Chapter XII. Tables And Forms

Description

This section is from the book "Old Oak Furniture", by Fred Roe. Also available from Amazon: Old Oak Furniture.

Chapter XII. Tables And Forms

IN the history of tables we have not anything like such a retrospect as we have in that of other pieces of furniture. It is really astonishing how very few early examples can be referred to. Salisbury Cathedral, rich in other antiquities of a similar nature, possesses a genuine thirteenth-century example in its chapter-house, but this is almost a solitary instance of such a rarity. Like the remains of the famous Round Table at Winchester, it is quite unique and unapproachable, and altogether out of the sphere of the collector.

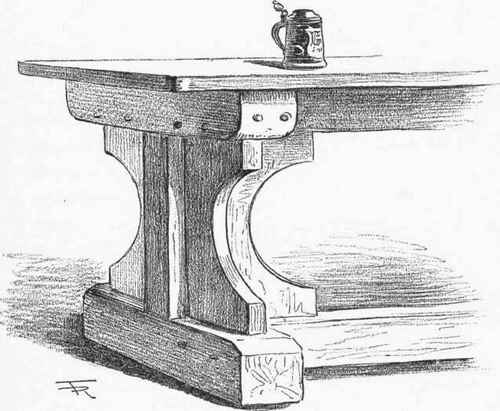

Mr. George C. Haite, R.I., of Bedford Park, Chis-wick, is the owner of a very remarkable early table, to which, for simplicity of design and construction, it would be hard to find a parallel. There is an entire absence of surface decoration from this piece, but its simplicity of form leads one to suppose that it belongs to Gothic times. Perhaps the most unusual feature about it is a sort of flying wing projecting on to the tread bar beneath the table, repeating in itself the lunette form of the ends. Though I have seen scores of tables of dates closely subsequent to the Reformation, both for high and humble use, I have never seen another to compare with this extraordinary piece. Its early history is difficult to trace with certainty, but there is good reason to believe that it was originally used in one of the foundation schools at Winchester.

EARLY OAK TABLE In the possession of George C. Haite, Esq., R.I.

Genuine tables of the Gothic period are exceptionally rare. The pseudo-Gothic productions made nowadays in France and Italy ought not to be regarded at all seriously; they are clever frauds with a too circumstantial history attached to each.

Of monkish tables there is an almost entire absence in England, for most of them were destroyed during the stormy times of the Reformation. A semicircular table exists in the abbey gate-house at St. Albans which came from the abbey church, and is traditionally said to be a monks' table. It is a rough, heavy-framed piece of work, entirely devoid of decoration, and with nothing about it to indicate that it belongs to pre-Reformation times; indeed, its shape and the character of the framing rather suggest that it is coeval with the gate-legged table of the seventeenth century. It is only fair to add, however, that the drawers with which it is fitted are later additions, and the probability is that the table was made for the use of Cromwell's troopers when they occupied the abbey.

That interesting historian, Agnes Strickland, describes an oaken table in the Tower of London which was said to be in existence during the reign of Edward V., and which actually received the murderous blow intended for the head of Lord Stanley when Lord Hastings was arrested in 1483. The story goes that Lord Stanley dodged the blow by getting beneath the table.*

The middle of the nineteenth century was not a period remarkable for the accuracy of such casual descriptions as this. Since Miss Strickland's day much has been done to the interior of the White Tower, where this episode took place, and whatever has happened to the aforementioned table, it is certainly now no longer there.

* 'Lives of the Bachelor Kings of England,' by Agnes Strickland. London: Simpkin, Marshall and Co., 1861.

An early table exhibiting roughly-carved pointed arches on its stretchers used formerly to stand in the Green Dragon Inn at Combe St. Nicholas, Somersetshire. The magnificent settle which remains at the same hostelry is described in another part of this work, but I am informed by a friend who has recently visited the place that the table is gone.

There is one very sufficient reason to account for the paucity of early tables remaining. During the feudal period and onwards to the change of habits of the new nobility, which took place during Tudor times, the great hall in the residences of the upper classes was used for a variety of purposes - such, for instance, as the representation of 'mysteries,' the entertainment of guests with dancing and minstrelsy, or such amusements as those provided by jongleurs and acrobats. The hall would necessarily have to be cleared for these diversions, a process which would be rendered more than difficult if the apartment contained cumbrous and From Tenier's picture ' The Card Players,' Ryks Museum, Amsterdam weighty pieces of furniture. 'Formes' we continually read about in manuscripts of the Gothic period, and the frequent occurrence of the term 'tressel-bordes' instead of tables clearly points to the use of articles which could be quickly and easily removed.

TABLE OF GOTHIC DESIGN.

This is not the only evidence we have. Painted illustrations in contemporary manuscripts of the fifteenth century frequently depict these light and portable pieces of furniture with remarkable accuracy, as well as the appearance of the hall when actually cleared of them for the purposes of after-dinner entertainment. To facilitate removal, tables were sometimes used with what is termed an independent top. In this variety, which is really a developed form of tressel, the legs, which were very massive, were not connected by framing, and were themselves unattached to the table proper, the mere weight of which gave the requisite steadiness to the whole structure. The legs were provided with spreading flanged feet splaying out from their base, and whatever the number of legs used, they were always placed under the centre of the table instead of at its corners. At Haddon a decaying table of this description remains in its original position on the dais of the Great Hall. In this instance the flanged feet project from the sides of the leg instead of being cruciform in plan. Some tables in the Great Hall at Penshurst, which are seven yards long, have the independent top, but they, together with their attendant 'formes' or benches, are placed at the sides of the hall, and not on the dais.

Continue to: