English Lacquer Work. Part 4

Description

This section is from the book "Early English Furniture & Woodwork", by Herbert Cescinsky, Ernest. R. Gribble. Also available from Amazon: Early English Furniture & Woodwork.

English Lacquer Work. Part 4

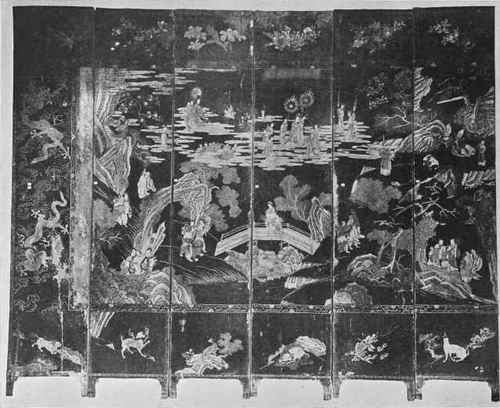

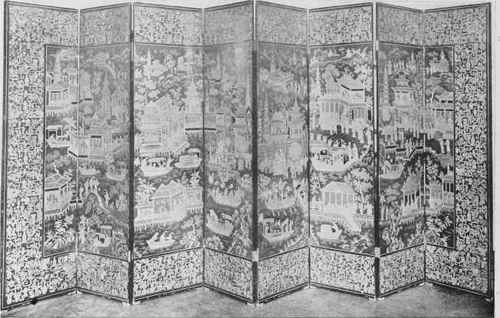

Fig. 510. Twelve-Fold Chinese Screen (One Half). - Incised, polychrome and sanded ornament on a semi-transparent ground of brown lacquer. - Dated, on reverse, 1671. J. Herrmann, Esq.

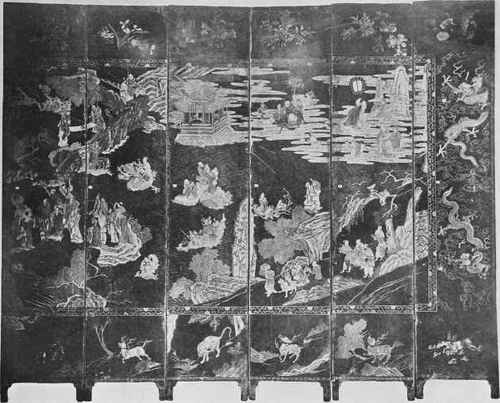

Fig. 511. The Other Half Of The Chinese Screen, Fig. 510.

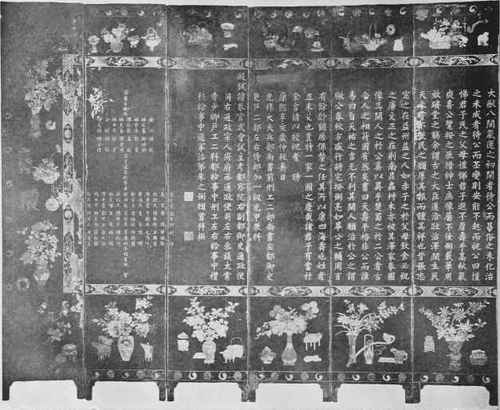

Fig. 512. One Half Of The Reverse Side Of The Screen, Figs. 510 And 511. - The date 1671, and the names of the donors are recorded here.

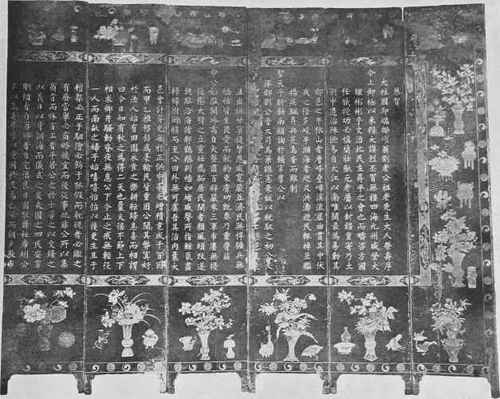

The early Manchu work can be best studied in the large Chinese screens which were imported into this country in the early eighteenth century, and which were, formerly, far more plentiful, some twenty or thirty years ago, than is the case at the present daY. In Figs. 510 to 513 one of these, of magnificent quality and exceptional interest, is illustrated. The ornament is incised in the lacquer itself, decorated in polychrome on a sanded ground, and with the exception of the heavy vermilion, the original colours are almost intact. The groundwork is a thick, semi-transparent brown lacquer glazed over a grey ground. The wood is a soft pine, each fold in two sections, dowelled together without adhesive, and preserved only by the air-excluding properties of the lacquer. On the reverse side, shown in Figs. 512 and 513, is a long inscription, in flowery Chinese, recording the fact that the screen was presented, in 1671 (the second year of K'hang-h'si) to a Chinese professor by his pupils, whose names are set out on the extreme left of Fig. 512. Each fold is joined to its fellow by primitive pin-hinges, two to each panel, which can be seen in Fig. 511. This is the Chinese method, the fixed hinge with a closed and riveted knuckle being entirely a Western idea.

Fig. 513. The Other Half Of The Reverse Side Of The Screen, Figs. 510 And 511.

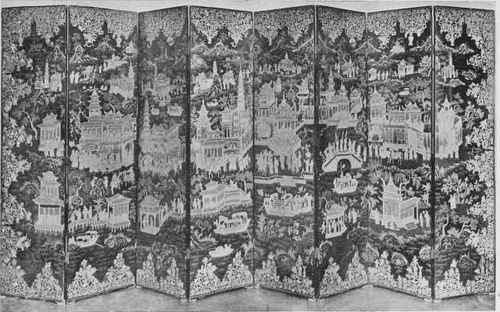

Many of these Chinese screens, especially those of the later eighteenth century, while possessing very little of the freedom and vivid draughtsmanship of the early Manchu work, and especially of the later Ming, almost atone by their careful detail and magnificent craftsmanship. Figs. 514 and 515 illustrate one of these, and it will be seen that one side is as lavishly decorated as the other. There is, practically, no reverse side, and the intricacy of the whole design is amazing.

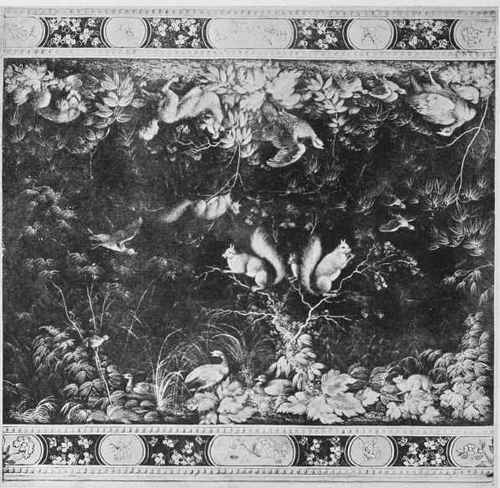

While in perfection of finish and detail of drawing, much of this Chinese work, and even that of Japan, is unapproached by any efforts of Western artists, occasional examples can be found which are much in advance of the usual lacquer of the time, and here the hands of Dutch or Flemish artists are strongly indicated. One of these is a table plateau, in four sections, from the collection of Lord Leverhulme, shown here in Figs. 516 and 517. The detail is in brown on a black ground, the work of amazing quality, with foliage and figures of birds and squirrels executed with a fineness of detail worthy of Gerard Douw at his best. The border is formal, consisting of long and short panels decorated with tinsel colours. The rims and the small claw-and-ball feet are of silver. The work is, approximately, of mid-eighteenth-century date, but its nationality is debatable.

Fig. 514. Eightfold Chinese Screen (Front View). - Late eighteenth century. C. H. F. Kinderman, Esq.

The rage, just prior to the publication of Chippendale's "Director" in 1754, was for the " Chinese Taste," as it was styled. The finest examples of this period, that is, exhibiting the greatest fidelity to the Chinese originals, are to be found in the glass pictures, not those where a print has been transferred to the glass and the paper carefully rubbed away (which should be despised by any true collector), but where the picture is actually painted on the glass from behind. Many of these, such as Fig. 518, have considerable merit and a value quite distinct from their rarity. So fine are the best of them, in execution, that they are frequently mistaken for actual Oriental work, although to one acquainted with Chinese forms and conventions their European origin should be, at once, apparent. In lacquered frames, of half-round section, with a small gilt fillet or hollow dividing the frame from the glass, they make extremely effective pictures, especially in a low deal-panelled Georgian room.

Fig. 515. The Reverse Of The Chinese Screen, Fig. 514.

Fig. 516. Table Plateau, In Brown Decoration On A Black Lacquer Ground. - Mounted with silver rims and feet. - Date about 1750. The Rt. Hon. Lord Leverhulme.

Fig. 517. A Section Of The Table Plateau Shown Above.

In considering these imitations of the Chinese, either in drawing or technical excellence, we have diverged somewhat from the progression of English lacquer-work, although there is little, if any, of the order which can be traced as in other furniture, English in inspiration as well as origin. With the square cabinets from 1670 to about 1720 there is little indication of date beyond the details of the stands themselves. Thus we can place the charming green lac cabinet shown in Fig. 519 at about 1690 by this detail alone. The ornament is good and well executed, on a ground of apple green, and the stand has the C-scrolled legs and flat stretcher which we associate with the reign of William III. This cabinet had rather an adventurous history. Bought in Sussex, it was dispatched to America, where in the extremes of climate of the Eastern States it would, probably, have been doomed in a few years. It remained in America, however, only a few hours. It was purchased almost as soon as it arrived, sent back to England, and now adorns one of the drawing-rooms in Dudley House, Sir John Ward's mansion in Park Lane.

Continue to: