Chapter I. The Development Of The Chest And Standing Cupboard

Description

This section is from the book "Early English Furniture & Woodwork", by Herbert Cescinsky, Ernest. R. Gribble. Also available from Amazon: Early English Furniture & Woodwork.

Chapter I. The Development Of The Chest And Standing Cupboard

The chest or coffer was a most important article of furniture, especially during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, both in houses and monastic establishments. Some idea has already been given of the wealth, in carved and decorated woodwork, which must have been general even in small parish churches, until the first quarter of the sixteenth century. Enough has persisted to our day to give some vague idea of the amount and richness which must have been stored in these churches throughout the length and breadth of England. What has not survived are the treasures in the way of vestments, altar-cloths, jewels and ornaments of gold, silver and enamel, in chalice, paten, altar candlesticks and the like, as these were the prey of the despoiler long ago. Many accounts have been preserved of the wholesale destruction by fire of copes, vestments, banners and altar-cloths. There were many edicts, not only permitting, but even authorising and commanding the burning of canonical vestments as idolatrous trappings. In 1551 the order to demolish all high altars, and to substitute plain wooden tables, went forth, and was generally obeyed.1 Parish registers give innumerable accounts of the insensate destruction which was carried on from the middle of the sixteenth century, at intervals, until almost the end of the seventeenth. The spoliation of portable church wealth became almost a profession !

The safe custody of these rare fabrics, jewels and vessels of gold and silver, demanded the chest, and the greatest care was taken in its making, especially in the selection of the wood. The huchers or huchiers, who were employed in the manufacture, were a class of workmen of lower grade than the makers of purely architectural woodwork, but they were under the direct control of the Master Guild, the officials of which enacted stringent laws regarding the selection and seasoning of the timber. In the smaller churches, however, oak was not always used, deal being substituted, which, although an inferior wood, was more highly esteemed than oak, in panellings, from the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries, deal-panelled rooms being referred to in inventories, whereas wainscotting of oak is rarely mentioned.

1 This explains the presence of so many late sixteenth and early seventeenth-century tables to be found acting as altars, especially in country churches.

The earliest chests of which we have any knowledge date from the middle thirteenth century. The tops nearly always open on pin-hinges, that is, on two pins fixed at the ends of the back under-clamp of the top and socketed into the uprights of the sides. These are rarely, if ever, found in the fourteenth century, heavy iron clamp-hinges being substituted. Fig. 1 is the thirteenth-century type of chest, from Great Bedwyn Church, Wiltshire. It is roughly constructed, yet in a characteristically thirteenth-century manner. The front is a solid board of oak of great width, roughly finished with the saw marks left in its surface, tenoned into heavy uprights. These project over the ends and are united from front to back by two heavy cross pieces, the tenons of which are carried through to the front. The lower one supports the bottom of the chest, which is made from stout wood to carry heavy weights. The ends are housed into the heavy styles, and are fixed to the cross-pieces. There is no attempt at ornamentation, although, originally, the bottom of the upright styles may have been carved with simple cusping. The ironwork at present on the chest is all of much later date.

Fig. 1. Oak Chest With Deal Top From Great Bedwyn Church, Wiltshire. - 4 ft. 2 ins. wide by 2 ft. 1 in. high by I ft. 9 ins. from back to front. Early thirteenth century.

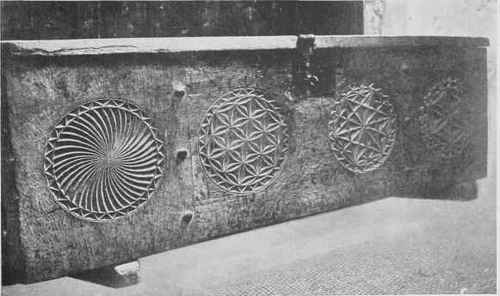

The next type, Fig. 2, which also belongs to the thirteenth century, is where the front is formed with very wide upright styles fixed flush to the centre and acting as huge clamps. The tenons of the central panel are secured in the mortises of these vertical clamps by large wooden pegs, which are here allowed to project, and are finished off as ornamental features. The entire front is fixed to the sides with heavy wrought-iron nails. This chest is rare, for its date, in being ornamented with roundels and geometrical devices in chip-carving. As a rule, thirteenth-century chests are plain, and tracery was never applied. This Earl Stonham chest is supported on large runners, kept well away from the ends to minimise any tendency to sagging of the bottom.

There is a still earlier type of chest than those illustrated here, which shows the woodworker copying the methods of the stonemason. This is the dug-out kind, of which several examples exist, where the chest is hollowed out and fashioned from one great piece of timber. Very few have survived, nor is this method calculated to produce a chest which is likely to remain for many years without falling to pieces, owing to the cracking and warping of the timber, which in this large scantling could not possibly have been seasoned before using. Where the reference occurs in the parish accounts of the thirteenth or fourteenth centuries to " item, 1 Great Old Ark," it is usually one of these dug-out chests which is described. Unfortunately, all chests of this type are not thirteenth century; the practice was still followed for nearly two centuries afterwards, and as the later copies are usually devoid of ornament of any kind, it is impossible to date them with any accuracy. Fig. 3 from Groton and Fig. 4 from Chelsworth are of this ark form, but are constructed chests. The way in which both are heavily banded with iron suggests that they were intended to contain articles of valuable and precious nature. The tops, in each case, are hewn from the solid trunk. Both of these chests are from poplar, a soft wood which is now much perished.

Fig. 2. Oak Chest. Earl Stonham Church, Suffolk. - Late thirteenth century

Continue to: