Pitcher Plants

Description

This section is from "The American Cyclopaedia", by George Ripley And Charles A. Dana. Also available from Amazon: The New American Cyclopędia. 16 volumes complete..

Pitcher Plants

Pitcher Plants, a general name for plants with leaves wholly or partially transformed into receptacles for water. This occurs in plants widely separated botanically, and though the grouping of them together is not a scientific classification, it serves to present at one view several which have no other value than the interest which is attached to this peculiarity of structure. (See Leaf.) The water found in some of the ascidia, as the pitchers are botanically termed, may have been collected from rains, but in others the mouth of the pitcher is so protected that it is impossible for it to have been derived from this source, and it must be secreted by the leaf itself. Several plants collect rain water without having proper pitchers to receive it; a notable instance of this is the traveller's tree of Madagascar (Eavenala Madagascar ensis), the finest of the banana family; this has very large oval leaves, the sheathing petioles of which are distended at the base, forming a capacious cup into which the water that falls upon the blade of the leaf is conveyed by the channelled midrib and petiole; the thirsty traveller has only to pierce the base of the petiole to obtain a supply of fresh and limpid water.

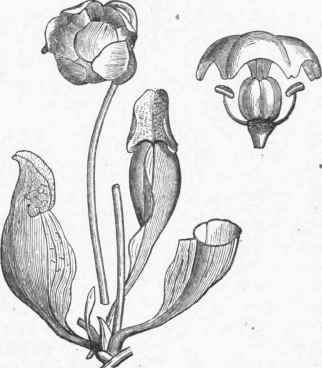

A similar collection of water takes place, though on a much smaller scale, at the base of the leaves of Tillandsia utriculata, a Florida plant of the related pineapple family, in which the base of the leaf is sufficiently dilated to hold several ounces of water; this plant being an epiphyte and found only growing on the trunks of trees, this may be regarded as a provision against drought. - Among the pitcher plants proper, our peculiarly North American genus Sarracenia presents in its six species several interesting forms; all these except one are restricted to the Atlantic states near the coast, from Virginia southward. The exceptional species is 8. purpurea, which grows from Florida to Newfoundland and extends westward as far as Minnesota, but west of the Allegha-nies is not found south of Ohio and Illinois; this was the first species made known, and upon it Tournefort founded the genus, which he dedicated to Dr. Sarrazin of Quebec, who forwarded the plant with a botanical account of it to Europe. The sarracenias are bog-loving perennials, and have tubular leaves in a radical cluster; the leaves vary much in size as well as in form and color in the different species, and in all are marked by a network of veins; structurally these pitchers, or trumpets, as they are often called, are regarded as leaves with a very broad petiole, which is joined at the edges to form a trumpet-like tube, the suture where the edges unite being marked by a wing running the whole length; the proper blade, very small in proportion to the petiole, appears as an appendage at the end of the tube, called the hood or lamina, and is regarded as the lid of the pitcher, though it never closes it, but in some species bends over the opening and more or less covers it.

The pitchers have their inner surface clothed with stiff hairs pointing downward, and in one species at least there is near the orifice of the tube a sweetish exudation. The tubular leaves or pitchers are found partially filled with water containing numerous dead and more or less decomposed insects. From the centre of the cluster of leaves the naked flower stalks are produced, each of which bears a large, solitary, nodding flower; the calyx, with three bractlets at its base, has five persistent, thick, colored sepals; the five oblong petals are incurved over the pistil and deciduous; the globose five-celled ovary has a short style surmounted by a broad umbrella-shaped expansion, which is petal-like and five-angled, and has five delicate rays starting from the centre, and terminating under the angles on the margins in as many minute hooked stigmas; the numerous stamens are inserted below the ovary and covered by the umbrellalike expansion of the pistil. The northern species, S. purpurea, is quite common in peat bogs within its limits, and is popularly known as pitcher plant, huntsman's cup, and sidesaddle flower, the last name being of obscure application, though the flower is shaped somewhat like a pillion, the leaves, 4 to 6 in. long are curved upward, have a broad wing and a short, erect, open hood; they are often veined with purple and tinged with that color; the flower, 'on a stalk a foot high, is deep purple: a rare variety has yellowish green flowers and leaves without purple veins.

A few years ago the root of this was much lauded as a remedy for smallpox, and wonderful cures by it were reported in England; careful trials in this country have shown it to be quite valueless. The parrot-beaked pitcher plant (S. psittaci-na) is the smallest species; its leaves, only 2 to 4 in. long, marked with white spots and purple veins, are spreading, with the hood inflated, beaked, and so bent over as to cover and protect the orifice of the tube; the flower stalk is a foot high, the flower purple; this is confined to the pine-barren swamps of Georgia and Florida. The red-flowered trumpet-leaf (JS. rubra) is found in the sandy swamps of North Carolina and Georgia; its trumpet-shaped leaves, 10 to 18 in. long, are erect, paler above and marked with purple veins; the hood is erect, ovate, with a point or beak at the top and hairy on the inside; the flower stalks, taller than the leaves, have reddish purple flowers. Drummond's pitcher plant (S. Drummondii) occurs in the swamps of Florida and middle Georgia; its erect trumpet-shaped leaves are 2 ft. long, and are the showiest of all, as the upper part of the tube and the erect hood are white, handsomely marked and netted with purple veins; the flowers, 3 in. across, are purple.

The spotted pitcher plant (S. va-riolaris), found from North Carolina to Florida, has its erect leaves 6 to 12 in. long, the ovate hood concave and arching over the opening in the tube, which is yellowish near the top and spotted with white; the flowers, about 2 in. broad, are yellow and on stems shorter than the leaves. The largest species is the yellow pitcher plant (S. flava), called trumpet-leaf, trumpets, and watches; the erect leaves have a wide mouth, and an erect rounded hood, which is narrowed at the base and yellow; they are 2 to 3 ft. long and of a light yellowish green color; the flower stalks, about as long as the leaves, have yellow unpleasantly scented flowers 4 or 5 in. across, the petals becoming long and drooping; this species is found from Virginia to Florida, often occurring in large tracts. Sarracenias are much cultivated by collectors of interesting plants; the common species (8. purpurea), set in a vase or bowl of peat moss and properly supplied With water, makes a pleasing window plant, but the others require greenhouse treatment; they grow best in a mixture of sphagnum moss and peat, and require an abundance of water while growing, and but little while at rest. - On the Pacific coast the Sarraceniaceae are represented by a most interesting genus,' Darlingtonia, of which but one species, D. Californica, is known.

Its chief botanical difference from Sarracenia is in its five-lobed style; the shape of the leaves is very unlike any in that genus; when full grown, they are from 12 to 18 in. long, tubular and dilated upward, with a broad wing, and singularly twisted about half a turn; the summit of the tube is vaulted and curved over like a hood, beneath which is a small orifice; the blade of the leaf is represented by an appendage at the end of the tube, of two diverging lanceolate lobes and shaped somewhat like a fish's tail; the upper portion of the tube is beautifully mottled with white and netted with pinkish veins; the flower stalk, from 1 to 4 ft. long, is furnished with straw-colored scales, and bears a single nodding flower about 2 in. in diameter, with five straw-colored sepals and as many purple petals. The leaves contain water in which large numbers of insects are drowned; the orifice of the tube is so completely protected that it is well nigh impossible that the liquid should be other than a secretion of the plant.

This was first found by the botanist of the "Wilkes exploring expedition in 1842 on the upper Sacramento, and has since been found in other localities; it was described by Torrey, who dedicated it to the late Dr. William Darlington of West Chester, Pa. The Darling-tonia, succeeds admirably in cultivation with the same treatment required by sarracenias. Another genus of the same family is Tieliam-phora, also American, but found only in the mountains of Venezuela; its leaves are open pitchers with an oblique mouth, as if the pitcher were not quite completed, and the blade, so strongly developed in Darlingtonia, is reduced to a minute concave appendage at the apex; this differs from the other genera in having several flowers upon the stem, which are small, nodding, white, or pale rose-colored. There is but one species, H. nutans, which does not appear to have been brought into cultivation. - The Australian pitches plant, the smallest of all, is cephalotus follicularis (Gr. ![]() , headed, in reference to the form of the stamens). There is but one species, which inhabits the swamps in King George's sound. It has a very short stem, bearing ordinary leaves of an oblong or elliptical form, and also others which are dilated to form neat little pitchers; intermediate stages between the pitchers and the ordinary leaves have been observed, showing them to be leaves peculiarly modified.

, headed, in reference to the form of the stamens). There is but one species, which inhabits the swamps in King George's sound. It has a very short stem, bearing ordinary leaves of an oblong or elliptical form, and also others which are dilated to form neat little pitchers; intermediate stages between the pitchers and the ordinary leaves have been observed, showing them to be leaves peculiarly modified.

Northern Pitcher Plant (Sarracenia purpurea).

California Pitcher Plant (Darlingtonia).

Venezuela Pitcher Plant (Heliamphora).

The pitchers are from 1 to 3 in long, and in a well grown plant are arranged in a close circular tuft; each has two strong hairy ribs in front and one on each side; they are green, spotted and shaded with purple or brown. At the top of the pitcher is a much thickened rim, which- is handsomely and regularly grooved, and against it the concave, hairy, pink-veined lid neatly fits. The flowers, which are not showy, are borne in a long spike; each has six pistils, which ripen a single seed each. This genus has been a troublesome one to botanists, who have placed it in several different families, including one proposed especially for it; Bentham and Hooker, in Genera Plantarum, admit it as an anomalous genus of the saxifrage family. - Some species of dischidia, a tropical genus of milkweeds (asclepiadacea), are to be enumerated among pitcher plants; these climb to the tops of the tallest trees, and among their upper leaves are some which are developed as pitchers, while others retain their normal form. - The most striking of all the pitcher plants are furnished by the genus nepenthes.

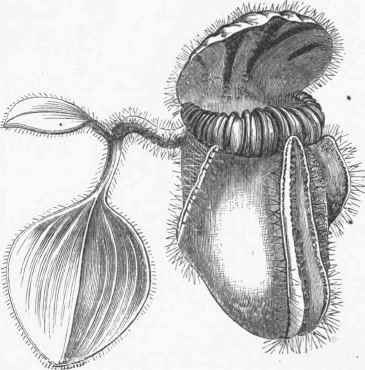

They are inhabitants of tropical swamps in the East Indies, Madagascar^ Australia, and New Caledonia, and now number over 30. The genus, while it presents affinities with several families, is too unlike all others to be united with them, and stands in a family by itself, nepenthew, near the birth-worts (aristolocMacece). The plants are half shrubby with prostrate or trailing stems; the apetalous flowers are dioecious, in a slender raceme; the male flowers have a four-parted calyx, with about 16 stamens united into a column to which the united anthers form a spherical head; the female flowers have a three- or four-cornered ovary, with as many cells, the numerous ovules in which ripen into elongated seeds with a very long, loose, membranous coat. The alternate leaves have the petiole winged at the base; above this wing the midrib is greatly prolonged, curved or spirally twisted, and at the end expanded into an urn or pitcher, the mouth of which is furnished with a lid attached by a sort of hinge, and is sometimes open and sometimes closed; the lid does not open until the leaf is completely developed, and before this takes place the watery liquid is secreted and partly fills the pitcher.

These wonderful leaves have been erroneously said to secrete water for the use of travellers in arid regions where no other supply exists; the fact is that the plants are only found in swamps, and cannot endure a dry atmosphere. The pitchers vary greatly in size and form, and also in color and markings. The species first introduced, and for a long time the only one in cultivation, N. distillatoria, has narrow cylindrical pitchers, 6 or 8 in. long, which are of the same light green color as the leaves; this is the easiest of cultivation, enduring a lower temperature than the others; its variety rubra, a chance seedling, has the pitchers of a deep blood-red color, and is ornamental and rare. The species is so abundant in Ceylon that the natives use the strong midribs for cords and withes. N. phyllamphora and N. gracilis are other species having green pitchers. Some have the pitchers handsomely variegated; of these N. Raffiesiana may be taken as an example; it is a very robust plant, with pitchers 6 to 12 in. long; the mouth of the pitcher has a handsomely annulated border and a large lid; each side of the front is a broad wing, fringed with long hairs upon the edge; the leaves are dark green, and the pitchers are of the same color beautifully spotted and blotched with red.

As the plants of this and some allied species become old their pitchers assume a very different shape; in the young leaves they are largest at the base, have two wings in front where the midrib is attached, and the oblique mouth of the pitcher looks toward the midrib; in the old plant the base is much narrowed, the wings are wanting, and the mouth of the pitcher looks from the midrib; were it not that every intermediate state occurs on the same plant, the two extremes would be taken as belonging to different species. The nepenthes are increased by cuttings and sometimes by seed; for their cultivation they require a moist atmosphere and a temperature not less than 70°; they are usually grown in baskets of peat and sphagnum and abundantly supplied with water. - The various pitcher plants have of late been regarded with new interest; always noticeable for their unusual structure, and. long cultivated as objects of curiosity, the investigations of Darwin and others upon the relations of plants and insect3 have led to new observations upon the various pitcher plants.

To what is said in the article Insectivorous Plants in regard to Sarracenia it may be added that Dr. Mellichamp of South Carolina has observed that in S. variolaris, " not only is honey secreted in numerous drops around the inside of the mouth, but that there is actually a trail of it, when the leaf is in its fullest vigor, running down the margin of the wing to the ground, the whole forming a most effectual lure to honey-loving insects." Recent observations have shown that Darling-tonia is also provided with a bait to entice insects to the hidden orifice of its tube; the fishtail-shaped appendage at the top has been found to be " smeared with honey on the inner surface." While botanists have been busy with the plants, the entomologists have studied the insects found in the pitchers of Sarracenia. Prof. C. V. Riley of St. Louis finds that while the dead insects found in the pitchers are numerous species of all orders, there are two which "brave the dangers of S. variolaris" and make their home in its leaves; one of these is a small moth, xanthoptera semicrocea, the larva of which makes a web just within the mouth of the tube and feeds upon its substance; the other is a flesh fly not before described, sarcophaga sarracenia^; the female drops her living larvre into the tube to the number of a dozen or more; these feed upon the soft parts of the dead insects accumulated in the tube and upon one another, so that only one of the larvse usually matures, the rest having fallen victims; the maggot finally makes its way through the base of the tube, burrows in the ground, and there is transformed.

Australian Pitcher Plant (Cephalotus follicularis).

Nepenthes distillatoria.

Continue to: