometimes open directly on a blank wall, and must be closed again, the visitor safe inside, before either the maid or the guest can move in a given direction. Nothing is so awkward, and, unhappily, nothing is more general.

When there is not sufficient space for the chair inside, one should be placed on the stair-landing outside, for the benefit of the breathless visitor who may have had to puff a way up three or four flights of stairs. On the blank wall opposite the door, a mirror would seem better than a picture. It would prove the most flattering of tributes to the excellence of one's guests. Looking-glasses make the vainest of men and women feel at home at once.

Continue to: