English Lacquer Work. Part 2

Description

This section is from the book "Early English Furniture & Woodwork", by Herbert Cescinsky, Ernest. R. Gribble. Also available from Amazon: Early English Furniture & Woodwork.

English Lacquer Work. Part 2

There are several conditions which render the Eastern lacquer not only superior, but also impossible of imitation by any methods of the West. The lac itself is an exudation of a native tree (Tsi),1 Rhus vernicifera or Rhus succedanea, - both varieties of the Sumach, - which when fresh, can be thinned down to any consistency, but when exposed to the air, hardens and cannot then be attacked by any solvents which we possess, even one so drastic as spirit-of-wine. This property of permanently hardening on exposure to the air renders the export of the raw Chinese lac nearly an impossibility.

In Japan the Urushi tree, from the fruit of which vegetable wax is derived.

Fig. 503. Japanese Cabinet In Black Lacquer. - Raised gold decoration. Mounted on carved and gilt stand of English make. - Mid-eighteenth century. Herbert Cescinsky, Esq.

Fig. 504. Cabinet Of English Lacquer On Carved And Silvered Stand. - Date about 1670-80. Victoria and Albert Museum.

Climate plays an important part in the successful application of the lacquer itself. Cold winds, or humidity of the atmosphere, will cause the varnish to chill and lose its transparency (it will be remarked that even in a finely prepared and finished coach panel, where as many as twenty coats of varnish have been used, there is never any real depth in the colour itself), and stoving or working in a heated room makes the avoidance of tiny air bubbles almost an impossibility. Modern European lacquer (so called) where a fine even finish has been produced, is nearly always shellac dissolved in spirit-of-wine, applied with the rubber instead of the brush, on a black or coloured ground, or, in other words, what is generally known as " French polishing." It lacks the hard brightness of varnish (difficult to explain, but quite unmistakable to one whose eye has been trained to observe the two) and has nothing of its elasticity. A polish finish is always " short," - to use the decorator's term, - and liable to crack or craze, especially when applied on a slow-drying painted ground which is always slightly expanding or contracting with variations of temperature.

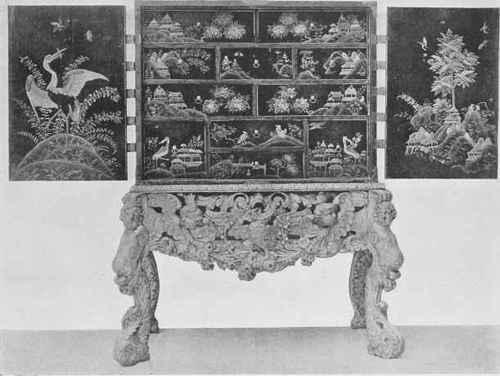

Fig. 505. The Cabinet, Fig. 504, Shown Open.

Lacquer, therefore, which has been coated on in a hot climate, commences with an initial advantage. The preservative qualities of the Chinese or Japanese lac are extraordinary. Large pieces, such as screen panels, are made from soft wood, often in two or more pieces jointed together with small square-sectioned dowels, but without the use of any adhesive, yet finished with these fine lacquered grounds they defy our Western extremes of climate for centuries, if the surface of the lac be unbroken. Stripped of this coating, these large screens would fall to pieces, or would warp or split, in a few weeks.

If the Chinese lacquer, especially that of early Manchu period (K'hang H'si, 1661-1721) or of the late Ming dynasty, is remarkable for its artistic spirit, that of Japan, especially of the late seventeenth century, is equally notable for its sheer perfection of finish. Grounded on the Chinese art, as much of that of Japan undoubtedly was, the Japanese, not only as imitators, but even as creators, often excelled their Chinese teachers. It is customary to despise much of this work, especially in collecting circles, and to stigmatise it contemptuously, as " Japanese," forgetting that the actual artistic conceptions, and especially the careful workmanship and skill displayed, even in the case of commercial pieces, are truly extraordinary. With signed pieces, made for Japanese notables, the high quality of the lacquered grounds is remarkable. In tiny sake cups the perfection of finish is incomprehensible to the European. There is no sign anywhere of contact before the lacquer was dry; it is as if these small bowls were prepared while invisibly suspended in the air.

Figs. 500 and 501 show the front and back views of one of these fine red ground sake cups of high grade Japanese work, measuring 3 3/8 ins. in diameter, the illustrations being, therefore, slightly reduced from actual size. In the centre of the back is the signature; and all the rims and edges show no sign of contact while in the process of drying. Fig. 501 is another of these bowls, fractured at an angle to show how thin and even this covering lacquer is.

Pieces of Oriental lacquer, usually small objects, were imported into England by the agency of the Dutch East India Company or the republican trading cities of Northern Italy, during the Tudor period, and in the reign of Charles I "Jappan" cabinets are referred to in inventories and, evidently, highly esteemed. The well-known square cabinets, on carved gilt stands, with doors ornamented with elaborate hinges and flat lock-plates, lacquered and decorated on both sides, and with a nest of drawers behind, were usually imported from 1650 to about 1670, after which date they were copied, with modifications, by the artisans in this country. The English lac, however, differs very materially from the Oriental, not only in execution but also in method, the grounds being prepared, as a rule, in varnishes, - from the resinous coccus lacca, - instead of the Chinese and Japanese insoluble Tsi.

Fig. 506. Cabinet Of English Black Lacquer On Carved Gilt Stand. - 6 ft. high by 4 ft. wide Date about 1690. - Lord Willoughby de Broke.

Fig. 507. Cabinet Of English Black Lacquer On Carved Gilt Stand. - 7 ft. 4 ins. high by 3 ft. 3 ins. wide by I ft. 7 ins. deep. - Date about 1700. Messrs. Gill and Reigate.

Fig. 508. The Cabinet, Fig. 507, Shown Open.

Continue to: