Russia

Description

This section is from "The American Cyclopaedia", by George Ripley And Charles A. Dana. Also available from Amazon: The New American Cyclopædia. 16 volumes complete..

Russia

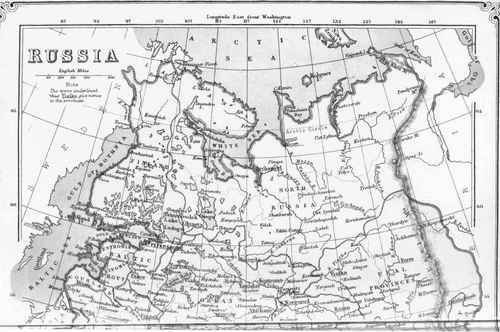

Russia (Russ. Rossiya), the largest connected empire of the world, extending, in Europe and Asia, from lat. 38° 20' to about 77° 30' N., and from lon. 17° 38' E. to about 170° W. It is bounded N. by the Arctic ocean, E. by the Pacific, S. by the Chinese empire, Independent Tur-kistan, Persia, Asiatic Turkey, and the Black sea, and S. W. and W. by Roumania, Austria, Prussia, the Baltic sea, and Sweden. Its greatest length from W. to E. is about 6,000 m.; its greatest breadth (exclusive of islands) about 2,300 m. Its total surface is estimated to comprise one twenty-sixth of the entire surface of the globe, and to represent one sixth of its firm land. The natural geographical advantages of Russia are very great. The first trade with England began at the port of Archangel on the White sea. Now the maritime trade of the empire has its chief emporiums on the Baltic, the Black and Caspian seas, and the inlets of the northern Pacific. The N. coast is deeply penetrated by large arms of the Arctic ocean, forming gulfs, of which those of Obi and Kara, on the border of Europe and Asia, and on the N. W. the White sea, are the most important. - The rivers of Russia are numerous and remarkable for their magnitude.

Those of European Russia (to which alone we mainly restrict the descriptive portions of this article, referring the reader for Asiatic Russia to the articles Caucasus, Siberia, and Turkis-tan) belong to the four great basins of the Arctic ocean, the Baltic, the Black sea, and the Caspian sea. The great watershed is formed by a broad central ridge, commencing on the frontiers of Poland, stretching across the empire in an irregular waving line, and terminating on the W. side of the Ural mountains. The waters N. of this shed fall into the Arctic ocean and the Baltic sea, those S. of it into the Black or the Caspian. The Arctic ocean receives directly the Petchora, which rises in the Ural mountains, traverses the most deserted parts of Russia, receives several tributaries, and discharges by a wide estuary, remarkable for the number of its islands. Through the White sea, the Arctic ocean receives the Me-zen, the Dwina, and the Onega. On the declivity of the Baltic are the Tornea and the Kemi, which fall into the gulf of Bothnia; the Neva and the Narva, which fall into the gulf of Finland; the Düna and the Aa, which flow into the gulf of Riga; and the Niemen, which rises in the government of Minsk, and before terminating its course enters Prussia under the name of the Memel. The Vistula, whose source and mouth belong to Austria and Prussia respectively, traverses Poland, and receives several tributaries, among which the Bug, rising in Galicia, Austria, is most important.

To the basin of the Black sea belong the Pruth and the Dniester, both rising in Galicia; the Bog, rising in Podolia; the Dnieper, which rises in the government of Smolensk, receives a considerable number of affluents, among them the Beresina, and falls into the Black sea near Kherson; the Don, originating in the government of Tula, intersecting the Cossack country, and discharging into the sea of Azov; and the Kuban, which descends from the Caucasus, forms part of the boundary between Asia and Europe, and near its mouth separates into two branches, one of which falls into the sea of Azov and the other into the Black sea. The basin of the Caspian sea receives the Volga, the largest river of Europe, which rises in the government of Tver and discharges into the Caspian near Astrakhan, and the Ural, which descends from the eastern declivity of the mountains, traces out for some distance the frontier of Europe, and falls into the Caspian near Guriev. Most of the lakes of European Russia belong to the northern basins, as Lake Ladoga, the largest lake of Europe, and Lakes Onega, Peipus, and Ilmen. The government of Olonetz alone contains hundreds of small lakes, and a still larger number is found in Finland. - European Russia in general forms part of an immense plain, beginning in Holland, and extending over the north of Germany and the whole east of Europe. Only occasionally small table lands occur, as the Valdai hills* in the governments of Novgorod and Tver, the loftiest summit of which is about 1,150 ft. high.

To the northwest some branches of the Scandinavian mountains enter the Russian territory. In the southwest the Carpathian mountains send forth slight ramifications. To the south, in the peninsula of the Crimea, is the insulated chain of the Yaila mountains, which in one place attain an elevation of about 5,000 ft. To the east the Ural mountains, and to the southeast the Caucasus, form in great part the natural frontier between Europe and Asia. The plains are here and there covered with swamps, more frequently with forests; while in the southern parts of the empire they consist of dry and woodless tracts called steppes. The steppe region extends from the river Pruth, across the lower watercourses of the Dniester, Bog, Dnieper, and Don, as far as the Volga and Caspian sea. It is only in the western and middle parts of this region that rich meadow land is met with; the rest is poorly watered, thinly populated, and, notwithstanding the occasional fertility of the soil, but little favorable to agriculture. What the steppes are to the south and east of Russia, the tundras in the governments of Olonetz and Archangel, mostly toward the shores of the Arctic ocean, are to the north.

They are treeless wastes, bearing a scanty vegetation of low shrubs on a moss or turf surface. - The geological structure of European Russia is characterized by vastness and simplicity. Single formations are found to extend over entire provinces. In the northern part the granite and the Permian formation, composed of grits, marls, conglomerates, and limestones, prevail; Esthonia and Ingria (government of St. Petersburg) present the Silurian formation, resting on schistose rocks. Along the chain of the Ural mountains, besides the eruptive formations of the most ancient period, the Silurian group prevails. Lithuania and Poland belong almost wholly to the tertiary group; they also contain cretaceous rocks. The southern portion of European Russia belongs to the tertiary and granitic groups. The southern coast of the Crimea is of Jurassic formation. In the Caucasian countries cretaceous and Jurassic rocks prevail, mixed with granite. - The quality of the soil differs very greatly in the different provinces. Some consist mostly of sandy barren plains or vast morasses.

The most valuable portion of the empire is that south of the Valdai hills and of Moscow, extending on the east to the Volga, and including the country of the Don almost as far as the sea of Azov, and on the west to the frontier of Galicia. All this region is rich wheat land, exporting wheat to Asia and Europe, through Odessa, Nikolayev, Taganrog, and Kertch. - Almost the whole of European and three fourths of Asiatic Russia lie within the temperate zone. The southern border of the empire approaches to within 15° of the tropic zone, while the northern border extends 11° beyond the arctic circle. In general the climate is severe. The mean temperature of winter passes the freezing point even in the most southern districts. South of lat. 58° the mean temperature is between 40° and 55° F.; the winters are long and severe, and the summers short and hot. With lat. 58° the cold region begins, and with lat. 65° the arctic region. At St. Petersburg, which is within the former space, the thermometer in December and January sinks to 20° or 30° below zero, and exceptionally much lower, while in the summer it rises to 85° or 90°. Among the most common atmospheric phenomena, in the steppes as well as in the northern provinces and in Siberia, is the buran, a vehement wind accompanied by heavy falls of snow.

The central part is also subject to violent snow storms, called viuga. In general, the climate is healthy. - The official census in Russia is taken once in nine years, and the last was in 1867. More recent estimates of the population of portions of the Russian possessions have been made for 1870, 1871, and 1872, and printed in the St. Petersburg "Calendar" (1875) and other publications. The following tables of areas and population are from Behm and Wagner's Bevölkerung der Erde, annexed to Petermann's Geographische Mittheilungen for 1875. The areas are Strelbitzki's recent calculations approved by the government and dated 1875. They include the newly acquired Transcaspian province and the Amoo Darya district organized in 1874, with the areas and population of that year. The populations here given in Russia proper, Poland, Siberia, and Central Asia are for 1870; in the Caucasus for 1871; and in Finland for 1872. The Russian empire is divided into governments (and a few divisions differently designated), the area (including inland waters) and population of each of which are estimated as follows:

GOVERNMENTS. | Area in sq. m. | Population. |

RUSSIA PROPER. | ||

1. Archangel.............................................. | 331,503 | 281,112 |

2. Astrakhan.............................................. | 86,668 | 601,514 |

3. Bessarabia............................................. | 14,046 | 1,078,932 |

4. Courland............................................... | 10,537 | 619,154 |

5. Don Cossack territory........................... | 61,911 | 1,086,264 |

6.Esthonia.................................................. | 7,818 | 323,961 |

7. Grodno................................................... | 14,965 | 1,008,521 |

8. Kaluga................................................... | 11,938 | 996,252 |

9. Kazan..................................................... | 24,600 | 1,704,624 |

10. Kharkov................................................. | 21,040 | 1,698,015 |

11. Kherson................................................. | 27,522 | 1,596,809 |

12. Kiev....................................................... | 19,686 | 2,175,132 |

13. Kostroma............................................... | 32,700 | 1,176,097 |

14. Kovno.................................................... | 15,692 | 1,156,041 |

15. Kursk..................................................... | 17,936 | 1,954,807 |

16. Livonia................................................... | 18,158 | 1,000,876 |

17. Minsk..................................................... | 35,272 | 1,182,230 |

18. Mohilev.................................................. | 18,550 | 947,625 |

19. Moscow.................................................. | 12,857 | 1,772,624 |

20. Nizhegorod............................................. | 19,795 | 1,271,564 |

21. Novgorod............................................... | 47,234 | 1,011,445 |

22. Olonetz..................... | 57,436 | 296,392 |

23. Orel........................ | 18,040 | 1,596,881 |

24. Orenburg............................................... | 73,885 | 900,547 |

25. Penza..................................................... | 14,996 | 1,173,186 |

26. Perm...................................................... | 128,246 | 2,198,666 |

27. Podolia.................................................. | 16,222 | 1,933,188 |

28. Poltava................................................... | 19,264 | 2,102,614 |

29. Pskov....................... | 17,068 | 775,701 |

30. Riazan.................................................... | 16,253 | 1,477,433 |

31. St. Petersburg........................................ | 20,760 | 1,325,471 |

32. Samara.................................................. | 60,197 | 1,837,081 |

33. Saratov.................................................. | 32,622 | 1,751,268 |

34. Simbirsk................................................ | 19,108 | 1,205,881 |

35. Smolensk............................................... | 21,637 | 1,140,015 |

36. Tambov................................................. | 25,683 | 2,150,971 |

37. Taurida.................................................. | 24,537 | 704,997 |

38. Tchernigov............................................ | 20,231 | 1,659.600 |

39. Tula......................... | 11,955 | 1,167,878 |

40. Tver......................... | 25,223 | 1,528,881 |

41. Ufa......................... | 47,031 | 1,364,925 |

42. Viatka...................... | 59,114 | 2,406,024 |

43. Vitebsk...................... | 17,438 | 888,727 |

44. Vladimir................................................ | 18,862 | 1,259,923 |

45. Volhynia.................... | 27,738 | 1,704,018 |

46. Vologda................................................. | 155,498 | 1,003,039 |

47. Voronezh............................................... | 25,437 | 2,152,696 |

48. Wilna........................ | 16,411 | 1,001,909 |

49. Yaroslav.................... | 13,750 | 1,000,748 |

50. Yekaterinoslav........................................ | 26,146 | 1,352,300 |

Total Russia proper (inclu-ding inland waters)...... | 1,881,216 | 65,704,559 |

GOVERNMENTS. | Area in sq. m. | Population. |

POLAND. | ||

1. Kalisz....................................................... | 4,392 | 669,261 |

2. Kielce....................................................... | 3,897 | 518,780 |

3. Lomza...................................................... | 4,667 | 489,699 |

4. Lublin...................................................... | 6,501 | 707,098 |

5. Piotrków.................................................. | 4,729 | 682,495 |

6. Plock........................................................ | 4,200 | 471,938 |

7. Radom..................................................... | 4,769 | 532,466 |

8. Siedlce..................................................... | 5,534 | 504,606 |

9. Suwalki.................................................... | 4,846 | 524,489 |

10. Warsaw.................................................... | 5,622 | 925,639 |

Total Poland......................................... | 49,157 | 6,026,421 |

Total Russia in Europe with Poland................. | 1,944,615 | 71,730,9S0 |

FINLAND. | ||

1. Abo-Björneborg...................................... | 9,332 | 306,331 |

2. Kuopio..................................................... | 16,498 | 226,130 |

3. Nyland................................................... | 4,584 | 173,141 |

4. St. Michael.............................................. | 8,819 | 159,348 |

5. Tavastehuus............................................ | 8,324 | 193,477 |

6. Uleaborg................................................. | 63,955 | 185,890 |

7. Vasa........................................................ | 16,146 | 310,987 |

8. Viborg..................................................... | 16,611 | 276,884 |

Total Finland....................................... | 144,269 | 1,832,138 |

THE CAUCASUS. | ||

1. Stavropol................................................. | 26,634 | 437,118 |

2. Kuban..................................................... | 37,169 | 672,224 |

3. Terek...................................................... | 23,268 | 485,237 |

4. Daghestan............................................... | 11,520 | 448,299 |

5. Zakatal..................................................... | 1,620 | 56,802 |

6. Tiflis........................................................ | 15,614 | 606,584 |

7. Baku........................................................ | 15,151 | 513,560 |

8. Elisabethpol............................................. | 17,117 | 529,412 |

9. Erivan...................................................... | 10,668 | 452,001 |

10. Kutais...................................................... | 7,995 | 605,691 |

11. Sukhum.................................................... | 3,332 | 70,701 |

12. Tchernomore........................................... | 2,749 | 15,703 |

Total Caucasus................................... | 172,837 | 4,893,332 |

SIBERIA. | ||

1. Littoral province (Pacific)..................... | 731,917 | 45,000 |

2. Amoor.................................................. | 173,554 | 44,400 |

3. Transbaikal........................................... | 240,772 | 430,780 |

4. Irkutsk..................... | 309,180 | 378,244 |

5. Yakutsk ................................................ | 1,517,077 | 231,977 |

6. Yeniseisk............................................... | 992,838 | 372,862 |

7. Tomsk...................... | 329,027 | 838,756 |

8. Tobolsk.................................................. | 531,964 | 1,086,848 |

Total Siberia......................... | 4,826,329 | 3,428,867 |

CENTRAL ASIA. | ||

Kirghiz Territories. | ||

1. Akmolinsk............................................. | 210,558 | 381,900 |

2. Semipolatinsk........................................ | 188,298 | 510,163 |

3. Turgai.................................................... | 202,186 | 289,930 |

4. Uralsk.................................................... | 141,469 | 346,715 |

5. Transcaspian Province.......................... | 126,282 | 275,000 |

Turkistan. | ||

1. Semirietchensk...................................... | 156,292 | 543,094 |

2. Kulja...................................................... | 27,496 | 114,337 |

3. Sir Darya............................................... | 165,998 | 848,489 |

4. Zerafshan............................................... | 19,665 | 271,000 |

5. Amoo Darya.......................................... | 39,957 | 220,000 |

Total Central Asia............................... | 1,277,196 | 3,800,628 |

RECAPITULATION. | ||

Russia in Europe......................................... | 1,881,216 | 65,704,559 |

Poland, Kingdom of.................................... | 49,157 | 6,026,421 |

Finland, Grand Duchy of............................ | 144,269 | 1,832,138 |

The Caucasus.............................................. | 172,837 | 4,893,332 |

Siberia.......................................................... | 4,826,329 | 3,428,867 |

Central Asia................................................. | 1,277,196 | 3,800,628 |

Grand total............................................ | 8,351,004 | 85,685,945 |

Russia proper is divided by geographers into Great Russia, embracing the central and northern governments (the latter also designated North Russia) from Kursk and Voronezh to Archangel, and including what was formerly known as Muscovy, from its centre Moscow; Little Russia, or Ukraine (Kiev, Tchernigov, Poltava, and Kharkov); South Russia or New Russia, comprising Bessarabia, Kherson, Tau-rida, Yekaterinoslav, and the territory of the Don Cossacks; West Russia, comprising Lithuania, Volhynia, Podolia (part of Red Russia, the bulk of which is in Galicia), Vitebsk and Mohilev (White Russia), and Minsk (Black Russia); the Baltic provinces, comprising Cour-land, Livonia, Esthonia, and St. Petersburg (Ingria); the Volga provinces; and the Ural provinces. The census of Russia for 1722 gave 14,000,000 inhabitants; that of 1815, 45,000,-000; that of 1835, 55,000,000; and that of 1851, 65,200,000. But the data of the censuses of former times were very imperfect, and conquests have greatly swollen the total of nearly every census since 1722. For the years 1860 to 1865 the number of births was on an average a little above 3,000,000 a year, the number of deaths about 2,000,000, and the average yearly increase of the population was estimated at 1 1/3 per cent.

The number of illegitimate births is given at 90,000 a year, and the excess of females over males in the population is estimated at 750,000. In European Russia the average density is about 35 inhabitants to the square mile; in Asiatic Russia the average does not reach 2 to the square mile. St. Petersburg and Moscow, the present and former capitals of the empire (the latter, however, still ranking as capital for some purposes), have respectively 667,026 (1869) and 611,970 (1871) inhabitants. Only four other cities have more than 100,000, viz.: Warsaw, 279,502 (1873); Odessa, 162,814(1873); Kishenev, 103,998 (1867); and Riga, 102,043 (1867). Of the other cities and towns, 8 number from 50,000 to 100,000. - Although many portions of the empire in point of productiveness compare favorably with the most fruitful countries in Europe, agriculture is generally still at a low stage; the government and proprietors of large estates, however, have of late done much to improve it, and agricultural machines are largely imported from the United States. The wealth of the landed proprietor formerly consisted less in the extent of his land than in the number of serfs attached to it.

The best cultivated land is to be found in the southern portion of the Baltic provinces, in the governments near Moscow, and in Poland; but even in these most favored provinces there are many uncultivated tracts of land. According to Lengenfeldt (Russland im neunzehnten Jahrhundert, Berlin, 1875), in European Russia, 20.3 per cent. of the entire surface is arable land, 11.8 meadows, 40.5 forests, and 27.4 pastures and uncultivated land. The arable land amounts to 20.9 per cent. in Russia proper, 50 in Poland, and only 1.2 in Finland. The forests cover 40.3 per cent. in Russia proper, 25.20 in Poland, and 53.3 in Finland. The forests formerly constituted an inexhaustible source of riches, but from reckless administration they now produce comparatively little. The old three-field system of husbandry, by which one third of the land is always in fallow, is still in general use; and in Great and Little Russia, owing to the depth of the soil, no manure is necessary. All the cereals are produced in such abundance as to leave a large surplus for export. Maize is chiefly grown in the countries about the Black sea; flax, hemp, and hops are of excellent quality; the potato is grown in all parts of the empire.

The cultivation of the beet root has been greatly advanced, and a large number of sugar houses are already supplied by it. The culture of the vine in the Crimea, Bessarabia, and other southern provinces furnishes an average of 54,000,000 gallons, valued at 11,610,000 rubles. Tobacco is grown on theVolga, in Little Russia, and on the Don, and yields annually about 70,000,000 lbs., of which about live sixths belongs to Bessarabia, Poltava, Tchernigov, and Samara. Horticulture, except in the vicinity of the great cities, is neglected. Of late many agricultural societies have been formed, and a number of schools established. - Horses are very numerous in Russia, and highly valued. In the S. W. provinces the breed is particularly fine. In general the horses of Russia are hardy and strong, but not so well taken care of as in other countries. The best studs are in the governments of Tambov, Kharkov, Voronezh, and Kiev. Russia sells a large number of horses annually to Austria and Prussia. The breeding of sheep is very extensive; the wool of the common Russian sheep is hard and coarse, but of late years the breeding of fine-wooled sheep has been steadily on the increase, especially in the Baltic provinces, in Poland, and in the southern governments.

Hogs are most abundant in Great Russia, Lithuania, and throughout the western provinces. The number of domestic animals in 1874, according to the reports of the statistical central committee of St. Petersburg, was about 20,000,000 horses, 28,500,000 horned cattle, 64,500,000 sheep, and 11,000,000 swine. Of the sheep about 14,000,000 were of the fine-wooled sort, principally found in the governments of Yekaterinoslav, Kherson, and Bessarabia (about 7,000,000). Bee culture is most extensive in Poland, the Lithuanian governments, and those on the Volga, especially Nizhegorod, Kazan, and Simbirsk; altogether it yields annually about 7,000,000 lbs. of wax and 21,000,000 lbs. of honey, and leaves considerable surplus for exportation. The culture of silkworms was introduced by Peter the Great, and was especially developed in the government of Astrakhan and in the southern part of the Crimea. Since 1864 it has greatly suffered by a disease among the silkworms. The southern provinces yield an annual average of nearly 20,000 lbs.; in Transcaucasia silk to the amount of about 4,000,000 rubles has been produced annually.

Reindeer are kept N. of lat. 66°, and camels in the south, many being found near Orenburg. Among the wild animals are the aurochs (in the forest of Bialovitza in Lithuania), elks, deer, bears, wild hogs, gluttons, wolves, foxes, and saiga antelopes. Furs are an important article of export. Fish is very abundant in the Polar sea and in the rivers, and some tribes, especially in the northeast, live entirely by fishing. The most important fisheries are those of the Volga, the Ural, and the sea of Azov. - Nearly all the metals are found in Russia, most of them of excellent quality. The principal mines are in the Ural and Altai mountains, and near Nertchinsk in Siberia. The produce of gold increased from 18,900 lbs. avoirdupois in 1839 to 49,800 in 1845, and 65,700 in 1847, since which it has again decreased, being 61,700 lbs. in 1869. Silver is also found in the Ural and Altai mountains; the produce in 1869 amounted to 39,300 lbs. Platinum is found almost exclusively in the neighborhood of Yekaterinburg. It was first discovered in 1823; in 1861 the produce was 8,060 lbs.

Copper is found in the Ural, but much more copiously (though as yet but little worked) in E. Siberia. The produce was 3,555 tons (of 2,240 lbs.) in 1852, 5,441 in 1857, and 4,310 in 1868. The iron mines furnish more than enough for the wants of the empire. The works in the Ural mountains alone are said to employ above 50,000 laborers. The total produce was 167,214 tons in 1852, 205,822 in 1857, and 319,000 in 1868. Rich coal mines have been discovered in nearly all the southern provinces of the empire, and the annual produce is rapidly increasing, amounting in 1868 to 402,300 tons. The country is very rich in salt and brine springs, the most important of which are in the government of Taurida, which alone furnishes annually about 250,000 tons, while the total produce in 1868 was 538,800 tons. - Manufactures are increasing with wonderful rapidity. Their introduction into Russia began in the 15th century, but very little was done until the time of Peter the Great. Catharine II., Alexander I., Nicholas I., and Alexander II. have all distinguished themselves by zeal in encouraging manufactures.

At the death of Peter the Great there were 21 large imperial manufactories, and several smaller ones; in 1820 their number had risen to 3,724, in 1837 to 6,450, in 1845 to 7,315, and in 1854 to 18,100. Later statements vary widely. According to Sarauw (Das Russische Reich in seiner Jinanziellen und ökonomischen Entwickelung, etc., Leipsic, 1873) and Lengenfeldt, the total number of factories in 1866, inclusive of distilleries and breweries, large and small, was 84,944, which employed 919,025 workmen, and the value of their products was 650,000,000 rubles. The chief seat of manufactures is Moscow, and next the governments of Vladimir, Nizhegorod, and Saratov, and St. Petersburg and Poland. Among the most important products are woollen goods, silk, cotton, linen of all kinds, leather, tallow, candles, soap, and metallic wares. Cotton spinning is developing rapidly; in 1870 about 122,000,000 lbs. of raw cotton were imported, while 106 spinning mills yielded about 8,000,000 lbs. of yarn, not sufficient, however, for the domestic looms, which in 1,508 manufactories produced about 220,000,000 rubles worth of cotton goods. The manufacture of woollen goods is likewise rapidly gaining. In 1866, 1,831 manufactories employed 105,135 workmen, and produced goods valued at 63,-000,000 rubles.

The manufacture of mixed woollen goods began in 1840, and in 1845 Moscow alone had 22 establishments; the number of manufactories in 1870 was 33, and the aggregate value of the goods produced was 1,500,-000 rubles. The chief seat of the silk manufacture is the government of Moscow; altogether there are 518 establishments, employing 12,000 workmen. The number of beet-sugar manufactories in 1871 was 325, which employed 70,000 persons; the produce was valued at 30,000,000 rubles. - The seaports are few, being almost confined to Archangel on the White sea, St. Petersburg and Riga on the gulfs of the Baltic, Odessa, Nikolayev, and a few others on the Black sea, Taganrog on the sea of Azov, Astrakhan, Baku, and Kizliar on or near the Caspian, and Nikolayevsk at the mouth of the Amoor. The principal articles of the foreign commerce for 1871-'2 were:

EXPORTS. | Rubles. |

Cereals................... | 134,600,000 |

Flax........................ | 37,900,000 |

Flax seed................ | 22,300,000 |

Wool...................... | 14,500,000 |

Tallow.................... | 2,900,000 |

Timber................... | 22,400,000 |

Hemp..................... | 11,900,000 |

Hogs' bristles......... | 5,700,000 |

Cattle..................... | 10,200,000 |

Tow....................... | 2,800,000 |

Hides..................... | 3,300,000 |

Cordage................. | 1,500,000 |

Furs........................ | 3,200,000 |

IMPORTS. | Rubles. |

Raw cotton............. | 46,900,000 |

Hardware..... | 20,400,000 |

Machines................ | 29,500,000 |

Tea......................... | 35,200,000 |

Raw metals............ | 24,600,000 |

Dyestuffs............... | 14,900,000 |

Oils............................. | 12,600,000 |

Liquors.................. | 14,300,000 |

Wool...................... | 15,200,000 |

Fruit.......... | 11,300,000 |

Woollen goods....... | 14,200,000 |

Cotton yarn............ | 12,600,000 |

Tobacco................. | 9,900,000 |

Raw silk...... | 6,500,000 |

Silk goods............... | 7,100,000 |

The value of Russian commerce for 1872 was:

EUROPEAN AND AMERICAN TRADE. | Imports, rubles. | Exports, rubles. |

Germany....................................................... | 171,328,000 | 77,319,000 |

Great Britian................................................. | 120,067,000 | 143,306,000 |

France........................................................... | 18,890,000 | 22,331,000 |

Austro-Hungarian monarchy........................ | 23,786,000 | 19,559,000 |

Turkey.......................................................... | 18,709,000 | 6,028,000 |

Belgium........................................................ | 5,251,000 | 6,907,000 |

Netherlands.................................................. | 5,338,000 | 7,487,000 |

Italy.............................................................. | 12,773,000 | 8,980,000 |

Spain............................................................ | 1,548,000 | 109,000 |

Sweden and Norway.................................... | 4,423,000 | 5,442,000 |

Denmark....................................................... | 404,000 | 6,802,000 |

Greece.......................................................... | 2,411,000 | 1,235,000 |

Roumania..................................................... | 4,092,000 | 2,868,000 |

Portugal........................................................ | 485,000 | 570,000 |

United States................................................ | 12,295,000 | 1,078,000 |

Other countries............................................. | 12,878,000 | 1,582,000 |

Total....................... | 414,678,000 | 311,553,000 |

ASIATIC TRADE. | Imports, rubles. | Exports, rubles. |

Turkey......................................................... | 6,275,000 | 3,552,000 |

China........................................................... | 8,015,000 | 2,825,000 |

Persia................................................................................. | 4,925,000 | 1,693,000 |

Other countries............................................ | 20,000 | 1,262,000 |

Total....................... | 19,235,000 | 9,382,000 |

The following table gives the value of imports and exports for a series of years:

YEARS. | Imports, rubles. | Exports, rubles. |

1860.................... | 181,383,281 | 159,303,405 |

1865.................... | 209,247,777 | 164,305,010 |

1868.................... | 323,451,000 | 428,959,000 |

1870.................... | 342,853,000 | 318,510,000 |

1871.................... | 360,367,284 | 352,578,686 |

1872.................... | 242,320,000 | 272,870,000 |

In 1872 the imports of gold and silver, in coin and bars, amounted to 12,968,000 rubles, and the exports to 5,742,000. The movements of shipping in 1871 and 1872 were as follows:

YEARS. | ENTERED. | CLEARED. | ||

Vessels. | Tonnage. | Vessels. | Tonnage. | |

1871....... | 12,256 | 1,894,830 | 12,172 | 1,897,638 |

1872...... | 10,071 | 1,577,489 | 10,044 | 1,579,294 |

The Russian commercial fleet in 1874 comprised 2,504 vessels (of which 227 were steamers), of 520,584 tons. The inland trade is carried on in a very great measure by means of annual fairs, of which those at Nizhni Novgorod are the most remarkable. - The first railway in Russia was completed in 1836, and extends from St. Petersburg to Tzarskoye Selo and Pavlovsk, two imperial residences, the latter distant from the capital 17 m. A much more important road, from St. Petersburg to Moscow, was opened in 1851, and is 398 m. long. In 1874 the total length of the Russian railways was 10,725 m., with about 2,400 m. in course of construction. The aggregate capital expended in the construction of railways up to January, 1874, was 1,403,900,000 rubles. The interest guaranteed by the state amounted in 1873 to 51,180,000 rubles, of which 14,590,-000 had really to be paid. The entire receipts of the railways in 1873 amounted to 122,880,-000 rubles. The first electric telegraph was constructed in 1853, since which time the lines have been rapidly extended throughout the empire, including one across Siberia. The aggregate length of the lines at the close of 1872 was 44,692 m., and of telegraph wires 90,430 m.

The number of offices was 1,333, and of telegrams 3,259,552; the revenue, 17,120,000 rubles; expenses, 14,957,000 rubles. The Baltic is connected with the Black sea by the Düna, the Oginski canal, the Beresina, and the Dnieper and Bog systems, and with the Volga and the Caspian sea by the Nizhni Volo-tchok, Tikhvin, and Maria canals. A canal across N. Finland forms a connection between the White sea and the Baltic. Many other canals connect two rivers. The Don and the Volga are connected by a horse railroad. The communication with Siberia is greatly facilitated by natural waterways. The Kama and its affluent the Ufa lead close to the mines of the Ural. - The government of the Russian empire is an absolute monarchy. The emperor has the title of samoderzhetz (autocrat) of all the Russias. At the same time he bears the titles of king of Poland, grand duke of Finland, czar of Kazan, Astrakhan, and Siberia, and several others, including many hereditary German ones which have come to him through the connection of the Romanoff dynasty with German princely houses.

According to the law of 1797, the crown was hereditary by right of primogeniture, with a preference for the male descendants; but the emperor Nicholas changed this law, excluding female inheritance altogether so long as there is a male member of the family. All the marriages of the members of the reigning family must have the emperor's sanction, and all the children of a matrimonial alliance not recognized by the sovereign are excluded from the succession. The hereditary grand duke becomes of age at 16; all the other princes at 18. With regard to Finland, the emperor is bound by the act of incorporation of 1809 to observe certain constitutional privileges of the grand duchy; but in reality this is never done, and the kind of diet which Finland possesses is of no value to its people. The highest consultative body of the empire is the state council, which is frequently presided over by the emperor himself. It consists of the ministers and such other dignitaries as he may appoint, and is divided into three departments, legislative, administrative, and financial. The next in importance among the central boards of the empire is the senate, created in 1711 by Peter the Great. It has charge of the promulgation and execution of the law, and forms also the supreme court.

The number of its members generally does not exceed 120. The third central body is the holy synod, which has jurisdiction over the affairs of the Russian state church. The synod was established in 1721, and has its seat at St. Petersburg, with a section at Moscow. The state ministry consists of ten ministers, and a department of general financial control. There is also an institution called the committee of ministers, in which all the ministers meet once a week and consult on the affairs of the state, under the presidency of a dignitary specially appointed by the emperor. The ten ministers are those of the imperial house, of foreign affairs, of war, of the navy, of the interior, of finance, of public instruction, of justice, of the imperial domain, and of public works. Poland and Finland are represented at St. Petersburg by special secretaries of state, through whom all orders issuing from the central power are transmitted. The Caucasus, Siberia, and central Asia are ruled by their respective governors general, who have all the powers of imperial lieutenants. The division of the empire into governments is purely administrative. The officials at the head of them are called civil governors, but many of them are military men.

They all have above them general governors, who are invariably military men. These general governors are not dependent on the minister of the interior, but make their reports directly to the senate and the war office, and can be appointed and dismissed only by the emperor. There are 14 military general governorships of this description, viz.: those of St. Petersburg, Finland, Wilna, Warsaw, Kiev, Odessa, Kharkov, Moscow, Kazan, the Caucasus, Orenburg, West Siberia, East Siberia, and Tur-kistan. The judiciary system of Russia was entirely reorganized by a ukase of 1864. The courts are divided into two classes, courts of justices of the peace, with jurisdiction of civil cases not involving more than 500 rubles, and the general courts, consisting of the district courts and the courts of appeal. The decision of a justice of the peace can be. appealed from to the assembly of all the justices of a given district, the senate remaining in all cases the highest court of cassation. The trial of criminal causes by jury was introduced in 1866. - No empire of the world contains so great a variety of nations and tribes as Russia; their number exceeds 100, and they speak more than 40 different languages.

The smaller and the uncivilized tribes are rapidly being amalgamated with the ruling race, the Russians; but the Poles, the Lithuanians, the German element in the Baltic provinces, the Finns, and a few minor nationalities, do not yet give any indications of losing their distinct national character. The immense majority of the population are Slavs, in two principal divisions, Russians (56,600,000) and Poles (4,800,000), to which, as a third, though much smaller division, the Serbs and Slavic Bulgarians must be added, counting together about 70,000 souls, and mostly living in settlements on the Dnieper and the Inguletz. The Russians form almost the sole population of Great and Little Russia, and also preponderate in influence, if not in number, in South and West Russia and in the Volga and Ural provinces. The Russians are again subdivided into Great and Little Russians. The latter, also called Red Russians, Ruthenians, or Russins, include a large portion of the Cossacks, and inhabit Little Russia and South Russia, and, mixed with Poles, some districts of West Russia. The Great Russians are the predominant race, and their language is used throughout the empire by the government and the majority of the nation.

The common people are vigorous and hardy, accustomed to the rigors of a severe and varying climate, and the hardships entailed by oppression, a merciless conscription, and occasional famines. They are of a cheerful temper, fond of song and frolic, and addicted to excessive drinking. Though slavish, resigned, and generally good-natured, they are not unapt to fly into passion and commit acts of revenge, and both murder and arson are frequent. Theft is very common. They are both gregarious and migratory in their habits, easily adapting themselves to changed circumstances, and are possessed of unusual mechanical skill. As soldiers they are remarkable for endurance and blind obedience rather than for personal courage. The use of vapor baths is general, though cleanliness is far from being a national virtue. Gross superstition prevails among the lower classes, and among the higher alternates with radical unbelief and subversive notions. The houses are adorned with painted images of saints, on whom various forms of adoration are lavished. The churches in the towns, consisting chiefly of frame houses, are striking by their gaudy domes and spires and lofty double crosses, which from a distance attract the eye of the traveller, and relieve the monotony of the vast plains.

The mass of the Great Russians are agriculturists, mechanics, laborers in towns, or itinerant traders; the Little Russians are largely engaged in rearing cattle and horses. Among the non-Slavic nations the following are the most important: 1. The Letts have maintained themselves almost pure in the Baltic provinces, especially in Courland; while, as Lithuanians, in the governments of Wilna, Grodno, and Kovno, they have largely amalgamated with Poles. 2. The Germans are, though not a majority, the predominant race in the Baltic provinces. They also have flourishing settlements throughout southern Russia, and large numbers of German scholars, physicians and druggists, artisans, mechanics, miners, military men, etc, are found in the large cities. 3. The Finns have from the oldest times occupied the northern part of European Russia and a portion of Siberia. To them belong the Finns strictly so called and the Lapps in Finland, the Tchuds, the Vots, the Livs, and the Esths (in Courland, Livonia, Esthonia, Vitebsk, Pskov, St. Petersburg, Archangel, and Olonetz), and a number of tribes on the Volga and in the adjoining territories. (See Finns.) 4. The Tartar race is represented by the Tartars proper in the Crimea, Transcaucasia, Astrakhan, and West Siberia; the Nogais on the Kuban and Don, and in Taurida; the Meshtcheriaks in Orenburg; the Bashkirs in Orenburg, Ufa, and Perm; the Kirghiz between the Ural and Irtish rivers; and Yakuts in Yakutsk and Yeniseisk. 5. The Mongolian race in the wider sense, which embraces the two preceding races, is further represented by the Buriats, Tungu-sians, Ainos, and other tribes in East Siberia; the Calmucks in Astrakhan, the Don Cossack country, Caucasia, and Siberia; the Samoyeds and Ostiaks on both sides of the Obi; and Uz-becks, Turkomans, and Tajiks in the recently annexed territories of central Asia. 6. Among the numerous Caucasian tribes, the Circassians, Lesghians, Georgians or Grusians, and Mingre-lians are the most prominent. 7. The Persians and Armenians are represented in Transcaucasia. The Jews are most numerous in Poland and West Russia. Formerly they were not allowed to live in Great Russia, from which they had been expelled in the 11th century; and even now they are admitted there and in some other parts only under various restrictions, and nowhere in the empire do they enjoy full rights of citizenship.

Greeks are especially found in Odessa and some other large cities. As to social position, the population is divided into three classes with hereditary rights, the nobles, the inhabitants of towns, and the country people. Peter the Great abolished the dignity and official privileges of the boyars (see Boyar), and since then the nobility have lost their prerogatives as a caste, and the offices of the empire are accessible to all. In 1722 he established a regulation of class (tchin), which is still in force, concerning the rank of the officers of state, dividing them into fourteen classes, the first eight of which have hereditary nobility conferred on them, while the members of the other six obtain only a personal nobility. In 1872, according to Lind-heim (Die wirthschaftlichen Verhältnisse des Russischen Reiches, 1873), there were 591,266 noblemen of hereditary and 327,764 of personal rank. The legal relations of the inhabitants of the towns were reorganized by a ukase in June, 1870. The citizens of a town elect a magistrate or town council (duma), which in turn elects a committee (uprava) and the mayor. In smaller towns no committee is elected, but its functions are performed by the mayor.

The aggregate population of the towns amounted in 1872 to 6,907,071. The bulk of the population consists of the peasants, numbering about 56,300,000. Before the act of emancipation, they were divided into three classes, viz., free peasants, peasants under the special administration of the crown, and serfs. The first class included the odnodvortzi or freeholders, who until 1845 formed a subdivision of the country nobility, but were transferred to the class of peasants when, by order of the emperor, the titles of nobles were examined. The second class comprised the crown peasants, holders of land by socage, some 16,000,-000; the domain peasants; the peasants bestowed on nobles and merchants in some manufacturing districts, on condition that they should return to the crown in case the manufactories were closed; and the exiles in Siberia. The serfs numbered about 22,000,000, and belonged partly to the crown and partly to the nobles. Russian serfdom dates from the beginning of the 17th century, when the field laborers were gradually deprived of the right to move at will from master to master. They were attached to the soil, which they could not leave without the consent of the master; the latter, on the other hand, not having the right to dispose of the serfs without the land.

In the spring of 1861 an imperial manifesto, dated Feb. 19 O. S. (March 3), providing for the emancipation of the serfs, was read in all the churches of the empire. - The great majority of the inhabitants belong to the Russian church, which in doctrine entirely agrees with the other branches of the Greek church, while in administration it is distinct. Since the times of Peter the Great it has been governed by a "holy synod," which is one of the supreme boards of the empire. It is dependent on the emperor in questions of administration, but not of dogma or of rites. The bishops composing the holy synod reside partly in St. Petersburg and partly in their dioceses. The church is divided into 52 archi-episcopal dioceses or eparchies. The church in 1870 had 62 archbishops and bishops, 385 monasteries with 5,750 monks, 154 nunneries with 3,226 nuns, 1,334 arch priests, 40,852 priests, 11,852 deacons, and 70,280 clerks, who discharge the duties of readers, chanters, sacristans, beadles, and singers; The total number of churches was 33,100, including 59 cathedrals. The four ecclesiastical academies at St. Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev, and Kazan have of late been reorganized; in 1872 they numbered 106 professors and 410 students, and there were also 51 theological seminaries with 15,585 students.

The lower clergy are mostly poor and ignorant, but the government of the present emperor has made better provisions for their theological education, and established a central relief fund for raising their salaries, the minimum of which was fixed in 1869 at 300 rubles. The church service is performed in the Old Slavic language, which the mass of the people do not understand at all. The liturgy contains, besides the prayers common to all the liturgies of the Greek church, special prayers for every separate member of the imperial family. Sermons were formerly a rare exception at divine service; but recently, owing to the better education of a portion of the clergy, the movement for making the sermon a part of the service is gaining ground. Every member of the Greek church is obliged to take the sacrament once a year. The established church has some special privileges, as the ringing of the larger bells, public processions, etc. None of its members are allowed to secede to another denomination, and all children born of mixed marriages are claimed for it. All foreign princesses marrying into the imperial family must likewise embrace the national religion.

In other respects Catholics and Protestants enjoy equal civil rights with members of the established church, and are equally admissible to the highest offices of the empire; while unconverted Tartars are admitted to military offices. The political separation of the Russian church from the main body of the Greek church took place after the flight of the Greek patriarch from Constanti-. nople to Moscow in the 16th century. Archbishop Isidore of Kiev and Moscow in 1439 visited the council of Florence to promote a union of the eastern churches with the Latin, but on his return was arrested and deposed. Feodor I. in 1589 appointed the first Russian patriarch, and even obtained for the new dignity in 1593 the recognition of the four oriental patriarchs. The patriarchate was again abolished by Peter I., who transferred the supreme administration to the "holy synod," reserving for himself and his successors the headship of the church. To a still higher degree was the church stripped of her independence under Catharine II., the secular government assuming all the property of the church and the education and appointment of the clergy. In point of zeal and activity the Russian church cannot compare with the Roman Catholic and the Protestant churches.

A Bible society was organized under Alexander I.; it was suppressed during the reign of Nicholas, but has resumed its operations under Alexander II. A number of years ago a few members of the highest Russian aristocracy joined the Roman Catholic church; and Prince Gagarin (who entered the order of the Jes-suits) maintained that there was in the Russian church a considerable party favorable to a corporate union of the church with Rome. There is also a small party which endeavors to establish closer relations with the churches of the Anglican communion and with the Old Catholics. The membership of the established church in 1871 was stated at 53,139,000 in Russia proper, 30,000 in Poland, 42,000 in Finland, 1,930,000 in Caucasia, and 2,875,000 in Siberia. In central Asia the population connected with the Greek church was estimated in 1874 at about 130,000. Thus in the whole empire the population belonging to this church is supposed to exceed 58,000,000. There is, however, a vast number of sects, some of which are recognized by the government and their statistics given (although said to be under-estimated) by the minister of public worship.

Of the latter there are the Dukhobortzi, or Champions of the Holy Spirit; the Molokoni, or Milk Drinkers; the Khlysti, or Flagellants; and the Skoptzi, or Eunuchs, also called White Doves, who practise castration. These last have existed from ancient times, and have their adherents chiefly among the wealthy. Besides these, writers mention the Little Christians, Helpers, Non-Payers of Rent, Napoleonists, and others. The largest body, the existence of which the government ignores, is the Ras-kolniks, whose origin is assigned to the popular opposition to certain reforms introduced in the 17th century by the patriarch Nikon, especially to changes in the Slavic translation of the Bible and in the Slavic liturgical books. They call themselves Starovertzi or Old Believers. As their antipathy to change often extends to political measures, they have been generally persecuted by the government. Their history is but little known, and accurate statistics cannot be obtained. Their number has been variously estimated at from 1,000,000 to 17,-000,000; the best authorities incline toward the highest estimate. The United Greek church some years ago numbered about 230,000, all Ruthenians in Poland; in the spring of 1875, however, the bulk of them joined the Orthodox church.

The Gregorian Armenian church has six eparchies: Nakhitchevan, Bessarabia, Astrakhan, Erivan, Gruso-Imerethia, Karabagh, and Shirvan. The most celebrated literary institution of this church is the Lazareff institute for oriental languages at Moscow, which provides for the education of 20 youths. The number of Gregorian Armenians is said to be 37,000 in European Russia, and 561,000 in the Caucasus. The Roman Catholic population is given as 2,883,000 in Russia proper, 4,326,000 in Poland, 830 in Finland, 18,000 in the Caucasus, and 25,000 in Siberia. The Protestant population, a large majority of whom are Lutherans, is 2,234,000 in Russia proper, 331,0(0 in Poland, 1,797,000 in Finland, 10,600 in Caucasia, and 5,700 in Siberia. The number of Mohammedans amounts to 7,225,000: 2,359,-000 in European Russia, 1,960,000 in Caucasia, 61,000 in Siberia, and 2,843,000 in central Asia. The Lutheran church is divided into six consis-torial districts. The general consistory has its seat at St. Petersburg. A Lutheran theological faculty is connected with the university of Dorpat. The Reformed denomination has about 30 churches, mostly in Lithuania, where they are organized into a synod. The scattered Reformed congregations in other parts of the empire are under the direction of Lutheran consistories.

The Mennonites claimed in 1873 a population of nearly 40,000, chiefly in South Russia; but as the new military law abolished the exemption from military duty which had formerly been conceded to them, they resolved to emigrate to the United States. (See Mennonites.) The Moravians have prosperous missions in Livonia and Esthonia, where they have more than 250 chapels and 60,000 members. Recently the Baptists have also established a few missions, which in 1873 resolved upon forming a Russian organization. The Jews number about 2,647,000 (1,829,000 in Russia proper, about 800,000 in Poland, and the remainder in Caucasia and Siberia). The most numerous of the pagans, whose number is estimated at about 550,000, are the Buddhists, with 380 places of worship and 4,400 priests. - The cause of public education was first effectively promoted by Peter the Great, who caused Russia to take the first step toward European civilization. Catharine II. founded many schools and literary institutions. Alexander I. made great efforts in behalf of the people, and tried to establish a complete system of public instruction.

The principal departments of education, with the exception of the military schools, are under the superintendence of the ministry of public instruction, established in 1802. The empire (excepting Finland) is divided for educational purposes into ten circles, each of which is under the superintendence of a curator, viz.: St. Petersburg, Moscow, Dorpat, Kiev, "Warsaw, Kazan, Kharkov, Wilna, Odessa, and the Caucasus. There are eight universities: at St. Petersburg, Moscow, Dorpat, Kiev, Warsaw, Kazan, Kharkov, and Odessa. Finland has a university of its own at Helsingfors. Dorpat is the only one which has a theological faculty. The number of professors at the eight universities in 1873 was 545; of students, 6,697. The number of lyceums and gymnasiums was 126, of pro-gymasiums 32; the aggregate attendance of these institutions was 42,791. According to the report of the minister of public instruction in 1872, the number of popular schools was 19,658, with 761,129 pupils, of whom 625,784 were boys and 135,345 girls. The number of special schools was 206, with 41,-553 pupils. The number of learned societies in connection with the ministry of public instruction in 1873 was 32, of which 9 belonged to universities or similar institutions and 23 had an independent existence.

The imperial academy of science at St. Petersburg, founded in 1723-'5, ranks high among societies of this class. Several scientific establishments belong to other departments of the state; among them are institutions dependent on the ministry of the navy, a law school, polytechnic schools, commercial academies, a considerable number of agricultural and mining schools, and navigation schools. The study of oriental languages has been cultivated of late with special zeal, and no other university of Europe has so many active professors of Asiatic languages as that of Kazan. The number of newspapers in 1868 was 219, of which 117 were published in Russian, 30 in German, and 20 in Finnish. According to official accounts, there were in 1872, in 197 towns, 360 printing establishments, 366 publishers and booksellers, and 261 circulating libraries. There are few public libraries outside of St. Petersburg, Moscow, and Warsaw; but the foundation of such institutions has been laid in many of the provincial towns, and the so-called imperial public library of St. Petersburg contains 1,100,000 volumes in all languages. The position of women in Russia, up to the time of the empress Catharine, was very much degraded. That sovereign did all in her power to raise both their intellectual and social standing.

Among other measures was the establishment of a seminary for girls in St. Petersburg; the girls who entered this were not permitted to leave before seven years, when their education was considered complete. The seminary was divided into two parts, one of which belonged to the nobility and the other to the middle class; the number of girls educated therein was 500. Since that time (1764) institutions for female education have been constantly increasing all over Russia. Female gymnasiums have been established throughout the country, the number of which was given in 1873 as 200, and that of the pupils 23,000. These institutions are all supported by special municipal tax, and have not only contributed to the education of Russian women, but also diminished the antipathies and prejudices arising from inequality of birth, social position, and fortune. The pupils are admitted to the gymnasiums without distinction of parentage, and they wear in many instances a uniform dress. Where the population is mixed, no distinction is made even in the nationality of the pupils, so that the Tartar and the Bashkir girls in the east are brought together with the Russian girls, just as the Polish are in the west.

Taking into consideration the comparatively recent date at which the education of girls in Russia has been cared for, the Russian women have shown remarkable aptitude. Out of 63 female students at the university of Zürich in 1872, 54 were Russians. The question of religion is not regarded in the admission of pupils into the schools; all denominations have an equal right in this respect, and there are priests and parsons attached to the establishments to give religious instruction. Even the Jews and Mohammedans form no exception. Where the number of pupils belonging to a certain sect is not sufficient to warrant the retention of a clerical teacher, the parents are left to provide religious instruction. - The penalties of death and of corporal punishment have been almost entirely abolished in Russia. The former is pronounced now only for high treason, and no criminal court of the land can inflict it; only special high tribunals appointed for exceptional cases having that power. Corporal punishment is maintained only in Siberia as a disciplinary measure among the convicts.

The criminal statistics of 1860-'68 show an average of 534,000 civil, criminal, and police cases in the whole empire; the number of persons sentenced was about 84,000, or less than 17 per cent. of the whole number brought to trial; of these, 1,211 persons were sentenced to hard labor, 2,172 to exile in Siberia, 2,488 to transportation, 6,667 to enrolment in convict companies which are kept in the fortresses for heavy manual labor, 13,669 to imprisonment, and 57,757 to smaller punishments; 31 per cent. of the whole number were cases of theft, and only 2 per cent. were cases of murder and homicide; the number of women included in the 84,000 convicts was 8,800, or a little more than 10 per cent. - The silver ruble is established by an imperial decree of 1839 as the legal and unalterable metallic unit of the money current in the empire. Its value is equal to 37 1/2d. in English, or 73.4 cts. in American money. A ruble is divided into 100 copecks. Gold pieces of 3 and 6 rubles, and a few platinum pieces of the same value, are coined; but the main medium of circulation is paper money, which stands abroad at over 15 per cent. discount. The English inch and foot are generally used throughout Russia, except in measuring timber for the export duties.

The arshin and the sazhen are used as measures of length. The arshin equals 2 1/3 English feet; the sazhen, 7 English feet. For the measurement of distances they have the versta (verst), equal to 3,500 feet, or a little more than three fourths of an English mile. The smallest weight is the zolotnik = 6 grains; 3 zolotniks = 1 loth; 32 loths = 1 pound (the Russian pound is the same for gold, silver, and merchandise); 40 pounds = 1 pood; 1 pood = 36 lbs. 1 oz. 10 drs. avoirdupois. Time continues to be reckoned in Russia by the Julian calendar; yet in business with foreign countries the Russians use both the Julian and Gregorian dates. - The finances of the empire suffered greatly from the European wars which were carried on under Alexander I.; but they were somewhat improved under the able administration of Count Kankrin. During the reign of Nicholas no reports of the condition of the finances were published; and it is only since 1862 that any publication of this kind has taken place. Now, however, the government publishes annually a budget, though both the receipts and expenditures are frequently manipulated so as to produce a more favorable impression than the truth would warrant.

Subjoined is a table showing the general condition of the finances from the beginning of this century:

YEARS. | Revenue, rubles. | Expenditure, rubles. | Surplus ( + ) or deficit (-). |

1800......... | 65,700,000 | 63,100,000 | + 2,600,000 |

1810......... | 64,188,000 | 71,245,000 | 7,057,000 |

1820......... | 128,220,000 | 134,000,000 | - 5,780,000 |

1830......... | 116,245,000 | 118,817,000 | - 2,572,000 |

1640......... | 165,190,000 | 187,979,000 | - 22,789,000 |

1850............................. | 224,640,000 | 287,186,000 | - 62,546,000 |

1860......... | 386,916,000 | 438,239,000 | - 51,323,000 |

1861......... | 411,584,000 | 413,796,000 | - 2,212,000 |

1862......... | 379,373,000 | 389,136,000 | - 9,763,000 |

1863......... | 418,974,000 | 438,998,000 | - 20,024,000 |

1864......... | 393,721,000 | 444,979,000 | - 51,258,000 |

1865......... | 418,897,000 | 432,107,000 | - 13,210,000 |

1866......... | 352,695,000 | 413,298,000 | - 60,603,000 |

1867......... | 419,838,000 | 424,904,000 | - 5,066,000 |

1868......... | 421,560,000 | 441,282,000 | - 19,776,000 |

1869......... | 457,496,000 | 468,797,000 | - 11,301,000 |

It appears from this table that, while both the revenue and expenditures during the period from 1800 to 1869 increased more than sixfold, yet the expenditures regularly exceeded the revenue. Since 1871 both the budgets and the accounts of actual receipts and disbursements, as published by the government, bear a more favorable aspect, as is partially shown by the following table:

BUDGET. | ACTUAL. | |||

YEARS. | Revenue, rubles. | Expenditure, rubles. | Revenue, rubles. | Expenditure, rubles. |

1871..... | 470,692,000 | 510,613,000 | 508,188,000 | 499,735,000 |

1872..... | 497,178,000 | 469,400,000 | 527,621,291 | 523,783,503 |

1873...... | 517,349,000 | 517,322,000 | ................. | ................. |

1874...... | 539,851,000 | 536,683,000 | ................. | ................. |

The only direct tax of the empire is a poll tax (in 1874, 94,631,469 rubles) levied from the peasantry and raised at little expense. Customs (53,068,000) of a protective nature, and the excise duties (206,068,044), mostly laid on spirits, beer, salt, and tobacco, form the bulk of the indirect taxes. The largest branches of expenditure are those for the army. (170,192,553 rubles), the navy (24,847,685 rubles), and the national debt (93,257,877 rubles), the last named branch comprising interest and sinking fund. The public debt in January, 1873, was as follows:

Rubles. | |||

I. | Fund debt........................................................................ | 905,693,564 | |

1. Foreign redeemable debt................. | 157,492,827 | ||

2. Home " " | 270,348,850 | ||

3. Foreign irredeemable debt............... | 275,728,199 | ||

4. Home " " | 202,123,688 | ||

II. | Debts not entered in the great book............................... | 552,618.672 | |

III. | Debts of the Imperial Russian bank............................... | 818,769,328 | |

Total................................ | 2,277,081,564 | ||

From these amounts may be deducted the sum of 412,000,000 rubles which has been advanced to railway companies, to corporations, and to towns, leaving an actual debt of about 1,864,-000,000 rubles. Banking business has of late years received a considerable impulse. There are not fewer than 40 joint-stock banks in Russia, with an aggregate capital of 104,000,000 rubles. Five of these are in St. Petersburg. There are also a number of territorial (zhemski) banks, by means of which the government was enabled to carry through the emancipation of the peasants. The government advanced to landowners from 1861 to 1873 the sum of 628,-439,844 rubles. The entire amount, with interest, is to be redeemed by the peasants, but in the mean time the state assumes the responsibility for its repayment. - The ukase of Nov. 16 (4 O. S.), 1870, announced the adoption by the Russian government of the principle of universal liability to military service, and another of Jan. 13, 1874, reorganized the entire military system. The armed forces of the empire are now to consist of a standing army and of a militia. The standing army embraces the land and naval troops.

The land troops comprise: 1, the active army, which is to be kept up by annual recruitings; 2, a reserve force, formed of men whose term of service in the active army has expired; 3, the Cossacks and other regular troops of various Asiatic tribes. The militia is composed of all men from 20 to 40 years of age, capable of bearing arms, who do not belong to the standing army; a portion of this militia, containing the younger men, can in time of war be employed for filling up the regular forces. Every Russian subject who has attained his 20th year and is not physically incapacitated is liable to service, immunity from which by purchasing a substitute is prohibited; the period of service is fixed at 15 years, six of which are to be spent in an active force, and nine in the reserve; the recruiting is done by drawing lots, and those who do not enter into the regular army have to serve in the militia. The entire empire is divided into recruiting districts. Young men who belong to the so-called liberal professions, and have received a certain degree of education, have the duration of their service in the active army restricted to six months, 18 months, three years, or four years, according to the degree they have attained; there are also volunteer engagements of three months, six months, and two years, as in France, equally in accordance with the educational privileges of the young men.

But a nine years' reserve service is obligatory upon all such men.. The infantry and the cavalry of the army, now (1875) in course of reorganization, are to have for their military unit the division, composed of four regiments; the artillery, riflemen, and engineers are to be formed into brigades. Twelve regiments d'élite and a brigade of riflemen will still form the corps of imperial guards stationed at St. Petersburg, while the remaining 45 divisions of infantry are to be formed into 15 corps, each consisting of three divisions of infantry, one of cavalry, and a number of Cossacks, artillery, and engineers. Each division of infantry consists of two brigades, each brigade of two regiments of three battalions each, each battalion of four companies, and each company of 250 men. Each division of cavalry is to consist of two brigades, each brigade of three regiments, and each regiment of four squadrons of 250 horses. The cavalry brigade consists of a regiment of dragoons, a regiment of lancers, and a regiment of hussars. A brigade of artillery consists of six batteries of eight guns each. Of these batteries, three are of nine-inch guns, two of four-inch guns, and one of mitrailleuses.

The whole regular army will thus consist of 192 regiments of infantry, 56 regiments of cavalry, and 2,256 guns, besides seven brigades of riflemen (one of the guards). The engineer corps is composed of six brigades of sappers and six half battalions of pontoniers. The Cossacks are divided into regiments of 10 sotnias of 100 men each; they now comprise 153 mounted regiments, with 37 battalions on foot, and 28 batteries. The number of these troops can be increased ad libitum at any time, as all the Cossacks are liable to life-long service. The army is now (1875) estimated at 750,000; but the whole military force of Russia in case of war can be brought to 1,500,000, with 300,-000 horses, half of which is designed to be used for offensive operations, and the other half for defensive only. The Russian navy is commanded by 81 admirals and 2,990 officers of all ranks, and contains 25,500 sailors and marines. The fleet consists of 225 steam vessels, with 521 guns, of a total tonnage of 172,-501 and total horse power of 31,978, distributed as follows: Baltic fleet, 27 ironclads with 200 guns, 40 steamships with 170 guns, and 70 transports; Black sea fleet, 2 ironclads with 8 guns, 25 steamships with 45 guns, and 4 transports; Caspian fleet, 11 steamships with 45 guns, and 9 transports.

There are also 37 steamers with 53 guns, of a tonnage of 2,424 and a horse power of 2,250, scattered in the sea of Aral and on the Pacific and Arctic coasts. The administration of the navy is in the hands of the minister of marine, assisted by an admiralty council, but the supreme command of the fleet is vested in the grand admiral, now the grand duke Constantine, brother of the czar. The great naval stations are Cronstadt in the gulf of Finland and Sebas-topol on the Black sea. The great navy yards are those of St. Petersburg at the mouth of the Neva, and Nikolayev in the Black sea. - The ancient history of Russia is involved in great obscurity. (For an account of theories concerning the name Rus in its earliest connections, see Japheth.) The Greek and Roman writers mention the Scythians and the Sarmatians as the inhabitants of the vast and unknown, regions of the north, especially of the country between the Don and the Dnieper, a description of which is given by Herodotus. Strabo and Tacitus say that the Roxo-lani, a Scythian tribe, which according to the testimony of the later writer Spartianus was ruled by kings, lived on the Don. The Greeks entered into commercial relations with them, and established some colonies in their territory.

During the migration of nations in the 4th and the following centuries, Russia witnessed the movements of hordes of Goths, Alans, Huns, Avars, Bulgarians, and others. Soon after the name of the Slavs appears for the first time, a race, according to the general opinion of historians, identical with the Sarmatians, and believed to have extended northward as far as the upper Volga. The Slavs found scattered Finnish tribes dwelling in these territories, and drove them higher north toward Finland and the region of the Arctic sea. Such of these people as did not remove became amalgamated with the invaders, and gave their descendants that indifferent color of hair and sallow complexion which most Russians of our day possess. Thus the people now known as Russians are a compound product of the various Slavic tribes, of many Scythic tribes, especially the Tartars, who in the middle ages oppressed Russia for centuries, and of Finns. (See Slavic Race and Languages.) The Slavs founded the towns of Novgorod and Kiev, both of which became the capitals of independent Slavic principalities.

After a history of about 100 years, of which nothing is known, the principality of Novgorod, of unknown extent, and surrounded by a number of tribes of Finns of the Tchudic branch, appears struggling against the invasion of the Varangians (called by the Slavs Rus), a tribe of Northmen, who succeeded in making both the Slavs and Finns tributary. For a time the Slavs threw off the yoke of the Varangians, but sinking into anarchy and feeling themselves unable to cope with internal and external foes, they, together with some of the neighboring Finnish tribes, invited Rurik, the prince of the Varangians, to Novgorod, where he arrived about 862, with his brothers Sineus (or Sinaf) and Truvor, and laid the foundation of the great Russian empire. For nearly 200 years Russia remained under the autocratic power of the descendants of Rurik. He died in 879, leaving the empire, not to his son Igor, who was only four years old, but to his cousin Oleg, a great conqueror and wise ruler. Oleg (879-912) conquered the principality of Kiev and united it with his own, vanquished the Khazars (probably a people of Turanian origin, who in the 7th and 8th centuries had established a powerful kingdom between the Dnieper and the Caspian, being ruled for a time by a dynasty converted from Islam to Judaism), drove the Magyars out of the borders of Russia toward the country now occupied by them, and made an expedition by land and sea (with 900 vessels) against the emperor of Constantinople, with whom in 911 he concluded an advantageous peace.

Igor, the son of Rurik (912-'45), put down an insurrection of the Drevlians on the Pripet, conquered the Petchenegs, who lived on the coasts of the Black sea from the Danube to the mouths of the Dnieper, made an unsuccessful war against the emperor of Constantinople in 941, and was slain in a second war against the Drevlians. During the minority of his son Sviatoslav (945-'72), his widow, the celebrated Olga, held the reins of government with wisdom and energy. In her reign Christianity began to spread in Kiev, and Olga herself was baptized in 957 at Constantinople. Her son Sviatoslav, who remained a pagan, won new victories over the Khazars, subdued the Bulgarians and Petchenegs, and was slain by the latter, while returning through their territory from a war against Constantinople. He had extended the borders of the empire to the sea of Azov, and in 970 divided it among his three sons, giving Kiev to Yaropolk I. (972-'80), the country of the Drevlians to Oleg, and Novgorod to Vladimir. In a war which arose between the three brothers, Oleg was slain and Vladimir fled, and the whole empire was reunited under Yaropolk; but in 980 Vladimir returned with Varangian hordes, conquered Novgorod and Kiev, and, having put his brother to death, became the ruler of all Russia. Vladimir, surnamed the Great on account of the benefits he conferred on the empire, conquered Red Russia and Lithuania, and made Livonia tributary.

He at first opposed Christianity, but subsequently declared himself ready to embrace the doctrines of the Greek church, married the sister of the emperor of Constantinople, and was baptized in 988 on the day of his wedding. He soon after ordered the introduction of Christianity into the entire empire, established churches and schools, and founded new towns. He divided the empire among his twelve sons, who, even before the death of the father in 1015, engaged in a fratricidal war, in which at length Sviatopolk, a son of Vladimir's brother Yaropolk I., but adopted by Vladimir, possessed himself of the throne, after murdering three of his brothers. Another brother, Ya-roslav, allied himself with the emperor Henry II. of Germany against Sviatopolk, and the father-in-law of the latter, King Boleslas of Poland. The war lasted till 1019, when a three days' battle decided in favor of Yaroslav, and Sviatopolk died on his flight in Poland. Yaroslav (1019-54) for some time was sole ruler; but in a war against his brother Msti-slav, prince of Tmutorakan on the strait of Yenikale (who in 1016 had destroyed the Crimean remnant of the kingdom of the Khazars, and in 1022 subdued the Circassians), he was routed in 1024, and purchased peace by ceding to his brother one half of the empire.

After the death of Mstislav in 1036, the entire empire became once more united under Yaroslav. By several successful wars he considerably enlarged its territory, and like his father introduced many useful reforms. He caused the translation of many Greek works into Slavic, built churches and schools, increased the number of towns, peopled many waste tracts of land, and ordered the compilation of the Rus-skaya Pravda, the first Russian code. Three of his daughters were married to the kings of Norway, France, and Hungary. A few days before his death he divided the empire among his four sons, with the provision that the three younger ones should obey the eldest brother Izaslav, to whom he gave Kiev and Novgorod. But this provision proved of little avail; the four divisions of the empire were again subdivided, and the Russian monarchy was finally changed into a confederacy. The power of the nation was broken by a never ceasing internal war, and large territories in western Russia were taken possession of by the Poles, Lithuanians, Danes, Teutonic knights, and others.