China. Part 21

Description

This section is from the book "China - John L. Stoddard's Lectures", by John L. Stoddard. Also available from Amazon: John L. Stoddard's Lectures 13 Volume Set.

China. Part 21

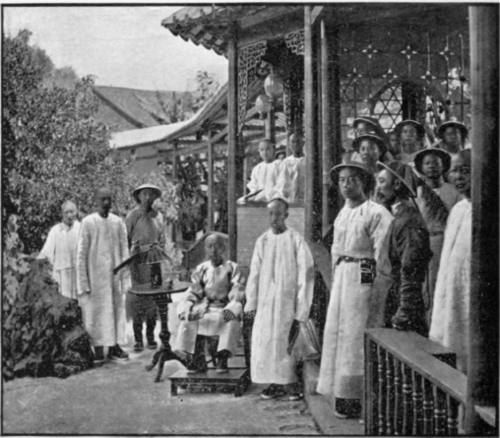

A Chinese General And His Attendants.

Those who succeed in standing the third, or "Imperial," test at Pekin - severer even than the other two, - have reached the apex of the pyramid. They are now mandarins, and have acquired all they can desire, - social distinction, office, wealth, and (what is sometimes still more highly prized) great national fame. For in the results of this examination the entire country takes the greatest interest. The names of the successful men are everywhere proclaimed by means of couriers, river-boats, and carrier- pigeons, since thousands of people in the empire have laid their wagers on the candidates, as we might do on horses at the Derby. Strange, is it not, to think that this elaborate Chinese system was practised in the land of the Mongols substantially as it is to-day, at a time when England was inhabited by painted savages?

Moreover, the honors of successful candidates in China cannot be inherited. Young men, if they would be ennobled, must surpass their competitors and win their places as their fathers did. Even the youthful son of Li Hung Chang, whom General Grant considered, next to Bismarck, the most remarkable man he met with in his tour around the world, is not entitled, because of his father's office, to any special rank. Hence, China, though an absolute monarchy, has no privileged class whose claims rest merely on the accident of birth. Her aristocracy consists of those who have repeatedly proved themselves intellectually superior to their rivals. Among no people in the world, therefore, have literary men received such honors as in China; and it is a remarkable fact that this vast nation has worshiped for two thousand years, not a great warrior, nor even a prophet claiming inspiration from God, but a philosopher, - Confucius.

Li Hung Chang.

Li Hung Chang And Suite On Their Tour Around The World.

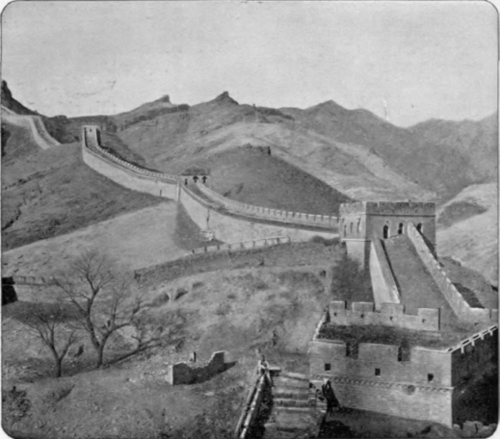

I have often thought that were I asked to compare the Chinese empire of to-day with some material object, I would select for such comparison the Great Wall on its northern frontier. This mighty work has hardly been surpassed in the whole history of architecture, not even by the builders of the Pyramids. It is no less than twenty-five feet high and forty feet broad, with watch-towers higher still, at intervals of three hundred feet. And yet it has a length of nearly fifteen hundred miles, a distance exceeding that from Boston to St. Paul, and in its uninterrupted march spans deep ravines and climbs to lofty mountain crests, in one place nearly five thousand feet in height. Although it was built three hundred years before the birth of Christ, it still exists, and during fourteen centuries sufficed to hold in check the savage tribes of Tartars from the north. It has been calculated that if the Great Wall were constructed at the present time, and with Caucasian labor, its cost would pay for all the railroads in the United States. One hundred years ago an English engineer reckoned that its masonry represented more than all the dwellings of England and Scotland put together, and, finally, that its material would construct a stone wall six feet high and two feet thick around the entire globe.

The Great Wall Of China.

In many respects this great rampart is typical of China. Both have a vast antiquity, both have an enormous extent, and both have had their periods of glory, - China her age of progress and invention, and this old wall a time when it was kept in perfect order, when warriors stood at every tower, and when it stretched for fifteen hundred miles - an insurmountable barrier to invasion. But just as this leviathan of masonry has outlived its usefulness, and is at present crumbling to decay, so the huge Chinese empire itself now seems decrepit and wholly alien to the nineteenth century. Her roads, once finely kept, are now disgraceful; her streets are an abomination to the senses; her rivers and canals are left to choke themselves through want of dredging; and even her temples show few signs of care. Stagnation and neglect are steadily at work on her colossal frame, as weeds and plants disintegrate this mouldering wall. Will this old empire ever be aroused to new activity, and can fresh life-blood be infused into her shrunken veins to animate her inert frame? There is, I think, a possibility that, in the coming century, the new, progressive party here will overcome the dull conservatism of the nation, connect her vast interior with the sea, utilize her mineral wealth, develop her immense resources, and make her one of the great powers of the world. Napoleon once warned England that if the Chinese should learn too well from her the art of war, and then acquire the thirst for conquest which has characterized other nations, the result might be appalling to the whole of Europe. For think what inexhaustible armies they could raise, and what great fleets they could build and launch upon their mighty rivers! But this is a problem of the future, about which no man can predict with certainty.

Continue to: