Country Clubs And Hunt Clubs In America. Part 2

Description

This section is from the book "The Out Of Door Library: Athletic Sports", by D. A. Sargent. Also available from Amazon: The Out of Door Library, Athletic Sports.

Country Clubs And Hunt Clubs In America. Part 2

The Brook-line Country Club is about five miles from the busi-ness centre of Boston. Good roads lead to it from all directions, and make it accessible by driving from Boston and most of the suburban cities and villages that environ that fortunate town. The grounds of the club include acreage enough for a half-mile track, a course for steeplechasing, a polo-field, golf-links, and as many tennis-courts as are called for, besides woodland, shaded avenues, and long stretches of lawn. The club-house, facing the lawns and polo-field, stands back several hundred yards from the street, from which a shaded avenue leads to it. It is the house that was bought with the estate, and enlarged to meet the requirements of the club.

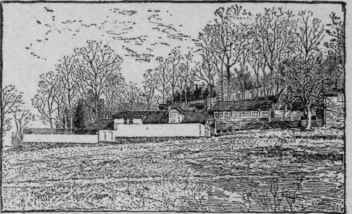

The Radnor Kennels.

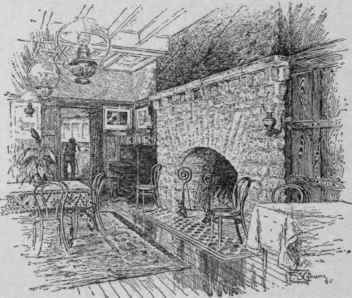

A Corner of the Dining-Hall.

Without any violent pretensions to architectural beauty, it is handsome enough, and has reception-rooms, ball-rooms, dining-rooms, billiard-rooms, bath-rooms, bedrooms, and piazza-room enough for the club's necessities. Its stables are proportionately ample and convenient. Its activities continue all the year round; but as a large proportion of its members get them to the seashore or elsewhere in summer, its liveliest times are in the spring and fall. Steeplechasing, flat-racing, pony-racing, coursing, and gym-kana games are its habitual exercises; and occasionally it holds a sort of blizzard of sport, when a horse-show, a dog-show, or some other sporting spectacle, is provided every day for a week. The activity of its polo-players is continuous all through the season; and golf, which is a godsend to country clubs, has already taken an important place in its activities. It will be seen that this club abounds in what the theatrical managers call "attractions." When anything of special moment offers, its grounds are gay with fair women, brave horses, bicycles, grooms, carriages, and gentlemen; and when nothing in particular is going on, it is still a pleasant place to drive to and get dinner.

The Radnor Hunt Club of Philadelphia, quartered near Bryn Mawr.

What the Brookline Country Club is, most of the other country clubs are, or hope to be, always with such differences as environment contributes. Such clubs as the Essex County, the Catonville, or the Westchester, placed in a centre of summer homes, are liveliest in summer; while the hunt clubs which have country-club features are most active in the fall.

Most of the hunt clubs are the outcome of the same development of wealth, leisure, and sporting proclivities to which the rise of the country clubs is due.

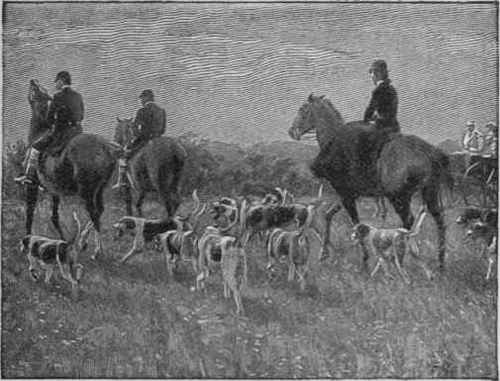

Hunting in England seems to have grown originally out of the necessities of country life. For centuries the most important form of British wealth was land. All important Englishmen had landed estates; most of them got their chief revenues from them, and most of them lived a good part of the year in one or another of their country places. They had to amuse themselves as they could. The habit of the chase came down to them from remote times; and when they had no wild creature left that was chasable but the fox, they cherished the fox, and duly and diligently pursued him. In some parts of the United States it has happened that, ever since the country was first settled, foxes have been chased by country gentlemen, who needed some active sport to beguile their seasons of leisure. Thus it was in Virginia, so long before the Revolution that, when Lord Fairfax and George Washington kept hounds and hunted them, fox-chasing was an old story to the horsemen of those parts. But our modern American revival of fox-hunting and crosscountry riding springs not so much from the need of beguiling the monotony of the lives of landed proprietors and country gentlemen, as from the necessities and aspirations of city men. Fox-hunting, or even drag-hunting, is an expensive amusement; and though in country districts where it has been started the farmers oftentimes share its excitements and help it on, the revenues of agriculture do not often suffice for its support. In some few exceptional cases the sport has been a true local development of the country hunted; but much more often is it a suburban enterprise, originated and supported by city men who want to hunt, and whose business, if not their homes, is in town. Out of twenty-five American and Canadian hunt clubs, at least twenty have this suburban characteristic. It is partly due to local conditions, and especially to the fact that this is a country of small farmers, who own their farms, instead of landed proprietors and tenant farmers. But it is also a result of that world-wide, contemporaneous tendency which is making all the great cities bigger, and many of the lesser towns great; so that even in Great Britain the two hundred, more or less, hunts which flourish in spite of hard times, doubtless draw a very much more important proportion of their support from city men than they did twenty-five or even ten years ago.

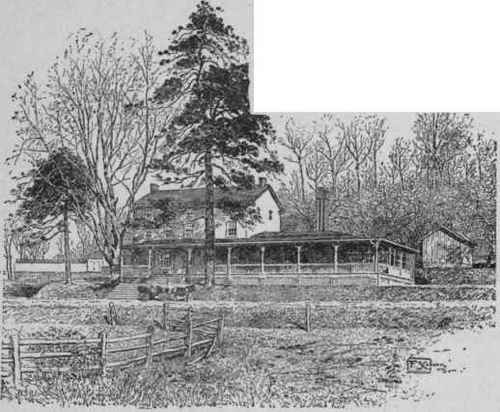

Start of the Meadowbrook Club at Southampton.

The city man's desire to hunt is based neither on affectation nor on mimicry. Americans do not hunt foxes or ride across country because it is done in England. The strain of English blood may show itself, perhaps, in American horsemanship; but Americans ride across country because that is a far livelier and more interesting form of riding than riding on the road, even when it is a country road, - much more so when it is a park road or a paved street. And when Americans hunt foxes, they do it for the same reason that the English do, because following the trail of a fleet and wily animal is better sport than following a cross-country trail artificially laid, and because the fox is the only wild creature fit for the chase that will live and flourish in proximity to man. That the city man, be he Briton or American, should wish to hunt is a reasonable desire. The circumstances of his daily life are such as draw on his vitality and abate his vigor. When once he has put himself in the way of making an adequate living, his physical life is apt to be easy. He gets no taste of cold or hunger and hard physical labor. He is too apt to be overfed and overheated, to drink more than is good for him, to work too hard with his head and too little with his body, to be luxuriously lodged, and generally to be made too insidiously comfortable. He has to fear the debilitating influences of such a life, both on his physique and on his character. His simplest remedy is some sort of out-of-door exercise which involves some self-denial, some exertion, and a reasonable amount of grit. Partly for his liver's sake, partly for his amusement, he gets astride the horse. Then, if he has in him the quality known as sporting-blood, mere horseback exercise presently palls on him. It is too monotonous.

Continue to: