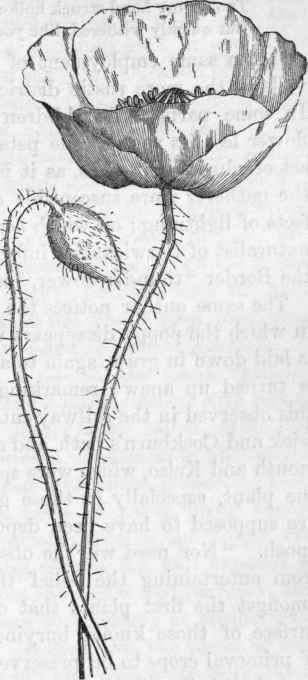

Poppy, Joan Silverpin. Papaver

Description

This section is from the book "Weeds And Wild Flowers", by Lady Wilkinson. Also available from Amazon: Weeds and Wild Flowers.

Poppy, Joan Silverpin. Papaver

Welsh, Drewg, Drewlys (P. rhceas), Cryn-ben-llyfn, Llygad y cythraul. - Anglo-Saxon, Papig. - French, Pavot, Coque-licot. - German, Mohn. - Italian, Papavero, Fico del inferno. - Spanish, Adormidera, Amapola. - Arabic, Aboo-l'-nom. - lllyric, Mak, Trava.

Linnaean

Polyandria. Monogynia.

Natural

Papaveraceae. Papaver.

Southey, in his "Doctor," tells us of the apt deceptions practised by the cooks of old, ere Soyer, Ude, or other such chefs of scientific merit, enlightened the civilized world in the refinements of their art, and abolished from our cookery books mystifications as simple and innocent as "rabbits surprised," and other metamorphoses of a like nature,* where, though the dish bore the name, the eater was the victim for whom the surprise was intended.

* It is amusing to observe how, in old cookery books, every exertion was directed to the endeavour to make the edible look like something wholly different in nature and taste; creams and fruit appearing under the guise of bacon and eggs, etc. These dishes were designated so and so surprised. We are content at present with disguising the substance of the dish we cook.

The same writer also tells us that "once upon a time" a somewhat exacting king of Bithynia being on an expedition against the Scythians, and therefore far away from the sea, and being, moreover, frozen up in the winter time, demanded for his dinner a certain small and unattainable fish called aphy. Now kings of Bithynia were not to be trifled with; aphys were not to be obtained; and, therefore, his cook, cutting out mock fish from the root of a turnip, and duly frying and salting them, powdered them well with the "grains of a dozen black poppies," and so completely deceived his Bithynic majesty, that he declared the "fish" to be unusually good.

Lord Bacon derives from the poppy a different use, when he recommends the introduction of the poppy-head into the food of little babies; and he certainly appears to have more consideration for his own peace and quiet on this occasion than for the health of the poor children. If, too, he gives it the complimentary name of "benedictum," it is rather for his own benefit; and nurses have not been behindhand in making the same discovery, when they have recourse to Daffy's Elixir, syrup of poppies, and other preparations of a similar nature.

Poppies were not always used in a furtive manner for food; as Zuinger informs us that the white-poppy (P. somniferum) - meaning probably their heads - was toasted, and eaten with honey;* an accompaniment which modern opium-eaters have probably not attempted. The Persians mix poppy-heads with their wine; and Ronsard talks of eating poppies in a salad; but this last was probably for a medicinal purpose, as he complains that even this gave him no sleep.

* "Theatrum Humanae Vitae".

It would be superfluous to refer to the medicinal properties of the poppy, which are already so well, and often too well, known in their first effects, though not sufficiently contemplated in their fearful after consequences.

In modern mythology the poppy is dedicated to St. Margaret of Antioch, for -

* * "Poppies a sanguine mantle spread For the blood of the dragon St. Margaret shed;" or, as others say, on account of their being, from their sanguine colour, emblematic of martyrdom in general. More anciently they were sacred to Ceres; doubtless from their constant occurrence in the place in which, of all others, they look most beautiful, namely, amid the golden corn, where they stand in glorious contrast with the celestial blue of the cornflower. This is, of course, the common and brilliant P. rhceas, with the petals of which the delicate tapestry-bee (Apis papaveris) drapes her cell, and of which William Turner, writing in 1551, says; "This kind is callid in English corn-rose, or red corn-rose, with us it growith moche amonge the rye and barley;" adding, "it is called Papaver erraticum in Latin - in Greek rhceas - because the flowre fallith awaie hastilie." "Nature, methinks," says Hooke, "does seem to hint some very notable virtue or excellency in this plant, from the curiosity it has bestowed on it.

First, in its flower; it is of the very highest scarlet dye, which is indeed the prime and chiefest colour, and has been in all ages of the world the most highly esteemed; next, it has as much curiosity shewed also in the husk or case of the seed, as any one plant I have yet met withall; thirdly, the very seed them selves the microscope discovers to be very curiously shaped bodies; and lastly, Nature has taken such abundant care for the propagation of it, that one single seed grown into a plant is capable of bringing some hundred thousands of seeds."*

Theocritus alludes to the use of red-poppies as love-charms:-

Common Scarlet-Poppy, Corn-Poppy, Corn-Rose. Papaver rkceas.

* "Mirographia." Linnaeus says that 30,000 seeds have been counted in the head of a single red-poppy.

"By a prophetic poppy-leaf I found Your changed affection, for it gave no sound Tho' in my hand struck hollow as it lay, But quickly withered, like your love, away;" and the same employment of the flower still prevails in the more rustic districts of our own land. In some parts little children fear to gather the flower lest its very fragile petals should fall in the act of plucking it, thus, as it is believed, rendering the gatherer more susceptible of the dangerous effects of lightning; on which account, as the veteran naturalist of Berwickshire informs us, it is called on the Border "thunder-flower," or "lightnings".

The same author notices the remarkable manner in which the poppy disappears when ploughed land is laid down in grass, again to appear when the soil is turned up anew; remarking on an example of this observed in the railway cuttings* between Berwick and Cockburn's path, and also between Tweed-mouth and Kelso, which were speedily covered with the plant, especially in those gravel knolls which are supposed to have been deposited in the glacial epoch. "Nor need we," he observes, "be hindered from entertaining the belief that the poppy was amongst the first plants that occupied the naked surface of those knolls, burying therein the seeds of primeval crops to be preserved intact until accident shall bring them up, and within the influences of vivifying agents."†

* These railway cuttings furnish considerations which botanists would do well to study; their earliest vegetation having frequently a very distinctive character.

† See "Botany of the Eastern Borders".

I must, however, enter a protest against his inference, when, in connection with this fact of their primeval burial in those knolls, he goes on to say; "there is a far distant antiquity even in one of its provincial names. In the neighbourhood of Gorden I heard this weed called Coekeno - evidently from Coch, the Celtic for red." Antique indeed, and Celtic too, this name must be, like the French Coquelicot; yet the staunchest Celtic philologer will scarcely indulge in the idea that his tongue afforded names to the wild flowers of Britain in the "primeval"* days of the glacial period, when the frozen ocean launched its mighty boulders into the very heart of our land. Had the knolls been sepulchral tumuli we might have admitted the connection.

The scarlet-poppy is one of the plants included in the discoveries of Sir John Herschell with regard to that branch of photography called anthotype, which, by a simple process, enables us to photograph certain flowers in their own juices, preserving their natural colours. A piece of paper being evenly coated with the expressed juice of the poppy, violet, stock, rose, young cereals, etc, and exposed to light, will quickly lose the tint it had received; and the same thing occurs to a watery or alcoholic infusion of the plant. If, however, the paper be submitted to the action of light, with a carefully spread flower or other object upon it, the surrounding parts only will blanch, and a perfect coloured representation of the object will remain. This blanching is to be traced to the demonstrated fact that the vital principle of vegetation prevents those changes of colour which immediately take place when that influence is destroyed. Unfortunately there is as yet, I believe, no discovered mode of fixing the representations so obtained, which, in their turn, fade away on the admission of light; but doubtless the progress of science will ere long remedy this deficiency.

* The word is that of Dr. G. Johnston himself.

The yellow horned-poppy (P. glaucum, or Glau-cium lutea) of our sandy shores - so named from the protrusion of its long and horn-like pistil - abounds also on the shores of middle and southern Europe, and on those of Virginia and Carolina, thus shewing a very marked lateral zone of geographical distribution. It is the "squabs" of the Portland islanders.

These horned-poppies however, of which we possess, in addition to the above, the following species: the scarlet horned-poppy (Glaucium Phoeniceum), and the violet horned-poppy (G. violaceum), are no longer considered genuine poppies, being separated into a group termed Glaucium; in the same manner as the following species is now recognised as belonging to the genus Meconopsis.

The Welsh poppy (Papaver, or Meconopsis Cam-bricum) is so named on account of its occurring more abundantly in the Principality than in any observed part of the world. It occurs, however, in tolerable quantity on the Pyrenees, the French Alps, and also on the river Jenisen in Russia; while in England it is found at Cheddar, and near Kendal; as also in some parts of Ireland.

The true poppies of Britain are: 1. the P. Rhcecs, already alluded to; 2. the long prickly-headed-poppy (P. argemone), which frequents similar situations, and is distinguished by the narrowness of its petals; 3. the rough round-headed P. hybridum, which occurs, though sparingly, in the chalky or sandy fields of Norfolk, Durham, Cornwall, Essex, and Kent; as well as about Ormeshead in Ireland; 4. the long smooth-headed P. dubium, which we know by its much paler hue; and 5. the white, or opium-poppy (P. somniferum), which we cannot consider to be really an indigenous plant, as it is only found in the neighbourhood of districts where it has at some time been cultivated.

I must beg to dissent from those writers who tell us that the name papaver (whence our poppy), is applied to this plant "because it is administered with pap (papa, in Celtic), to induce sleep," though I am not in the satisfactory position of being able to offer a better etymology. This, however, does not necessarily compel me to rest satisfied with a false one.

The Arabs justly term this plant aboo-l-nom, or the "father of sleep;" but it is quite beyond the limit which I have marked out for myself to enter into the very familiar subject of the produce of opium from the poppy. William Coles, in his "Adam and Eve, or the Paradise of Plants," affirms that, according to the "doctrine of signatures," a decoction of the poppy is good for all diseases of the head, "as their crowns somewhat represent the head and brain" of man.

Continue to: