Yam

Description

This section is from "The American Cyclopaedia", by George Ripley And Charles A. Dana. Also available from Amazon: The New American Cyclopędia. 16 volumes complete..

Yam

Yam, the popular name for plants of the genus Dioscoroea (named in honor of the Greek naturalist Dioscorides), and in the southern states applied very generally to light-colored varieties of the sweet potato. (See Potato, Sweet.) It is the type and most important genus of a small order of endogenous plants, the Dioscoroeaceoe, or yam family, mostly tropical, with large tuberous or knotted roots, twining stems, and small dioecious flowers; another genus is described under Tortoise Plant, and the engraving there given illustrates the general appearance of the yams as to vine and foliage. The leaves in Dioscoroea are petioled, alternate, but sometimes opposite, and nettedveined; the flowers are in small axillary racemes or panicles, the sterile consisting of a six-parted perianth with as many stamens; the fertile of a three-celled ovary surmounted by a perianth, and three styles, and ripening into a three-winged, three-celled pod, which when ripe splits through the wings to liberate the one or few seeds contained in each cell.

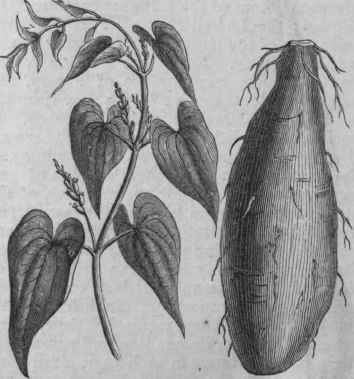

Though generally tropical, one species, D. villosa, the wild yam, is found as far north as New England, and is very common southward; it grows in thickets, running over bushes, and is conspicuous in the autumn by its large clusters of pods, which are much in request for skeletonizing and for winter bouquets; though called D. mllosa, the plant is usually nearly smooth, or at most the leaves are slightly downy below. The leaves, commonly alternate, are sometimes opposite, and even in fours, heart-shaped at base, conspicuously pointed at the apex, and with 9 to 11 strong ribs; flowers greenish yellow. On account of its pleasing, dense foliage, this is sometimes cultivated to cover low screens and arbors. The yams cultivated in tropical countries, and occasionally as a curiosity in the southern states, all form very large, thick, tuberous roots, differing in size, shape, and color; they sometimes weigh 30 or 40 lbs., and are irregular shapeless masses, or turnipshaped and 3 ft. or more long; some are white and others purplish throughout, and the skin is of various shades from whitish to nearly black.

There are many varieties, derived from D. sativa, D. alata, D. aculeata, and several others, all natives of the East Indies; having been long cultivated in the "West Indies and South America, some have become naturalized in those countries, in which there are also several native species. The roots contain a large amount of starch, about 25 per cent, in some, but they are rather coarse, and are not generally esteemed by Europeans; they are eaten either roasted or boiled, and a meal is prepared from them for use in puddings and cakes. Occasionally the roots are imported, chiefly as an attractive curiosity at the West India fruit stores. When the rot, about 1845, threatened the extermination of the potato, a general search was made for some edible tuber or root that would serve as a substitute; among those proposed, none were more prominent than the Chinese yam (D. batatas, or D. Japonica of some), which had been long in cultivation in China and Japan, and which was introduced into Europe by the French consul at Shanghai, and soon after was brought to this country, where for a while it created much interest.

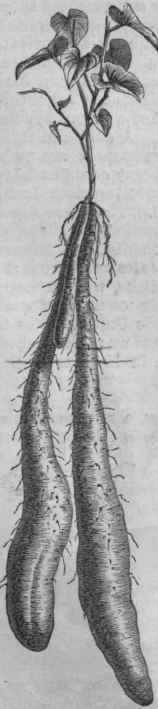

It forms a long club-shaped root, 2 ft. or more long, and largest at the lower end; the vines run from 10 to 20 ft. in length, and have rich, dark green, heartshaped leaves, in the axils of which are produced bulblets smaller than an ordinary pea, from which, or from cuttings of the upper portion of the root, the plant is propagated. The root is remarkably white within, rather mucilaginous, and when cooked is much esteemed by many, but, lacking the dry starchy character of the potato, not likely to be generally popular; it is boiled, roasted, or fried. The great obstacle to its general cultivation is the difficulty of taking the crop; the depth to which the roots go perpendicularly downward makes the digging of them very expensive; their shape, being largest below, renders it impossible to pull them, and their extreme brittleness makes it exceedingly difficult to extract them without breaking. The plant is perfectly hardy, and the roots remain in the ground during the severest winters without injury. Its cultivation is now confined to amateurs who are willing to be at the trouble of digging the roots, and it is sometimes 6een growing as an ornamental vine; animals are fond of the herbage, and it has been proposed in France to grow it as a forage plant, sowing the bulblets broadcast.

A variety or species, Decaisne's yam (D. Decaisneana), has been recently introduced into France; its roots are inferior in quality to the preceding, and not so large as an ordinary potato.

Yam (Dioscoraea alata).

Chinese Yam (Dioscorsea batatas;.

Continue to: