Notes

Description

This section is from the book "Myths And Folk-Tales Of The Russians, Western Slavs, And Magyars", by Jeremiah Curtin. Also available from Amazon: Myths and Folk-Tales of the Russians, Western Slavs, and the Magyars.

Notes

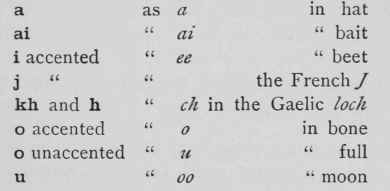

Letters in the Russian names and titles in this volume have the following values: -

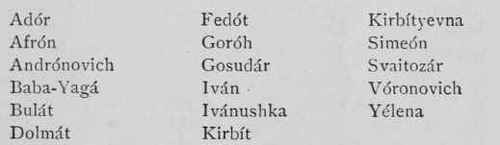

In this volume Russian names and titles without printed accents are accented on the penult. Names and titles accented on syllables other than the penult have the accents indicated in the following list: -

The few titles in the Russian tales are: -

Tsarevich, Tsar's son.

Tsarevna, " daughter.

Tsaritsa " wife.

Korolyevna, King's daughter, princess.

In Chekh and Magyar the accent is always on the first syllable.

In the Magyar consonantal combinations cs = ch, gy = dy, s = sh. Examples are Csako, pronounced Chako, - one of the cows sold by the poor man to the King of the Crows. This is a name given in Hungary to a cow with horns grown outward. Kiss Miklos, pronounced Kish Miklosh, means in English Nicholas Little. Magyar is pronounced Modyor, the unaccented a in Magyar being the equivalent, or nearly so, of our o.

The Russian myth-tales in this volume are all taken from Afanasyeff's1 collection. At the end of each title are given, in parentheses, the part and page of the tale in the original work.

The Three Kingdoms, - The Copper, the Silver, and the Golden. Page 1. (Part vii. p. 97).

The first name, that of the Tsar Bail Bailyanyin, is best translated as "White of White Land." There is in Russian mythology a lady of unspeakable beauty, Nastasya or Anastasya of the sea, who causes the sun to blush twice each day; she is perhaps the Nastasya, Golden Tress, of this story. Bail Bailyanyin, "White of White Land," may well be Bail Bog, the White God of pre-Christian Russians. And here a few words touching the persistence of myth-conceptions may not be out of place. In the tales of the Indians, and in fact of all men who have retained firm traces of primitive thought, the people of the myth-tellers are on the side of light and goodness, and their enemies on that of darkness and harm. This is parallel with the antithesis of day and night. The Russian phrases baili dyen, baili svait, "white day," "white world," are good examples of the old-time idea with which is connected, in all likelihood, the title Baili Tsar, "the White Tsar," still existent in Russia.

1 The Russian title of Afanasyeff's work is, "Narodniya Russkiya Skazki. A. N. Afanasieva, Moskva." There are eight parts, usually bound in three volumes, and dated 1860-61-63.

Ivan Tsarevich, The Fire-Bird, and the Gray Wolf. Page 20. (Part vii. p 121).

The variants of this tale among the Russians and other Slavs, as well as in Germany, are many, and would fill a volume of good size if collected and published. In some Russian variants Ivan Tsarevich retains Yelena the Beautiful, not through the art and friendship of the Wolf, but by his own craft and daring. When he has received the golden-maned steed in exchange for Yelena, and is going, he asks to take leave of the maiden; the request is granted. He raises the beauty to the saddle-bow, puts spurs to the steed, rises in the air, shoots on above the standing forest, below the moving cloud, vanishes, holds on his way till he comes to the Tsar to whom he had promised to give the steed for the Fire-Bird. When the time comes for parting he asks to take a last ride on the steed, if only through the courtyard; the Tsar agrees. Ivan mounts with the cage in his hand; the steed rises as before, and he vanishes, comes to the place where he had left Yelena, and fares homeward with her till he meets his evil brothers.

Ivan the Peasant's Son and the Little Man Himself One - finger Tall, his Mustache Seven Versts in Length. Page 37. (Part viii. p. 109).

[Written down in the government of Saratoff, by Guskoff.]

In this tale we have Freezer and Great Eater, with powers exhibited on a smaller scale than those of the comrades of Kiss Miklos in the Magyar myth. The picture of the boat serving for the reality has its parallel quite frequently in Indian belief.

The Feather of Bright Finist the Falcon. Page 47. (Part viii. p. 1).

Written down in the government of Vologda.

The Pig with Gold Bristles, the Deer with Golden Horns, and the Golden-Maned Steed with Golden Tail. Page 59. (Part ii. p. 268).

Written down in the government of Voronej.

Water of Youth, Water of Life, and Water of Death.

Page 72. (Part vii. p. 66).

The sleeping maiden in this tale, with her slumbering host, reminds us at once of the Queen of Tubber Tintye in "The King of Erin and the Queen of Lonesome Island." See "Myths and Folk-lore of Ireland".

The Footless and Blind Champions. Page 82. (Part v. p. 164).

This tale has many variants in Russian, and resembles the Briinhilde and Gunter story in the "Niebelungen Lied".

The Three Kingdoms. Page 97. (Part viii. p. 91).

This story is remarkable for the change or metamorphosis of Raven, the great power, into a common raven after his defeat by Ivan Tsarevich and the surrender of the feather staff.

Raven is a great personage in American mythology, especially in that of the Modocs. Whenever he appeared and uttered his spell with an ominous laugh, everything was turned to stone. There are many rock groups of Eastern Oregon described in the myths as ancient mighty personages turned into stone by Raven. As soon as the body became stone, however, the spirit escaped, and took physical form in some other place. Over the spirit, Raven had no power.

Koshchei Without-Death. Page 106. (Part vii. p. 72).

[Written down in the government of Archangel.]

This name has been translated, but incorrectly, Koshche'i, the "Deathless" or "Immortal." Koshchei was not deathless.

His death was in the world, but in a place apart from him, which is simply another way of saying that the source of his life was at a distance. We may find in this fact one very important clew to the discovery of the nature of personages like Koshche'i. No matter how they are cut up or slaughtered, where they act, they are alive and as strong as ever next instant; it is as vain to try to kill them by attacking their bodies as it is to destroy winter by making bonfires in the open country, or destroy the summer by artificial cooling. There are two ways by which we may draw conclusions as to who these personages are, - one by discovering what or where their life or death is, the other by examining their acts. We do not know much at present about Koshchei, from the fact that his death is in a duck's egg; but if we could learn who the women are whom he carries away, that would throw light on his character. Let us take an American example. There is a personage, Winter, in a certain Indian myth whose heart is hidden away at a distance, and whose song brings frost and snow. The heart is found by the enemy of the Snow-maker; this enemy burns it, and the Snow-maker dies. In another Indian myth the hero's enemy is pounded to pieces, but comes to life, is killed repeatedly without result. At last the hero learns that his enemy's heart is in the sky, at the western side of the sun at midday; straightway he reaches up, gets the heart, crushes it, and his enemy dies. In this case the enemy is surely not a snow-maker.

Continue to: