Permian Life

Description

This section is from the book "An Introduction To Geology", by William B. Scott. Also available from Amazon: An Introduction to Geology.

Permian Life

We have to note, in the first place, that the animals and plants of the Permian are transitional between those of the Palaeozoic and those of the Mesozoic eras. Here we find the last of many types which had persisted ever since Cambrian times, associated with forms which represent the incipient stages of characteristic Mesozoic types, together with others peculiar to the Permian.

Plants

The flora of the Lower Permian is decidedly Palaeozoic in character, and that of the Upper Permian as decidedly Mesozoic, so that if the line dividing these two great eras were drawn in accordance with the vegetation, it would pass through the Permian. Even in the Lower Permian, however, the change from the Carboniferous flora is a marked one, a change which may be largely explained by the increasing aridity of the climate. The great tree-like Lycopods, Lepidodendron and Sigillaria, which were so abundant in the Carboniferous forests, have become very rare; none of the former genus and only two of the latter have been found in the Upper Barren Measures of Pennsylvania and West Virginia. The Catamites continue in hardly diminished numbers and importance. The Ferns are exceedingly abundant and varied, and tree-ferns seem to be more common than they had been before. Especially characteristic genera of these plants are Pecopteris, Callipteris (Fig. 276), Cynoglossa, Neuropteris, Sphenopteris (Fig. 277), etc.

The Gymnosperms mark a notable advance; in addition to the ancient Cordaites, are true Cycads and Conifers; of the latter are found yew-like forms, Walchia, Saportcea with leaves nearly four inches wide, and the Gingkoacece are probably represented by Baiera.

In the Upper Permian, Lepidodendron, Sigillaria, and Calamites are quite unknown, though probably a few stragglers still existed, and the flora is made up of Ferns, Cycads, Gingkos, and Conifers, the Angiosperms still being entirely absent.

The Permian flora of the southern land mass differs notably from that of the northern continents and is characterized especially by the broad-leaved ferns, Glossopteris (Fig. 278) and Gangamopteris, whence this is often called the "Glossopteris Flora," together with the cosmopolitan Callipteris, the Conifer Voltzia and the Calamite Schizoneura. In South America and South Africa, but not in India or Australia, these plants are accompanied by some survivors from the Carboniferous, such as Lepidodendron. In the latter part of the Permian, or possibly not till the earliest Triassic, the Glossopteris Flora invaded the northern continents and extended its range to northern Russia {Tataric stage).

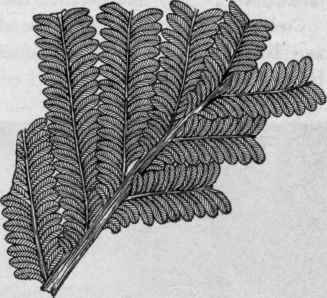

Fig. 277. - Sphenopteris coriacea F. and W. (Fontaine and White).

Fig. 276. - Callipteris conferta Brngn. (Fontaine and White).

Foraminifera are almost as important in the purely marine limestones as they had been in the Upper Carboniferous.

Coelenterata

The Corals are still mostly of Palaeozoic type and belong to Carboniferous genera, but some of the modern Hexacoralla have appeared.

Fig. 278. - Glossopteris browniana Brngn. Newcastle, Australia.

Echinodermata

This group has dwindled in the most remarkable way, and instead of the abundance of Crinoids which flourished in the Carboniferous seas, are found only occasional specimens.

Arthropoda

The last few stragglers of the genus Phillipsia indicate the extinction of the great Palaeozoic group of Crustacea, the Trilobites, which henceforth we shall meet with no more; the Eurypterids have their latest known representatives in the little coal basin of Bussaco, in Portugal, which is referred to the Permian, though with some doubt. In the Kansas Permian have been found numerous insects, which, though resembling those of the Carboniferous in a general way, all belong to species different from those of the latter. The giant insects of Commentry in France, which have been mentioned in the chapter on the Carboniferous, are now referred to the Permian by many authorities.

Bryozoa are prominent in all marine formations, sometimes forming reefs.

The Brachiopoda are still very abundant, especially in the Lower Permian; they are closely allied to those of the Upper Carboniferous, and, as in that period, the Productids play the most important role, though many of the species are peculiar to the Permian. The curious sessile, irregularly shaped Richtho-fenia, which began in the late Carboniferous, is especially characteristic of the Permian limestone accumulated in the Mediterranean Thetys, as in Asia, Sicily, and western Texas.

Mollusca

In this group very striking changes are to be noted. The Bivalves increase materially in variety, and in addition to ancient genera like Aviculopecten (XII, 13) and Myalina (XII, 12) the typically marine Permian has many new forms, such as Area, Lucina, Lima, Bakevellia (XII, 14), Pleurophorus (XII, 15), Pseudomonotis (XII, 16), etc. The Gastropods require no particular mention, except for the great abundance of the genus Bellerophon (XII, 17). It is among the Cephalopods that the great advance takes place. Orthoceras and Gyroceras continue from the older periods, and many species of the genus Nautilus are added, but the chief fact consists in the presence of Ammonoids with highly complex sutures, far exceeding, in this respect, the Goniatites of the Carboniferous, some of which continue to exist alongside of the more advanced forms. The more important new genera of Ammonoids are Medlicottia, Ptychites, Popano-ceras, Waagenoceras (XII, 20), which have been found in Texas, Sicily, Russia, and India. The presence of these remarkable shells gives a strong Mesozoic cast to the Permian fauna.

Vertebrata

The Fishes are still of Carboniferous types, and many of the same genera occur, while new ones are brought in. To the Sharks are added the curious Menaspis, which is armed with numerous long and curved spines. Among the Dipnoi the genus Ceratodus, very closely allied to the modern lung-fish of Australia, makes its first appearance.

The Amphibia are represented, as in the Carboniferous, by the Stego-cephalia, and several of the older genera persist, but many new forms appear for the first time, several of which much surpass the Carboniferous genera in size. (See Fig. 280).

The most important character that distinguishes the life of the Permian from that of all preceding periods is the appearance in large numbers of true Reptiles. There is no reason to suppose that such a variegated reptilian fauna can have come into existence suddenly, and their ancestors will doubtless be discovered in the Carboniferous ; but while no true reptiles are certainly known from the latter, in the Permian they are the most conspicuous elements of vertebrate life. These reptiles belong to several orders, one of which, the Proganosauria, is represented by Mesosaurus in South Africa and by Stereosternum in South America. The Proterosauria are a very central group, from which many other reptilian orders appear to have descended:

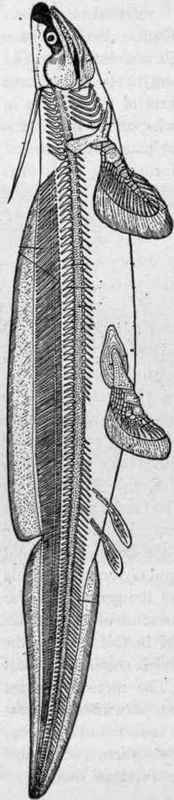

Fig. 279. - Pleuracanthus decheni, x 1/3. (Dean after Fritsch).

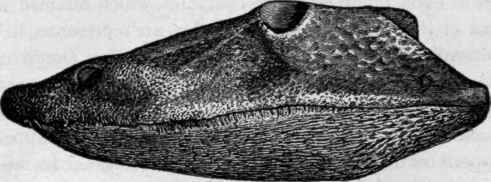

Fig. 280. - Permian Stegocephalian, Eryops megacephalus Cope, x 1/7. Skull seen from side. (Cope).

Proterosaurus and Palceohatteria are the most important Permian genera of this group.

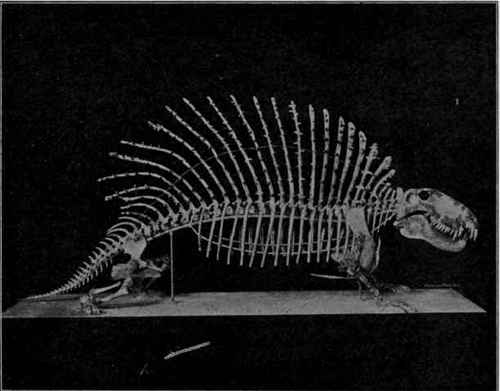

Fig. 281. - Permian Pelycosaurian, Naosaurus clavlger Cope. (Osborn).

The Pelycosauria are extremely curious animals found in Texas and Bohemia, These, were carnivorous land reptiles which had short tails and enormously elongated, sometimes branching, spines in the back (Fig. 281). The Cotylosauria, heavy massive reptiles of exceedingly primitive character, which retained several features of the stegocephalous Amphibia, are represented in Texas by two families, including several genera, of which Diadectes may be selected as typical. In South Africa is found the extraordinary Pareiasaurus, of the same order. Pareiasaurus followed the Glossopteris Flora in its northward migration and appears in the uppermost Permian of Russia (Tataric stage). In the same stage of the Russian Permian are found two other orders, which likewise seem to be migrants from South Africa, for they are abundantly represented there, the Anomodontia, with turtle-like beaks and either no teeth or a pair of large tusks, and the Therio-dontia, the latter also found in Bohemia.

Continue to: