Chapter 9. The Federal Reserve Act

Description

This section is from the "Economics In Two Volumes: Volume II. Modern Economic Problems" book, by Frank A. Fetter. Also available from Amazon: Economic

Chapter 9. The Federal Reserve Act

§ 1. General banking organization. § 2. The Federal Reserve Board. § 3. Federal Reserve banks. § 4. Federal Reserve notes. § 5. Reserves against Federal Reserve notes. § G. Reserves against Federal Reserve bank deposits. § 7. Reserves in member banks. § 8. Rediscount by Federal Reserve banks. § 9. Changes in national banks. § 10. Operation in the pre-war period. § 11. Operation in the war period. § 12. Gold hoards and artificial interest rates. § 13. The post-war period. § 14. Future of the Federal Reserve system.

§ 1. General banking organization. President Wilson and the newly elected Congress with its Democratic majority made banking reform one of the main objects on the program for the special session beginning March 5, 1913. The result was the Glass-Owen bill, which became law as the Federal Reserve Act December 23 of that year. The bill was actively discussed within and without the halls of Congress, and many of its features were attacked by bankers, individually and acting through the bankers' associations, at various stages of its progress. As a result it underwent numerous amendments in details, and, though it remained in most essentials as it was first proposed, it was at last accepted even by its critics as on the whole a beneficent act of legislation. Indeed, its strongest critics were the friends of the Aldrich plan, and the Federal Reserve Act embodies, in a greater degree than its authors were ready to admit, the main features of the Aldrich plan. In one important respect, however, it is different: it provides for more decentralization of control and of reserves than did the Aldrich plan. It created, not one central banking reserve, but, in the end, twelve regional, or district, banks, each to keep the reserves of its district. The Jacksonian tradition of opposition to a central bank1 in part helps to explain this; in part the contemporary congressional investigation and discussion of the so-called "money-trust" and the consequent desire to decrease the importance of "Wall Street" and of New York City banking power.

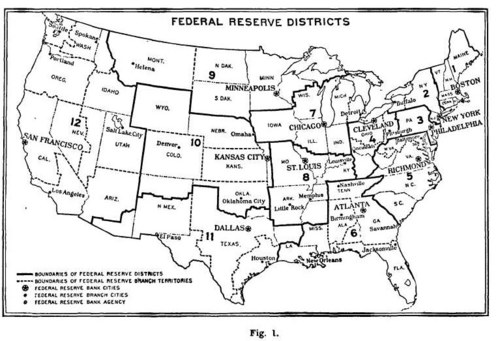

On the accompanying map (Fig. 1) are given the outlines of the districts as constituted and altered down to 1921.2

§ 2. The Federal Reserve Board. At the head of the banking system stands the Federal Reserve Board of seven members, five of them appointed by the President and Senate of the United States for this purpose, and two serving ex-officio—the Secretary of the Treasury and the Comptroller of the Currency. One of the five shall be designated by the President as Governor and one as Vice-Governor of the Board. But the secretary of the Treasury is ex-officio chairman. The term of the appointive members was fixed at ten years and the salary at $12,000 a year.

The powers of the Board are numerous and important. The Board is made the head of a real system of banking, the twelve parts of which can, in times of emergency, and at the Board's discretion, be compelled to combine their reserves by means of lending to each other (rediscounting), to the very limit of their resources, at rates fixed by the Board. By this means the reserves of the several district banks may be "piped together" and thus be practically made into one central bank under the Board's control, although centralization was in outward form avoided by the bill. Alongside of the Reserve Board is placed a Federal Advisory Council, consisting of twelve members, one from each of the boards of directors of the twelve district banks. This council has only the power to confer with, make representations and recommendations to, and call for information from the Federal Reserve Board.

1 See ch. 8, § 1.

2 The law provided that an organization committee should designate not less than eight nor more than twelve cities as Federal Reserve cities, and should divide the continental United States, excluding Alaska, into districts each containing one such city. Twelve districts were designed. Whenever, therefore, the act speaks of "not less than eight nor more than twelve," or of "as many as there are Federal Reserve districts," we may now say twelve. See map, Figure 1, ch. 9.

§ 3. Federal Reserve banks. The twelve Federal Reserve banks, which opened for business November 16, 1914, are institutions of a type new in our financial history. They are "banks for banks," that is, for the "member banks" in their respective districts. Every national bank must, and any state bank or trust company may (on agreeing to comply with reserve and capital requirements for national banks and to submit to federal examination), subscribe for stock to the amount of 6 per cent of its capital and surplus, and thus become a "member bank." The capital of each Federal Reserve bank was to be at least $4,000,000; in fact, only two of those organized (Atlanta and Minneapolis) had at their opening less than $5,000,000 capital; the largest (New York) had $21,000,000; and the average was $9,000,000. The member banks receive dividends of 6 per cent, cumulative, on their paid-in shares of capital, and (beginning 1921, by amendment) all remaining net earnings are added to surplus until it amounts to 100 per cent of the subscribed capital; after that 10 per cent shall be added to surplus and the rest goes to the government as a franchise tax. By the end of 1920 the total surplus of the system exceeded the subscribed capital, and only two of the banks (Cleveland and Dallas) had less than 100 per cent surplus.

Each reserve bank has nine directors, consisting of three classes of three men each. Classes A and B are elected by the member banks by a system of group and preferential voting designed to prevent the large banks from outvoting the smaller ones. Directors of class A are chosen by the banks to represent them, and are expected to be bankers; those of class B, though chosen by the banks and though they may be stockholders, shall not be officers of any bank, and shall at the time of their election be actively engaged within the district in commerce, agriculture, or some other industrial pursuit. Directors in class C are appointed by the Federal Reserve Board, one of them being designated as chairman of the board of directors and as Federal Reserve agent. They represent the public particularly, and may not be stockholders of any bank. Any Federal Reserve bank may:

a. Receive deposits from member banks and from the United States.

b. Discount upon the endorsement of any of its member banks negotiable papers, with maturity not more than ninety days, that have arisen out of actual business transactions, but not drawn for the purpose of trading in stock and other investment securities.

c. Purchase in the open market anywhere various kinds of negotiable paper.

d. Deal anywhere in gold coin and bullion.

e. Buy and sell anywhere bills, notes, revenue bonds, and warrants of the states and subdivisions in the continental United States.

f. Fix the rate of discount it shall charge on each class of paper (subject to review by the Federal Reserve Board).

g. Establish accounts with other Federal Reserve banks and with banks in foreign countries or establish foreign branches.

h. Apply to the Federal Reserve Board for Federal Reserve notes to be issued in the manner below indicated.

Continue to: