House Sparrow. Continued

Description

This section is from the book "The Balance Of Nature And Modern Conditions Of Cultivation", by George Abbey. Also available from Amazon: The Balance Of Nature And Modern Conditions Of Cultivation.

House Sparrow. Continued

The Black Thread Scare (Fig. 107, C) consists of black thread attached tightly to small sticks set upright in the ground about 4 ft. apart, and the lines not more than 1 to 2 ft. asunder, crossing the threads in the case of seed-beds diagonally. For rows of crocuses, polyanthuses, carnations, etc., or peas, lettuces, winter spinach, beet, etc., it suffices to run the thread along the sides (v) just clear of the plants, and 2 or 3 in. from the ground. By those means the sparrows are frightened and the plants thrive (w); unthreaded plants adjoining are eaten off (D x).

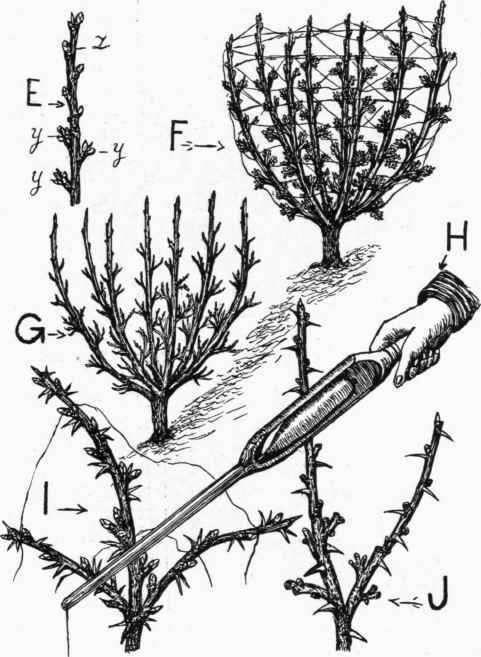

Fig. 108. - Protecting the Buds of Fruit Bushes.

E, portion of a branch of red currant with buds intact; y, spurs, usually blossom buds clustered on a short stubby shoot with a growth bud in the centre; z, terminal growth (previous summer's) with growth (narrow and pointed) and flower-buds (short and rounded). F, red currant bush rough-webbed with black thread as protection against bullfinches and sparrows. G, red currant bush from which buds taken by birds. H, Rolfe garden webber. I, portion of a gooseberry bush with buds intact and lines of black thread. J, portion of gooseberry bush from which the buds have been taken by birds.

Sparrows, also bullfinches, often denude gooseberry and currant bushes of the best buds. They may be prevented by running lines of black thread lengthwise and crosswise of the bushes, but preferably on each bush (Fig. 108, F) forming large irregular meshes by winding the thread round the tips of branches, this so annoying the birds as to ward off their attacks. This can be done with great celerity by the Rolfe "Garden Webber" ("Stott" Company, Manchester), Fig. 108, H. The cotton unwinds as fast as the stick can be passed over the bushes - ten or more times as quickly as by passing the cotton through the fingers.

Bush and pyramid plum and other fruit-trees may be rough-webbed with black thread similarly to currant and gooseberry bushes to protect the buds from sparrows and bullfinches.

Sprouting peas are sometimes protected by Pea Guards made of |-in. diamond mesh wire-netting galvanized after made, 3 ft. long, 6 in. high and 6 in. wide. In some cases mice are as troublesome as sparrows, when it may be necessary to use Mouse Proof Guards, the netting quarter-inch mesh. This mesh is also used for protecting seeds, such as those of the rose, from the depredations of mice, the guard being 12 in. wide and.6 in. high. What is known as a Strawberry Guard - a similar contrivance, but with an elliptic top, longitudinal and cross stays, ¾-in.mesh netting, 6 ft. long, 1 ft. 6 in. wide, and 1 ft. high - is used for protecting carnation "grass" from the ravages of sparrows, and also utilized for keeping blackbirds from pecking ripening strawberries, also for protecting rows of winter spinach, lettuces, etc., from sparrows. These contrivances, however, are somewhat expensive in relation to the value of the crop, and can only be indulged in by persons not estimating crop value from a commercial point of view, or growing from the standpoint of utility.

For protecting blossom buds from the ravages of sparrows and other bud-destroying birds, Mr. William E. Bear, a fruit-grower for profit, uses the following, which he finds effective: 20 lb. lime, 50 lb. flowers of sulphur, and 75 lb. of soft soap in 150 gallons of water. The sprayings are recommended to be done so freely that the trees or bushes will be well coated, as if they had been whitewashed with a brush. This is given as an example of the expense to which fruit-growers are put in order to protect their crops prospectively from the devastation partly, if not solely, due to toleration long ago overstepped in the case of the house-sparrow. Its reduction, therefore, to more reasonable numbers is essential to the successful practising of agriculture and horticulture, especially round villages and hamlets where small holdings are, or are likely to be, located, isolated farmsteads and holdings having the repressive measures to a greater extent in their own hands, though the migrations from town to country of sparrows in harvest time and sojourn there until late in autumn is well known. Any attempt at reduction must be thorough and embrace the whole country. It is little use killing sparrows in one locality, if they are allowed to multiply in surrounding districts.

Even the isolated farmstead fostering sparrows may be a serious cause of loss to the neighbouring farmer careful in destroying eggs and nests in the breeding season. In like manner a village or hamlet doing nothing but grumble may rear sparrows sufficient to re-stock neighbouring villages and hamlets where strenuous steps are taken by Sparrow Clubs to lessen the sparrow plague in their districts. But the great fostering places of sparrows are towns and centres of industry whose interests are alien to profitable agriculture and horticulture. Therefore, we propose that every Parish Council constitute a Sparrow Club with power to pay for eggs, nestlings, and adult or fledged birds, on similar lines to what obtained in most country parishes when, at the beginning and up to the middle of last century, the overseers or churchwardens paid for sparrows'heads and eggs. This must be imperative in all parishes of a district. Then the District Council, finding any special damage committed in a parish by sparrows on standing or unharvested corn crops, shall appoint a valuer to estimate the loss to the grower or growers, and the sum or sums agreed upon paid out of the rates.

Thus village and town residents would be interested in keeping down sparrows and rendering it feasible to grow corn on village allotments and small holdings.

Village or District Sparrow Clubs may appeal to some persons as most appropriate, but what good are they unless embracing the parishes, and particularly those of towns, where the sparrows are reared, as well as those where they are held in check? A club in Kent, says a Board of Agriculture leaflet, with less than twenty working members, destroyed during the three seasons (1900, 1901, 1902) over 28,000 sparrows. The Witham (Essex) Sparrow Club closed the season 1906 with a record of 36,541 sparrows killed. Three members contributed 3,000 birds each.

Of course, such results are obtained by legitimate means, such as destroying eggs and nests in the breeding season, the use of nets, chiefly "clap" and "purse," on dark nights around ricks, ivy-clad houses, and evergreen bushes where the birds roost, and by shooting flocks as they rise from standing, ripening corn, or aggregations in stubbles and about outlying corn-stacks, as well as about farmsteads, poultry-yards, etc., during the winter.

Poison, particularly poisoned wheat, is not allowed by law to be used for destroying sparrows or other birds, though Mr. F. Smith in his paper on "The Fruit Grower and the Birds," says:

"For reducing the number of sparrows the best thing he has known was Harding's prepared wheat. It would not kill anything larger than a sparrow or mouse - it would not kill rats or poultry. But the Government of the day brought in a Bill making it illegal to poison wheat in any way. Still something might be done by appointing a certain number of men to kill sparrows by this means by permission of the Board of Agriculture."

Notwithstanding legislative enactment, poisoned wheat is used for destroying sparrows, and not only by those evasive of law through privacy of location, but with countenance of persons wishful of small bird riddance, as shown by the following excerpt from the Daily Chronicle, April 30, 1907:

Continue to: