Wood Panellings And Mantels. Part 17

Description

This section is from the book "Early English Furniture & Woodwork", by Herbert Cescinsky, Ernest. R. Gribble. Also available from Amazon: Early English Furniture & Woodwork.

Wood Panellings And Mantels. Part 17

The Renaissance in England appears to develop on coarser and cruder lines in the counties of the Western Midlands, beginning as far south as Gloucestershire and terminating with Lancashire. Cumberland and Westmoreland do not seem to have originated a distinctive style of their own, at least in the seventeenth century. Many of these Midland panellings evidently found their way to the south, as, for example, that in the Treaty House at Uxbridge, Fig. 342. This woodwork is, unquestionably either of Midland or Welsh bordering-county origin. It is interesting as showing the error of attributing panellings of the early seventeenth century to the localities in which they are found, at the present day. The chief characteristic of the Midland and Western-Midland panel is its heavy mouldings of the bolection type. The inner framed panel, as in the upper part of this Uxbridge panelling, also appears at an earlier date in these districts than in the East Anglian counties, where its presence is almost a certain indication of the later seventeenth century.

This Uxbridge wainscotting is neither choice in design nor high in quality, and it has suffered in alterations and adaptations, but it is instructive in showing that fixed panellings are not always original to the house they are in, even when they have been there for a century or two.

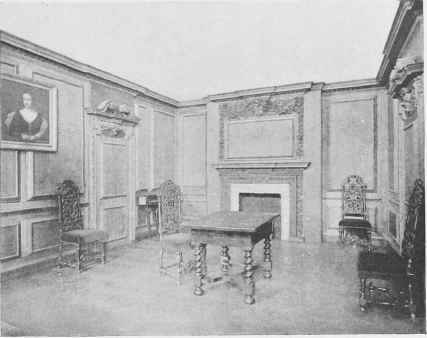

Fig. 371. The Oak-Panelled Room From Clifford's Inn. - General view. Date 1686-8. - Victoria~and Albert Museum.

The Western character of this Treaty House panelling can be better estimated by a comparison with an oak-panelled bedroom from Rotherwas, in County Hereford, illustrated here in Fig. 343. This is woodwork original both to the house it was in, - until its removal and sale a few years ago, - and to its locality. Here is the same heaviness of moulding and depth of panel-recessing as in the Uxbridge woodwork. When we place the Bromley-by-Bow room on the one side, - which is of Home County make, - and this bedroom from Rotherwas on the other, with the Uxbridge panelling between, the Western-Midland origin of the Treaty House woodwork will be appreciated.

Rotherwas, the home of the Bodenhams, whose shield of twenty-five quarterings can be seen on the fine mantel, Fig. 344, and the key to which is given in Fig. 346, is an estate which figures in Domesday, situated near the River Wye and within two miles of Hereford. It was de la Barre property until the death of the last male of the line, Sir Charles, in 1483, when Rotherwas came into the hands of Roger Bodenham as next-of-kin. There are innumerable Rogers in the Bodenham family history, and this one was the son of another, whose father, John Bodenham of Dewchurch, had married Isabella, heiress of Walter de la Barre. Thus the grandson inherited by reason of the alliance formed by his grandfather. The last direct descendant of the race who died in 1884, Charles de la Barre Bodenham, thus perpetuated, in his name, this last de la Barre of Rotherwas. Although not as lords of Rotherwas, the Bodenhams are of considerable antiquity in Herefordshire. In the reign of Edward I, William Bodenham is lord of Monington and many other parks and mansions in the valley of the Wye. Of the Rotherwas of the early sixteenth century, only a small part remains, converted into private chapels and adapted for the accommodation of the priests who had attached themselves to the Catholic Bodenhams.

Of the woodwork original to the early-sixteenth-century house, none appears to have survived. The great house of that period was neither panelled nor furnished in a day, and at Rotherwas there are signs that a century of possessors added to its woodwork. From the late period of Elizabeth dates the overdoor already illustrated in Fig. 307, but this appears to be the only remaining fragment of the sixteenth-century woodwork in the house.

Additions were built on by one of the many Roger Bodenhams in 1731, and to the new house many of the old panellings were removed. There are no records of work at Rotherwas in the early seventeenth century, yet at this period all the mantels and panellings shown in these pages must have been put in. Blount describes the house, in the seventeenth century, as "a delicious seat . . . abounding with a store of excellent fruit and fertyle arable land, having also a park within less than half a myle of the house. There is a fair parlour full of coats of arms according to the fashion of the age, and over that a whole Dyning Room wainscotted with walnut tree, and on the mantel of the Chimney twenty-five coats in one achievement."

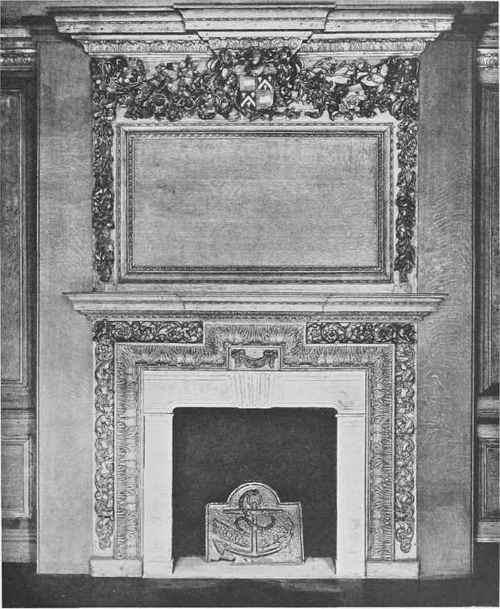

Fig. 372. Oak Chimney-Piece With Applied Carvings From Clifford's Inn. - Date 1686-8. - Victoria and Albert Museum.

Of the " fair parlour full of coats of arms," nothing remains, unless the overdoor, Fig. 307, was a part of the room. The description, however, reads more like a panelled room with painted armorial frieze-panels above, similar to the Abbot's parlour at Thame, and dating from the early years of the sixteenth century. The walnut panelling, with its oak chimney-piece and the " twenty-five coats in one achievement " are shown in Figs. 344 and 345. The use of walnut for this panelling is difficult to understand, as the tree is not a native of England, although some authorities assert that it was known here in the time of the Romans. There are records which state that the tree was imported from Persia and first planted at Wilton Park by the Earl of Pembroke and Montgomery about 1565. Apart from some liability to the attacks of the wood-worm (although the instance of the great roof of Westminster Hall shows the English oak is, by no means, immune from these ravages) it is a reliable wood for panellings, easy to work and carve, and obtainable in wide boards. Yet it does not appear to have been used for this purpose at any time, in England, even when it replaced oak as the popular wood for furniture. It is inferior to mahogany in durability, yet mahogany, also, is rarely, if ever used for panellings in the eighteenth century, when it was the exclusive furniture timber. The presence of walnut at Rotherwas is exceptional, but may have been imported. If the theory that the tree was first planted in England in 1565 be tenable, it could not have acquired a sufficient maturity to have been available for wide panels in the early years of the next century.

Continue to: