Our Enemies, The Microbes

Description

This section is from "Scientific American Supplement". Also available from Amazon: Scientific American Reference Book.

Our Enemies, The Microbes

We have seen the microbes, as our servants[1], often performing, unbeknown to us, the work of purifying and regenerating the soil and atmosphere. Let us now examine our enemies, for they are numerous. Everywhere frequent--in the air, in the earth, in the water--they only await an occasion to introduce themselves into our body in order to engage in a contest for existence with the cells that make up our tissues; and, often victorious, they cause death with fearful rapidity. When we have named charbon, septicaemia, diphtheria, typhoid fever, pork measles, etc., we shall have indicated the serious affections that microbes are capable of engendering in the animal organism.

[Footnote 1: SUPPLEMENT, No. 446, page 7125.]

We call those diseases "parasitic" that are occasioned by the introduction of a living organism into the bodies of animals. Although a knowledge of such diseases is easy where it concerns parasites such as acari and worms, it becomes very difficult when it is a question of diseases that are caused by the Bacteriaceae. In fact, the germs of these plants exist in the air in large quantities, as is shown by the analysis of pure air by a sunbeam, and we are obliged to take minute precautions to prevent then from invading organic substances. If, then, during an autopsy of an individual or animal, a microscopic examination reveals the presence of microbes, we cannot affirm that the latter were the cause of the affection that it is desired to study, since they might have introduced themselves during the manipulation, and by reason of their rapid vegetation have invaded the tissues of the dead animal in a very short time. The presumption exists, nevertheless, that when the same form of bacteria is present in the same tissue with the same affection, it is connected with the disease. This was what Davaine was the first to show with regard to Bacillus anthracis, which causes charbon.

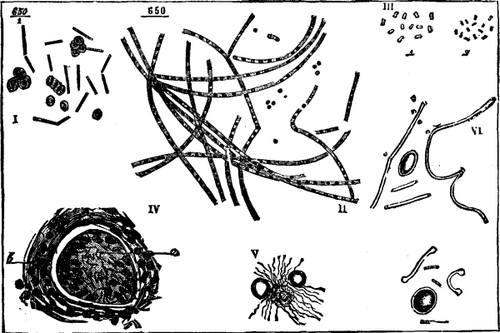

He, in 1850, having examined the blood of an animal that had died of this disease, found therein amid the globules (Fig. 1), small, immovable, very narrow rods of a length double that of the blood corpuscles. It was not till 1863 that he suspected the active role of these organisms in the charbon malady, and endeavored to demonstrate it by experiments in inoculation. Is the presence of these little rods in the blood of an animal that has died of charbon sufficient of itself to demonstrate the parasitic nature of the affection? No; in order that the demonstration shall be complete, the bacteria must be isolated, cultivated in a state of purity in proper liquids, and then be used to inoculate animals with. If the latter die with all the symptoms of charbon, the demonstration will be complete. Davaine did, indeed, perform some experiments in inoculation that were successful, but his results were contradicted by the experiments of Messrs. Jaillard and Leplat, and those of Mr. Bert concerning the toxic influence of oxygen at high tension upon microbes.

As Davaine was unable to explain the contradiction between his results and those of Messrs. Jaillard, Leplat, and Bert, minds were not as yet convinced, notwithstanding the support that his ideas received from Mr. Koch's researches.

In 1877 Mr. Pasteur took up Davaine's experiments, and confirmed his affirmations step by step by employing the method of culture that he had used with such success in his studies upon fermentation. He isolated Davaine's bacterium by cultivating it in a decoction of beer yeast that had been previously sterilized (Fig. 2); and after from ten to twenty cultures, he found that a portion of the liquid containing a few bacteria, when used for inoculating a rabbit, quickly caused the latter to die of charbon, while the same liquid, when filtered through plaster or porcelain, became harmless.

Davaine's bacterium develops exclusively in the blood, and is never found at any depth in the tissues. This is due to the fact that the alga, having need of oxygen in order to live, borrows its flow from the blood, and thus extracts from the globules that which they should have carried to the tissue. The animal therefore dies asphyxiated. It is on account of the absence of oxygen in the blood that the latter assumes the blackish-brown color that characterizes the malady, and that has given its name of charbon (coal).

The parasitic nature of charbon was therefore absolutely demonstrated, first, by the constant presence of Bacillus anthracis in the blood of anthracoid animals, and second, by the pure culture of the parasite and the inoculation of animals with charbon by means of it.

Davaine began the demonstration in 1863, and Pasteur finished it in 1877. These facts are now incontestable; yet, to show how slowly truth is propagated, even in these days of telegraphs and telephones, there might have been read a few months ago, in an interesting article on microbes, by Dr. Fol, a distinguished savant, the statement that charbon and tuberculosis were discovered by Dr. Koch!

New parasitic affections, whose existence was suspected, were soon discovered and scientifically demonstrated, such, for example, as septicaemia, or the putrefaction which occurs in living animals, which in ambulances causes so fearful havoc among the wounded, and which proceeds from Bacillus septicus. This parasite exhibits itself under the form of little articulated rods that live isolated from oxygen in the mass of the tissues, and disorganize the latter in disengaging a large quantity of putrid gas. Other parasites of this class are the micrococcus of chicken cholera (Fig. 3), the micrococcus of hog measles, and the Spirochoete Obermeieri of recurrent fever, discovered by Obermeier (Fig. 5).

Besides these, there are a certain number of maladies that seem as if they must be due to the Bacteriaceae, although a demonstration of the fact by the method of cultures and inoculation has not as yet been attempted. Among such, we may cite typhoid fever, diphtheria, murrain, tuberculosis (Fig. 4), malarial fever (Fig. 6), etc.

As may be seen, the list is already a long one, and it tends every day to still further increase. All the progress that has been made in so few years in our knowledge of contagious or epidemic diseases is due exclusively to M. Pasteur and the scientific method that he introduced through his remarkable labors on fermentation. Now that we know our most formidable enemies, how shall we defend ourselves against them?

As we have seen, bacteria exist everywhere, mixed with the dust that interferes with the transparency of the air and covers all objects; and they are likewise found in water.

Under normal conditions, our body is closed to these organisms through the epidermis and epithelium, and, as has been shown by Mr. Pasteur, no bacteria are found in the blood and tissues of living animals. But let a rupture or wound occur, and bacteria will enter the body, and, when once the enemy is in place, it will be too late. One sole chance of safety remains to us, and that is that in the warfare that it is raging against our tissues the enemy may succumb. M. Pasteur has shown that the blood corpsucles sometimes engage in the contest against bacterides and come off victorious. In fact, chickens are proof against poisoning by charbon, because, owing to the high temperature of their blood, the bacterides are unable to extract oxygen from the corpuscles thereof. But, if the chickens be chilled, the conditions are changed, and they will die of charbon just as do cattle and sheep; but, as the result of the contest cannot always be foreseen, it is necessary at any cost to prevent bacterides from entering the body.

I. Bacteria of charbon (Bacillus antracis.) II. The

same cultivated in yeast. III. The Micrococcus of chicken cholera.

IV. The Bacillus of tuberculosis. V. The Spirillun of

recurrent fever. VI. The Bacillus of malaria.

Under ordinary circumstances a severe hygiene will suffice to preserve us; if a wound is received it should be washed with water mixed with antiseptics, such as phenic acid, borax, or salicylic acid. If water is impure, it must be boiled and then aerated before it is drunk. If the air is the vehicle of the germs of the disease, it will have to be filtered by means of a muslin curtain kept wet with a hygroscopic solution, glycerine for example. Finally, when, after an epidemic, contaminated apartments are to be occupied, the walls and floor and the clothing must be washed with antiseptic solutions whose nature will vary according to circumstances--steam charged with phenic acid, water mixed with a millionth part of sulphuric acid, boric acid, ozone, chlorine, etc.

These preventives only prove efficient on condition that they be used persistently. Let our vigilance be lacking for an instant, and the enemy will enter to work destruction, for it only requires a spore less than a hundredth of a millimeter in diameter to produce the most serious affections.

Fortunately, and it is again to Mr. Pasteur that we owe these wonderful discoveries, the parasitic microbes themselves, which sow sickness and death, may, through proper culture, become true vaccine viri that are capable of preserving the organism against any future attack of the disease that they were capable of producing; such vaccine matters have been discovered for charbon, chicken cholera, the measles of swine, etc.

When the micrococcus of chicken cholera (Fig. 3.) is cultivated, it is seen that the activity of the microbe in cultures exposed to the air gradually diminishes. While a drop of the liquid would, in twenty-four hours, have killed all the chickens that were inoculated with it, its effect after two, three, or four days considerably diminishes, and an inoculation with it produces nothing more than a slight indisposition in the animal, and one that is never followed by a serious accident. It is then said that the virulence of the microbe is attenuated.

The air is the agent of this transformation that gradually renders the bacteria benign, for in cultures made under the same circumstances as the preceding, but with the absence of air, the activity of these algae is preserved for days or weeks, and they will then cause death just as surely as they would have done at the end of one day.

What is remarkable is that animals inoculated with the attenuated micrococcus become for a varying length of time refractory to the action of the most formidable parasites of this kind. Mr. Pasteur has discovered two such vaccine viri--one for chicken cholera and the other for charbon. His results have not been accepted without a struggle, and it required nothing less than public experiment in vaccination, both in France and abroad, to convince the incredulous. There are still people at the present time who assert that Mr. Pasteur's process of vaccination has not a great practical range! And yet, here we have the results; more than 400,000 animals have been vaccinated since 1881, and it has been found that the mortality is ten times less in these than in those that have not been vaccinated!

An impetus has now been given, and we can look to the future with confidence, for, if our enemies are numerous, the use of a severe hygiene and preventive vaccination will permit us to gradually free humanity from the terrible scourges that sap the sources of fortune and life.--Science et Nature.

Continue to: