Children. An Interview With Lady Henry Somerset

Description

This section is from "Every Woman's Encyclopaedia". Also available from Amazon: Every Woman's Encyclopaedia.

Children. An Interview With Lady Henry Somerset

Lady Henry Somerset is one of the most prominent of our social philanthropic workers, and as an authority on the subject of the welfare and training of girls, especially of those belonging to the educated classes, she has but few equals. To her efforts, the great Industrial Farm Colony at Duxhurst owes its inception, and for fifteen years she had a home for the training of workhouse children. She is also a prolific writer on the different phases of woman's work, while her labours in the cause of temperance are world-famous. In this interview-article, specially contributed to Every Woman's Encyclopaedia, Lady Henry gives most valuable criticism and helpful advice on the all-important subject of the future of the girlhood of this nation

The importance of this problem can scarcely be over-estimated. Our boys can, to a large extent, be depended upon to shape their own lives. They recognise that the choice of a suitable occupation, and success in that occupation, mean everything. It means happiness, and a foundation on which they can build a career and a home of their own. And the average parents may be said to make every endeavour to help their sons to that end.

But what of our girls - the mothers of the nation?

Alas, the majority of them seem to regard work and training after leaving school merely as an incident in their lives, as something which will keep them occupied and provide them with pin-money until an opportunity for marriage occurs. What is worse still, their parents, unconsciously, perhaps, foster this idea. They are apt to think - and these remarks apply particularly to the middle-class parent - that if a daughter can earn sufficient money to buy her dresses and hats, and seems happy and contented, there is no necessity to worry concerning her vocation or training. And thus the girl is allowed to drift.

"What would you like to do now?" the parents ask their daughter of fifteen or sixteen, who, perhaps, has just left a higher grade school, where she may have acquired, in addition to general knowledge, a smattering of music, art, and shorthand.

In nine cases out of ten, such a girl will wish for what some have termed a "genteel occupation" - that is, a post in an office as shorthand-typist, for instance; in a hospital

Children as nurse; or in a shop as a cashier or bookkeeper. Or, perhaps, she may sigh for the stage or the musical profession, or wish to dabble in art or journalism.

Suggest domestic training, and learning the art of housekeeping and cooking, and the idea is scouted. The average modern girl seems to have no taste for such work - menial work, she often terms it. Time enough for that when I am married, she thinks. She does not recognise that domesticity is the very foundation of her life-work and happiness. If she is to become a good and happy wife and mother, she must possess that knowledge. If she is to become a successful nurse, she must understand the art of attending to the creature comforts of others. If she wishes to become a school-teacher, a governess, or to go out to our Colonies and labour there, she will find that the surest way to success lies in a knowledge of the home.

There is no such thing as menial work, and I am afraid that mothers are often to blame for this wrongful notion possessed by many girls; for they fail to train them in early years to do their share of domestic work - work which it is imperative a daughter should do. Frequently I receive letters from mothers asking if I know of any opening or vacancy which would suit their daughters. And when I have made inquiries as to the capabilities of these daughters, I have often found that they could do nothing really well, not even make a bed or bake a cake. They could not cook, or lay a table, had very little idea of housekeeping - in fact, had no real practical knowledge whatever. Utter failure, of course, would be the result if such girls adopted the nursing profession, or went out to one of our Colonies to manage a home. Please do not misunderstand me. I do not wish to decry the present-day education of girls so far as school and colleges are concerned. But I do contend that if our daughters are to be successful and happy women, they must receive practical training in the various branches of home work.

This need not interfere with any other work for which they consider they have an aptitude. A girl can be a successful actress, author, or artist, and yet know how to cook a dinner properly, and keep household accounts. Study the lives of many prominent women of to-day, and you will find them extremely practical-minded women who have been brought up in the home by mothers who recognised that domestic training was essential to a girl's upbringing, and consequently they learnt to cook, sew, and manage household affairs long before they took up the special work which has brought their name before the public.

In lonely prairie regions of the Wild West, I have met women superintending the management of busy farms, while their husbands were away. They were extremely well-educated women, who had spent several years at college, and could talk on literature, art, and a dozen and one intellectual subjects. But they were far too broad-minded to regard domestic work as menial. Indeed, they took the greatest pride in the management of their homes, and knew every detail of household work. And this was because, from their earliest years, they had been taught by their mothers to take an interest in household management. I noticed recently, by the way, an interesting observation made by Miss Ada Crosby, the Lady Mayoress. Talking of thriftlessness, she said: "In my opinion, every woman, in whatever class of life, should undergo a thorough training in cookery, and no woman should be allowed to become a cook unless she held a certificate showing she was fully qualified."

I fully agree with this remark. We are the worst cooks in the world. There are no women in the world who prepare food so badly as the women in this country, and it is almost impossible to get a good cook at a reasonable wage. In France, cookery is a woman's art, and she can prepare the daintiest of dishes at the smallest possible cost. It seems to me that women in this country look upon cooking solely as a necessity, rather than pleasurable work, as they do abroad, and, consequently, girls are not enamoured with the idea of becoming cooks. And yet there are splendid openings for good women cooks, and excellent wages can be earned.

There is another point which should be borne in mind. If a girl does not understand the art of cooking and housekeeping, she can scarcely be expected to understand the art of shopping, or the value of money. Such a type of girl is not likely to make a success of life, no matter whether she marries or not. Perhaps I may be allowed to make a second reference to Miss Crosby's remarks, when she said:

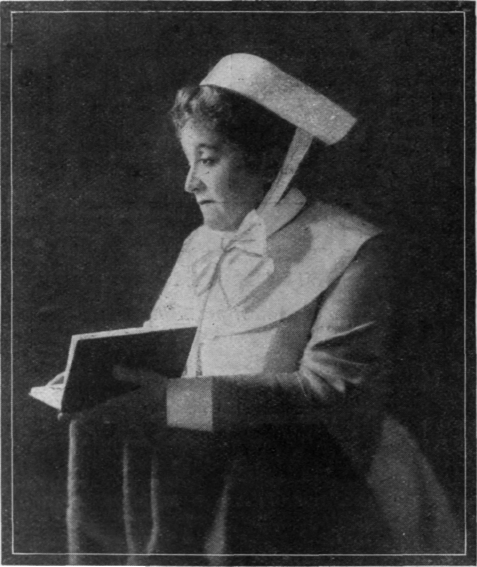

Lady Henry Somerset, a wellknown philanthropic worker on behalf of Photo, women and girls Robinson, Redhill

"Economical shopping is a study which many women neglect. They won't take the trouble to find out at which particular shop they can obtain the best value for their money. Instead of buying certain articles at certain shops, they prefer to get as many as possible at one shop, irrespective of the goods."

A Fatal Ignorance

This is quite true, but I think, more often than not, the cause of this bad shopping is to be found in the ignorance of such women - ignorance which arises from their lack of knowledge of household management.

I really think I would send a girl to the Colonies, where she would become more broad-minded, and get away from the idea that it is degrading to do this or that. She would learn that the Colonial girl does not understand this cant about superior work - that she first fits herself to become a good housewife and mother, and afterwards takes up any other work for which she may think she is fitted.

"Now I must leave you to attend to the kitchen," I have heard ladies of real refinement say on the other side, during a conversation on current events or literature, which showed their cultivation; and it is such women, who can combine real domesticity with social life and other work, who derive the greatest happiness and success.

Of course, it is not an easy matter to recommend any particular vocation to girls. Each must necessarily be guided by her own capabilities and circumstances. I certainly think, however, that there is a great opening for lady gardeners and lady farmers, but in such cases it is essential that a girl should possess a fairly strong constitution. Our experience at the Duxhurst Farm Colony proves that gardening can be made to pay if carried out on practical lines. But, of course, no girl should attempt to set up as a practical gardener until she has passed through a course of special training at one of the gardening colleges. I might mention, by the way, that there is a great demand for lady gardeners in Australia; greater, in fact, than in Canada.

The Nursing Profession

I have often been asked whether 1 would recommend nursing as a profession. I fear that the supply of nurses is far greater than the demand, and, moreover, the work is very hard. But I would not discourage any girl who has an aptitude for nursing. If she is skilful and determined, she will assuredly win her way. The same remark applies with equal force to other professions; but whether a woman decides to become a teacher, nurse, poultry farmer, gardener, a public health worker, a house decorator, a dentist, an artist, or a journalist - indeed, whatever occupation may be decided upon - I repeat that a preparation in domestic training is one likely to add to happiness and success.

Continue to: