Spain. Part 20

Description

This section is from the book "Spain - John L. Stoddard's Lectures", by John L. Stoddard. Also available from Amazon: John L. Stoddard's Lectures 13 Volume Set.

Spain. Part 20

In one of the streets of this attractive city we were shown a little wine-shop, said to have been the home of the "Barber of Seville," whom the novel of Beaumarchais and the Opera of Rossini have made immortal. Unfortunately, however, no sooner had our carriage halted before it than we were surrounded by several of those beggars who are, in southern Spain especially, an intolerable nuisance. The Spaniards, in their grandiloquent form of speaking, have for these mendicants a particular formula, which is supposed to banish them as rapidly as Persian insect-powder does the pests of Spanish inns. They bravely address them with the words "Per done usted, por Dios, hermano!" [For God's sake, excuse me, brother!]. Guide-books recommend this phrase, and I tried it several times, but with no effect. When, therefore, my patience was exhausted, I usually fell back on the shorter and much more pointed remark of "Al d e m o n i o!" which at least relieved my feelings, for it means in plain English, "Go to the devil!"

Spanish Beggars.

Upon the bank of the Guadalquivir stands a conspicuous feature of Seville, known as the Tower of Gold. Originally a Moorish structure of defense, it was used by the Spaniards as the treasure-house, in which, amid the blare of trumpets and the enthusiastic shouts of the exultant populace, were stored the enormous quantities of gold brought by Columbus and other brave discoverers from the New World, and fondly deemed by Spain exhaustless. No doubt the memory of this brilliant tower lingered in the minds of Pizarro, Cortez, and Columbus long after their departure from Seville, and it formed as well the goal of their ambition when, after years of toil and conquest, they once more ascended the Guadalquivir with their precious spoils.

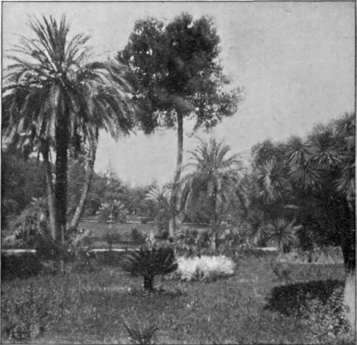

In The Grounds Of San Telmo.

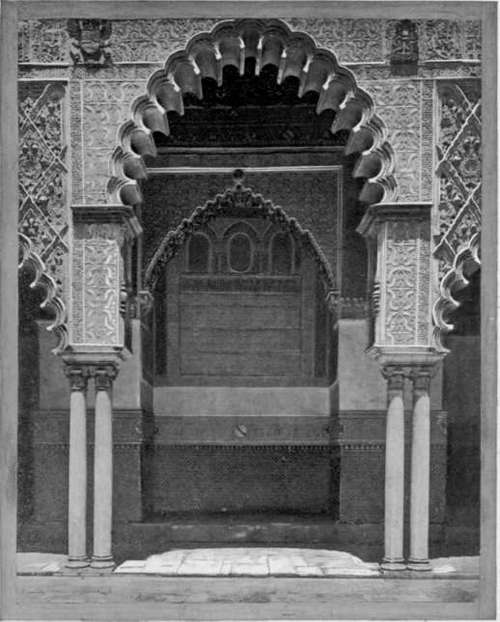

An Arch In The Alcazar Of Seville.

The gardens of San Telmo, as well as those of the Alcazar of Seville, are beautiful. Renewing the system of irrigation which the Moors brought to such perfection, the Spaniards have introduced into these parks the waters of the Guadalquivir and made of them a partial vision of the Orient. Here, as in several localities in southern Spain, we noted with especial pleasure the beautiful symbol of the East, - the tree of romance and poetry - the palm. Spain owes this also to the Moors; for the first palm-tree ever seen in Spain was planted at Cordova by Abd-er-Rah-man, who desired to have here a memorial of his much-loved Damascus. Truly, it is not strange that the palm-tree has been worshiped by the children of the sun; for it not only shelters them from the ardent heat, but gives to them, unasked, the most nutritious fruit, and, surviving through many generations, like a beneficent deity, waves over them its rustling boughs as if in constant benediction.

One of the most precious monuments of Moorish art in Spain is the Alcazar of Seville. When the Christians had driven the Moors from this city, the conquering monarchs took up their residence here; but when they wished to embellish and enlarge the palace they were too wise to employ their own architects for such a work, and accordingly, during a time of peace, sent to Granada for Moorish aid. How beautiful are the results of their labor! For one who has not seen the Alhambra, it is difficult to imagine anything more exquisite than this Alcazar of Seville. For, thanks to the skill and talent of these Moorish workmen, another Aladdin-like palace here sprang into existence, almost rivaling the Alhambra. Here, as there, one fancies himself in some enchanted palace, whose carved and colored walls resemble a continuous network of gold and lace. The arches in the courtyard, resting on marble columns, are beautifully carved and perforated, and glitter with gilding and brilliant colors. The doors, too, are of cedar-wood inlaid with pearl, and around the walls we see a continuous expanse of the unrivaled Moorish tiles. Moreover, unlike much of the Alhambra, which has fallen into ruin, this exquisite work has been so carefully restored that it now gleams with almost the same brilliancy and beauty as when it echoed to the footsteps of the Moors.

Continue to: