Proportion. Part 2

Description

This section is from the book "The Principles Of Interior Decoration", by Bernard C. Jakway. Also available from Amazon: The Principles of Interior Decoration.

Proportion. Part 2

The Corinthian column is still more slender in proportion, having a height of ten diameters or more. Its flutings are separated by fillets terminating in curved forms, its capitals richly embellished with rows of carved leaves and elaborately constructed ornament. Thus for the severity of the Doric and the svelte delicacy of the Ionic the Corinthian order substitutes a quality of richness and magnificence.

The changes exemplified by the Greek orders are characteristic of the development of all the arts. Always they emerge vigorous, forceful and austere; always they become more delicate, more elegant, more graceful; always in the end they achieve a style rich, pretentious and florid. The arts change with changes in society, and in the degree that they are real arts - that is, real expression, rather than a foolish striving to put new wine into old bottles - their works are adapted in proportion as in everything else to the needs and aspirations of the people who create them.

Figure 24. - The Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian columns.

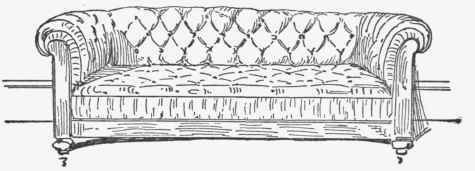

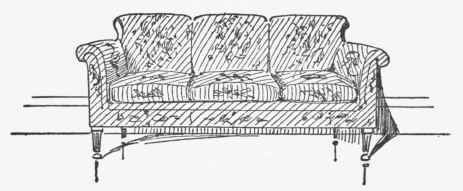

It is manifest, therefore, that excellence in proportion, like excellence everywhere else in interior decoration, is first of all a matter of fitness. We cannot use a Doric column in the architecture of a Louis XVI salon, nor can we use an over-stuffed sofa or a Renaissance table in its decoration. That is, we cannot use massive furniture, or large, heavy and strikingly ornamented accessories in a small room, or in any room which is designed to be dainty, gay or elegant. For just as the draft horse, beautiful as he strains at his load, would be absurd and ridiculous on the race course; and as the powerful shoulders and barrel-like chest of the wrestler would be unfitting and hence un-beautiful in the hurdler, so the proportions of a living room - using the term as defined to mean the adaptation of one part to the others and to the whole as respects magnitude, quality and quantity - could never be precisely the same as those of a drawing room, because these rooms do not have the same purpose or meet the same needs, and hence cannot have the same significance or express the same idea.

We have seen that the fundamental principle of decorative composition is to put together things which, either in appearance or in significance, are more or less alike. This principle conditions the choice not only of lines, colors, patterns and symbols, but also of shapes and sizes. All the parts of a furnished room must be congruous. That is, they must appear to the mind to have grown together in the process of expressing a common idea. Thus the idea of repose, for example, is as we have seen inevitably associated with horizontal as opposed to vertical extension. Accordingly the proportions of the room to be furnished, as well as of its principal decorative units, must reveal a marked emphasis upon length as opposed to height in the degree that an effect of repose is aimed at. Similarly, because the ideas of strength, heaviness, immobility, importance, permanence and dignity are inevitably associated with large size, the room itself and the important decorative elements used in it must be more or less large in the degree that these ideas are to be expressed, and more or less small in the degree that the ideas of delicacy, lightness, mobility, triviality, transience or grace are to be expressed.

Figure 25. - Note the change toward effects of lightness, delicacy, elegance, animation and gaiety with smaller size and more slender structural parts.

It is obvious that in setting about the creation of a room which shall adequately express a given emotional idea we must begin with the proportions of the room itself, since to select and arrange furniture characterized by horizontality in a room which was itself characterized by verticality could make only for confusion and ugliness. But while the decorator can determine the size and proportions of the units that he places in a given room, it usually happens in practice that he has nothing to do with the proportions of the room itself, but must take them as he finds them. When, as frequently happens, they do not accord with the motive of his projected treatment, he must either change his motive to fit the actual proportions of the room, or else he must change the apparent proportions of the room to fit his motive. That is, he must, through the employment of a variety of decorative artifices, increase or reduce the apparent height of the ceiling, make the room seem longer or shorter, wider or narrower, larger or smaller.

Let us take as an example the case of a living room which it is proposed to characterize by a marked effect of tranquillity and repose. Here, as always, the decorator will seek to achieve his purpose through a convergence of artistic effects. He will accordingly, other factors permitting, place a marked emphasis throughout (a) upon the unity as opposed to the diversity of the treatment; (b) upon low tones of color as opposed to high values; and (c) upon horizontal extension as opposed to vertical extension. A long low room, with broad windows and a wide fireplace, will of course present no difficulties. Where the ceiling is high, however, and the openings narrow, the room must be treated skillfully if the motive of repose is to be convincingly expressed. In such a room the ceiling must be brought down in appearance by the use of a color as dark as the lighting of the room will permit - preferably only a few tones lighter than the wall. A rough surface, like coarse canvas or sand-finished plaster, will help to bring down the ceiling, as will plaster relief or beaming. Reducing the amount of light thrown upon the ceiling through the use of direct light fixtures and of lamps properly shaded will have the same effect. Where there is no cornice the ceiling color may be carried down on the side walls to the height of the windows, or to a distance equal approximately to one-eighth of the total wall height, and its juncture with the wall color covered by a narrow molding. Horizontal divisions of the wall by a dado or frieze, or both, tend to reduce the apparent height of the ceiling, provided, of course, that the dominant lines of the frieze are horizontal or diagonal and not vertical. The walls can also be made to seem lower through the use of a paper or other wall fabric designed upon the circle or hexagon as a basis. The horizontal lines of the windows must be emphasized, usually by means of valances or lambrequins, and it will frequently be found desirable to extend the hangings a few inches beyond the casing on each side in order to increase the apparent width of the opening and thus to emphasize the horizontality of the treatment. The hangings should be caught back in order to break their straight vertical lines, which would tend to increase the apparent height of the room. Couches, tables, bookcases and other important objects will of course be relatively long and low, and vases, lamp-bowls and shades relatively wide and squat; while the rug, which to be most effective in a room of this sort ought to be relatively large and to approximate rather closely the proportions of the room, will be low in tone and either broken in hue or of thick pile or coarse texture in order to strengthen the base of the decorative treatment, and to emphasize the floor as opposed to the walls. In order to make the large pieces of furniture which are placed against the walls appear sufficiently high to harmonize with the proportions of the wall spaces and at the same time to preserve and emphasize their horizontality, it will be necessary to select pieces which are actually long as compared with their height, and then to place above them wide low pictures, mirrors, plastic friezes, or other similarly shaped elements. The mind, regarding each group of this sort as a unit, will be satisfied with the total height of the group as related to the wall height, while at the same time it will be strongly conscious of the dominant horizontal lines of the individual pieces. In this connection it is to be noted that because the eye moves more easily and quickly from side to side than up and down there is a constant tendency to overestimate the length of vertical as opposed to horizontal lines - a fact that the decorator must take into account in planning any treatment in which horizontals are to be emphasized.

Continue to: