Grasses. Part 4

Description

This section is from the book "Field, Forest, And Wayside Flowers", by Maud Going (E. M. Hardinge). Also available from Amazon: Field, Forest, and Wayside Flowers.

Grasses. Part 4

The whole affair is known to botany as a "caryopsis," and to the general public as a grain (Fig. 42). The innermost integument clings tightly to the seed, and each succeeding one adheres to the one beneath it. They peel off with difficulty, still clinging together, so that the grain appears to have a single tough skin.

Fig. 41. - Single flower of a grass, showing two vestigial petals,three stamens, and ovary with two plume-likestyles.

Just inside the innermost skin of the wheat-grain there is a layer of nitrogenous substance, far richer in nutriment than the starchy substances which lie beneath it. When the integuments of the wheat-grain are torn off, this nutritive "aleurone" layer is apt to come away with them. But any process of milling which can keep the aleurone with the starchy inner part of the grain will produce a flour highly nutritive in proportion to its bulk.

The parts of the grasses are simple and few, but Nature can so vary their forms and their arrangement that botanists recognize about four thousand species, of which over two hundred and sixty grow east of the Rockies.

The number of flowers in each spikelet varies greatly in different species. Sometimes there are a dozen or more - sometimes there is but one, with rudiments and traces of others above it. The spikelets may be ranged down one side of a main axis in compact, straight rows; they may surround the axis, as they do in "timothy" grass, forming a cylinder of bloom, or they may dangle, as the oat-spikelets do, at the tips of slender branchlets, which form part of larger sprays.

Fig. 42. - Caryop-sis of the wheat. (From the Vegetable World).

Thus the whole mass of bloom may be loose and spreading, like that of the red-top, or it may be narrow and compressed.

Sometimes the empty glumes end in a long, bristle-like point, called an awn.

Often the flowering glume is provided with an awn, which may be straight, or curved, or twisted.

The problem of providing some mode of conveyance for the seed has been solved by Nature, for various grasses, in ways as various.

The "hedge-hog" or "sand-bur" grass, common in alluvial lands, has converted its outer glumes into thorny coverings for the fruit (Fig. 43).

These catch hold of everything and everybody, and succeed so well in spreading the species that it has become a most troublesome weed.

Uncle Sam warns farmers against it, and even the text-book, forgetful of scholastic calm, dubs it vile.

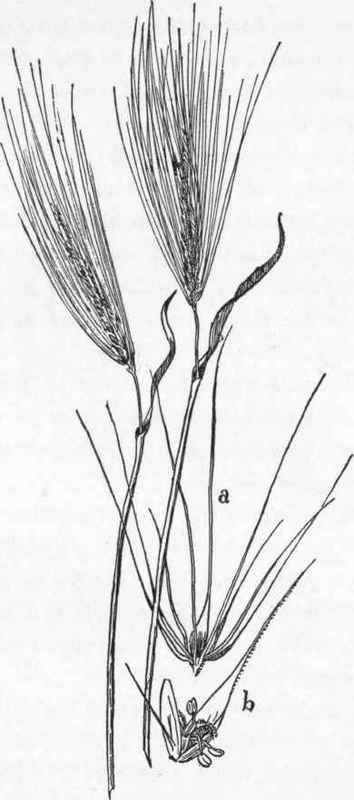

The squirrel-tail grass long ago bore three-flowered spikelets (Fig. 44). But now the side-blossoms of each trio have dwindled away, and the empty glumes below them have undergone a transformation to subserve the general good, and become long bristles, which enable the matured fruit to blow away.

As grass-pollen is carried about among the blossoms by the wind much of it is liable to be dropped and wasted.

In some species Nature makes good this loss beforehand by furnishing a double supply of the life giving grains.

Fig. 43. - Sand-bur grass (Cenchrus tribuloides).

a and 3, the bur ready to travel; c, the pair of flowers, 1 staniinate and 1 perfect. (From Bulletin No. 7 of the U. S. Department of Agriculture, 'American Grasses.")

Fig. 44. - Squirrel-tail grass (Hordeum jubatum) a, a magnified spikelet; b, a magnified flower.

The too familiar sand-bur, for instance, bears spikelets which are each a pair of flowers, one with both stamens and pistil, and one with stamens only. The blossom of the rice has six stamens, and a few grass-flowers have more than six.

But generally and typically there are three, for the grasses are distantly related to the lilies, and have no connection whatever with the rose and her kin.

The pistils of many grass-flowers do not mature till the stamens round about them are empty and shrivelled.

But the wind which has carried off the homegrown pollen will probably bring some to the waiting stigma from a neighboring plume of the same species of grass.

Unless the wind thus makes restitution for the goods he has snatched away, these grasses will bring no fruit to perfection. But if they form seed the young plants which spring from it will have the advantage which double parentage gives the seedling in its struggle for life.

The anthers and stigmas of the wheat mature together, but the flowers only expand partially, and remain open for but a quarter of an hour. The blossom appears from the glumes suddenly, scattering some - not all - of its pollen.

As the glumes close over the pistil so soon, the wind has little time in which to bring it pollen from other wheat-blossoms, and it is often obliged to use the remnant which the stamens have kept. With this it can produce good seed.

The flowering period of the whole spike of blossoms lasts four days, but since each flower blooms for but the quarter of an hour a very small proportion of them are expanded at any one time.

One of the marked characteristics of all grass-flowers is their evanescence; no blossoms are so short lived.

During their brief time of blooming a few species are visited by insects. The hospitality shown to these little guests is perhaps a last survival of an ancient family custom, a lingering memory of a time when the grasses habitually entertained a miscellaneous winged company, and the wind was by no means their only hope.

"I have often observed a small fly busy upon the anthers of various grasses,"says Muller, "and at least two species are visited by beetles".

The giants of the tribe are the bamboos, which, in their tropic homes, attain a height of fifty or sixty feet, while even those which grow in Florida gardens cast their swaying shadows on the houses' eaves.

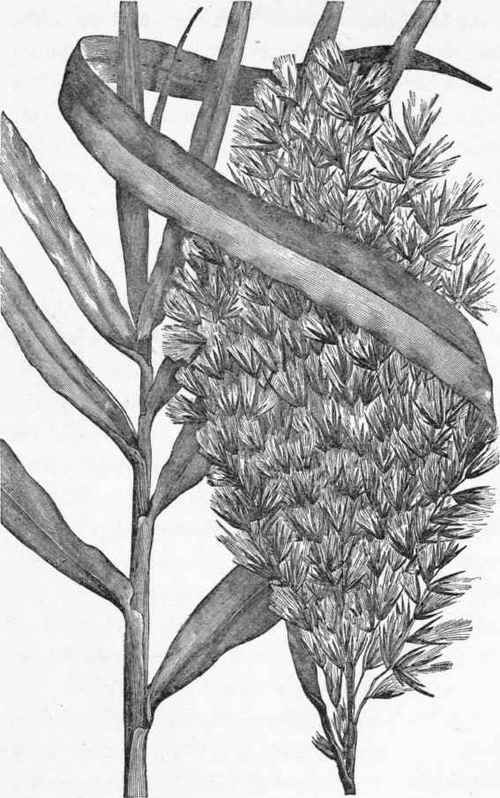

Fig. 45. - Common reed (Phragmites communis). (From Farmers' Bulletin 86, U. S. Department of Agriculture).

But these are naturalized foreigners. A great gap separates them from the tallest native grasses, the Indian corn, the wild rice, and the reeds (Fig. 45).

Few popular names are more loosely used than this term "reed." It is applied to large grasses of several species and to the cat-tail flags which are not grasses at all. But the true reed of classic story and of modern verse is the phragmites communis, whose spears of bloom, sometimes twelve feet tall, are conspicuous objects in latter summer, on the edges of ponds and streams. The plant looks, from a distance, like broom-corn.

Its many broad leaves and feathery head of blossom are swayed by the faintest breath, so that "there are not many things in Nature," says Stevenson, "more striking to man's eye than the shivering of the reeds. It is such an eloquent pantomime of terror; and to see such a number of terrified creatures in every nook along the shore is enough to infect a silly human with alarm.

Their dumb fear was noticed by the people of the classic world, who accounted for it by a legend.

There was a certain nymph called Syrinx, who was much beloved by the satyrs and the spirits of the wood.

She would have none of them, for she was a faithful worshipper of Diana and loved only the chase. In her hunting dress she looked like Diana's very self, save that her bow was of horn and Diana's was of silver.

One day, as she returned from the hunt, she was pursued by passionate Pan, who had long sighed for her.

Just as he overtook her she cried for help to her friends, the water nymphs.

They heard the prayer, and granted it, so that Pan, who had pursued a maiden, clasped only a tuft of reeds.

As he breathed a sigh the air sounded through the reeds and produced a plaintive melody. The god was charmed with the sweetness of the music. He bound together bits of reed of unequal length and made that primitive wind instrument which he called a "syrinx," in honor of the loved and lost Arcadian nymph.

But her fear dwells ever in the reeds, and so does the music of Pan. " He once played upon their foremother," says Stevenson, "and so, by the hand of his rivers, he still plays upon these later generations, and plays the same air, both sweet and shrill, to tell us of the beauty and the terror of the world".

Continue to: