St. Petersburg. Part 12

Description

This section is from the book "St. Petersburg and Moscow - John L. Stoddard's Lectures", by John L. Stoddard. Also available from Amazon: John L. Stoddard's Lectures 13 Volume Set.

St. Petersburg. Part 12

The River.

In striking contrast, however, to this splendor, the private apartments of the Russian sovereigns are extremely plain. I was especially impressed with the austerity of the bedroom of the Emperor Nicholas, where he died of a broken heart, because of the disastrous results of the Crimean War. The room remains as when he occupied it. Probably no reader of these pages has one so plain; for the floor is carpetless, and the bed is a narrow frame of iron. On the walls are a few simple pictures of Sevastopol, and on the floor is a pair of slippers that he wore for years, and which, it is plain to see, were often mended.

What was true of Nicholas, was true also of his son. The study of the Emperor Alexander II. is very simply decorated. The furniture is upholstered in leather, and only a few portraits of his children, relatives, and soldiers adorn the walls. Whether the old domestic, who showed us through the palace, suspected that we had dynamite about our persons, I know not; but he seemed quite reluctant to admit us to these private rooms. Accordingly, our guide informed him in a whisper that we were really Russians of high rank, who, since we were traveling incognito, chose to speak a foreign language.

The Chinese Room.

I was not responsible for this lie; but either that, or a rouble slipped into his hand, produced the desired effect, and we were admitted.

In our subsequent tour of the palace, I was in constant dread lest that servant should ask us for our Russian titles. In that event we should have had to resort to the device of three Americans who, on their travels here, had taken Russian names. These proved so difficult to remember and pronounce, that finally they invented some far easier to recall, since they were based on their respective looks or occupations. Thus, one who practiced dentistry, called himself " Count Pull-a-Tusky"; the second, who was a distiller, took the title of " Prince Cask-O'-Whisky" ; while the third, who had the misfortune to be bald, was styled by his companions, "General Hair-all-off."

The Bedroom Of Nicholas.

The Study Of Alexander II.

A good story is told of the Tsar Alexander I. One morning, entering with his wife the elegantly furnished boudoir of the Empress, they found, on the table, a small package awaiting them. That was before the days of Nihilism and of dynamite - hence the Emperor opened it without hesitation. It proved to be a volume of poems written by a man who, although talented and witty, was poverty-stricken, as indeed most poets have always been. The Emperor read the book, and was so well pleased with its contents, that he caused a hundred bank-notes, of one hundred roubles each, to be bound in a book, and wrote on its title-page the words, " Poems of the Emperor Alexander."

The Reception Hall Of The Empress.

Group At Railroad Station.

/

This he sent to the needy poet. Soon after this act of imperial generosity, a ball was given here. Among the guests was the delighted poet, who hastened to the Tsar to express his thanks. "Well," said Alexander, "how do you like my poems?" "Very much, indeed, Sire," was the reply, " as far as I have read them; but I have as yet seen only the first volume." The Tsar smiled, and the next day ordered another similar book of bank-notes to be made, entitled, " Poems of the Emperor Alexander : Volume Second." This time, however, on the last page the Emperor had written with his own hand, " The End."

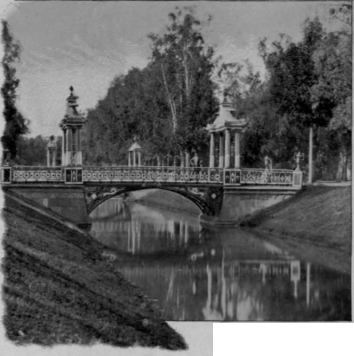

Rivaling Tsars-Koe-Selo in interest, is Peterhof, - another summer residence of the imperial family, also in the vicinity of St. Petersburg. No sooner had we entered its extensive park than we found ourselves in the midst of a multitude of fountains, which in number, design, and beauty are unsurpassed, even by those of Versailles. Peterhof is another result of the indomitable energy of Peter the Great. If Louis XIV., he said, had created fountains on a sandy plain near Paris, why should not he do as much along the marshes of the Neva? With Peter no delay was possible. Within two months after the autocrat's order had been given, the thousands of workmen, whom he had summoned to the prodigious task, announced that the canals and aqueducts were ready. Another army of laborers was equally expeditious in the construction of the palace, avenues, and villas. Statues and ornaments, also, sprang up as if by magic; and since trees were already abundant, the entire park and buildings of Peterhof were constructed within a year. In his impatience, Peter is said to have felled many trees himself, swinging the ax with a force that none of his workmen could equal.

Continue to: