Bottle

Description

This section is from "The American Cyclopaedia", by George Ripley And Charles A. Dana. Also available from Amazon: The New American Cyclopędia. 16 volumes complete..

Bottle

Bottle, a hollow vessel, now generally made of glass or earthen ware, with a narrow neck. In ancient times, especially among the nomadic races, bottles were made of the skins of animals. Such are mentioned by Homer as being in use by the Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians. Herodotus describes the manner in which they were made by the Egyptians. The first distinct notice of them in the Bible is in the book of Joshua, where it is said the inhabitants of Gibeon "took old sacks upon their asses, and wine bottles, old and rent, and bound up." According to Chardin, the Persians preserve wine in skins prepared with pitch, which prevents the imparting of an unpleasant flavor to the wine. In Spain various skins-, and especially that of the goat, are still used for containing wine. The hide is stripped from the animal as entire as possible, and the various natural openings having been sewed up, with the exception of that of one of the legs, which is retained as a nozzle, the vessel is ready, after a certain preliminary curing of the skin, for the reception of the wine. The peculiar taste of Amontillado sherry is supposed to be due to its being kept in leather.

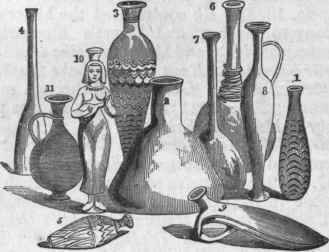

The only word rendered bottle in the New Testament is bonds, a skin or leathern bottle (Matt. ix. 17). In the Old Testament, however, earthen bottles are mentioned, as well as those made of skins. In the book of Jeremiah occurs the passage, "Thus saith the Lord, Go and get a potter's earthen bottle," etc. (xix. 1). Metal, earthen, and glass bottles were used in ancient times by the Egyptians, Assyrians, Greeks, and Etruscans. The Jews probably obtained their knowledge of them from the Egyptians. Kemains of Egyptian earthen and glass vessels, of various forms and sizes, have been found, and shown to have been made at a very early period. There is a collection of these articles in the British museum, and of elegant vases, which are assigned to a time as far back as that of Thothmes III., about 1450 B. 0. Glass bottles made several centuries B. 0. were found at Babylon by Mr. Layard. - The manufacture of glass bottles, on account of the nature of the material, is necessarily very simple, although for the production of fine work great skill is required. Glass while in a plastic state will not admit of much contact with machinery or tools without having its molecular constitution so affected as to increase its liability to fracture.

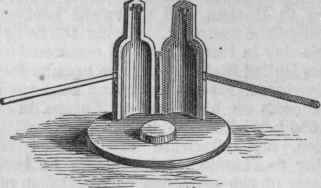

Therefore the finest bottles are blown, as they were in the earliest times, without the use of a mould, and with the aid of as few tools as possible; the operation being performed by simply gathering a proper quantity of molten glass upon the end of a metallic blowpipe, and forming it into shape by holding it in various positions while expanding it by blowing through the tube, and occasionally applying pressure with some tool of very simple form. Generally, however, bottles are made with the use of a mould in which the glass is blown, because in this way time and labor are saved. Fig. 3 shows the construction of a mould which is frequently used, especially in making small bottles and vials. It requires an extra hand, usually a boy, to open and shut it. For ordinary quart and pint bottles a mould is used with hinges at the bottom, and is closed by means of a lever which is moved by the foot of the operator. When this form of mould is used three hands are usually employed to make a bottle: one, a boy or apprentice, to gather the molten glass on the end of the blowpipe, one to blow the bottle and shape it in the mould, and a third to finish the neck and mouth and correct any defects in form. One person can perform the work, but not with equal economy of labor.

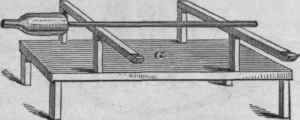

The operation may be briefly described as follows: Gathering the proper quantity of moltin glass upon the end of the blowpipe, which is a straight iron tube about five feet long, the gatherer hands it to the blower, who rolls it rapidly into a convenient form on the surface of a smooth iron or stone table, called a marver, at the same time expanding it slightly with the breath, then blows it to a suitable size for the mould, the axis of which is vertical. He then closes the mould, applies his mouth to the blowpipe, and blows with sufficient force to make the glass fit the cavity, and to take the impressions of whatever designs may have been engraved upon it. The mould is then opened and the bottle removed by means of the blowpipe, to which it still adheres. A punty, as it is called, is then attached to the bottom, to hold it during the finishing process. This punty is an iron rod, upon one end of which a small ball of red-hot glass has been gathered so that jt will adhere to the bottle, and it is applied as in fig. 5, the neck of the bottle being cut off by the application of a cold iron or a wet stick, accompanied by slight traction.

The finisher takes it, and, seating himself on a bench, a, fig. 6, which has some resemblance to an arm chair without a back, finishes the neck and mouth.

Fig. 1. - Skin Bottles.

Fig. 2. - Egyptian Bottles. 1 to 7, glass; 8 to 11, earthenware.

Fig. 3. - Mould.

Fig. 4. - Marver.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 6. - Finishing Bench.

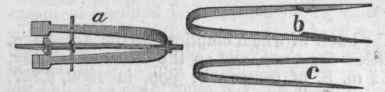

Generally a band of molten glass is wound around the neck, at the mouth, which is then held in a flame till it attains the proper degree of pliability, and the shaping is done with one or more of the tools a, b, c, fig. 7. The chief use of the arms to the bench is to allow a rotary motion to be given to the bottle, by which it is held in position and its form retained. After the mouth is finished the punty is removed, and the bottle is received on a wooden rod or in a holder and taken to the annealing furnace, where it is placed upon a pan, which, with several others attached together in the form of a chain, is drawn slowly through a long, horizontal oven. When the pan arrives at the opposite end of the oven, its load of bottles is removed and it is returned to the mouth of the oven to receive a new load. - A patent was obtained by Henry Rickets of Bristol, England, in 1822, for a machine for making bottles which was not unlike the moulds now in use, although more complex. It had a contrivance for forming the bottom by pressure from without, which is of no mechanical advantage, and only injures the texture of the glass.

Other patents for slight alterations in moulds have been obtained,. but their adoption causes but little change in the process of blowing, which, for reasons above stated, cannot receive much modification as long as glass is the material from which the bottle is made. - The various bottles used for different well known purposes are generally distinguished by peculiar shapes and sizes, as, for example, the English wine, beer, ale, and soda bottles, the French champagne, burgundy, and claret, and the Rhenish wine bottles. Port wine is occasionally put into very large bottles, called magnums, and acids in still larger, termed carboys. Demijohns are large bottles covered with wicker-work. The largest glass bottle perhaps ever manufactured was one blown at Leith, Scotland; its dimensions were 40 by 42 inches.

Fig. 7. - Finishing Tools.

Continue to: