II. England's "Benevolent Despot"

Description

This section is from the book "Modern England", by Justin McCarthy. Also available from Amazon: Modern England Before The Reform Bill.

II. England's "Benevolent Despot"

Let us see what was the condition of England at the time when Napoleon's career was drawing to its close. So long as the great war was going on England kept a united front to the enemy. But of course there were internal divisions of opinion. There was in domestic affairs what we should call a reform policy, and also an anti-reform or conservative policy. While the war was raging men's thoughts were turned away from anything like a systematic prosecution of the reform cause, and it would have been impossible to get the British Parliament to pay any serious attention to proposals for an improved financial system, for the equalisation of burdens on the different tax-paying classes, or for an improvement in the franchise and the general representative system. But there always were some men who did their very best to keep the reform light burning, even through the most agitating hours of continental war. The great leader of the Conservative party was William Pitt, son of the Earl of Chatham - public opinion is still divided as to which was the greater man, the elder Pitt or the younger. William Pitt the younger was undoubtedly one of the greatest statesmen and parliamentary orators England has ever known. He must be classed with Conservative statesmen, because some of the most momentous passages of his career were those in which he stood forth as the opponent of all projects of reform. Yet we know that Pitt was not by intellect or by nature an enemy of reform; he had himself foreshadowed and promised to favour some of the best reforms which it was left to other statesmen to accomplish - reforms which in his later days he had to oppose. Those later days were cast in the worst of all times for a reforming statesman. The thoughts of the country were absorbed in the war, and the war was sincerely regarded by many honest, stolid men, like George III. himself, as a calamity directly brought about by the crazy enthusiasm of French reformers. It was part of the creed of every country gentleman who followed Pitt in those days that if the King of France had only refused to listen to any wild talk about liberty and equality, about the abolition of class prerogatives, and the emancipation of public opinion - if he had only refused to listen to such ravings and ordered his cannoneers to do their duty, the Revolution would have been destroyed in its birth, and there would have been no occasion for a war with England. Therefore, these same country gentlemen who followed Pitt fully believed that every concession made to the demands of reformers in England would be nothing but an invitation for indulged reform to feast its thoughts on revolution.

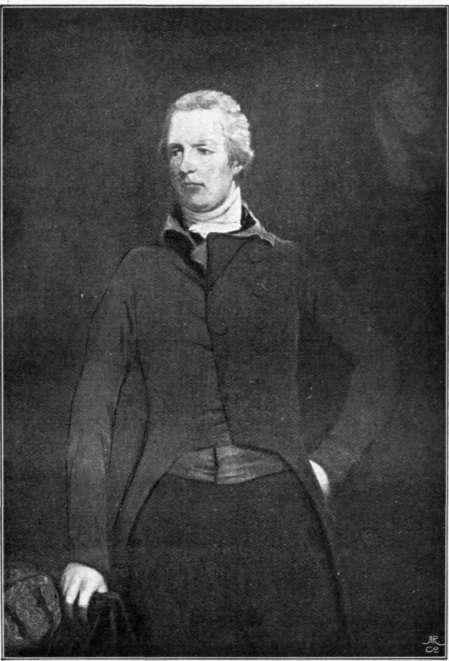

William Pitt. (1759-1806).

All these seem to us very absurd ideas now, but we must remember that they were ideas which at one time got possession of and obscured the greatest political intellect of the day, the intellect of Edmund Burke. At all events, the King on the throne and the gentlemen in the provinces were of one mind on this subject, and they formed a power too strong for even Pitt to bear up against if he had been inclined to make the experiment. He was not during his later years inclined to make any such experiment. The war was too much for him; he died of it almost as literally as if he had fallen upon the field of battle. He never recovered from the shock which was given to him by the news of the great defeat of the allied powers by Bonaparte at Austerlitz. His friends said that from that time the "Austerlitz look" was always on his face.

Pitt's great opponent was Charles James Fox. It is a curious fact that in two succeeding generations there should have been in the English Parliament a Pitt fighting against a Fox. But though the second Pitt might well challenge comparison with the first, the second Fox was incomparably superior to his father, the elder Fox. Charles Fox was probably the greatest debater ever known to the House of Commons. He cannot be called the greatest orator while we remember Bolingbroke and the two Pitts and Sheridan, and in a later day Bright and Gladstone. But bearing all these illustrious names in mind the present writer still adheres to the opinion that Fox was the greatest of English debaters. His mind was informed by a generous enthusiasm for peace and for liberty.

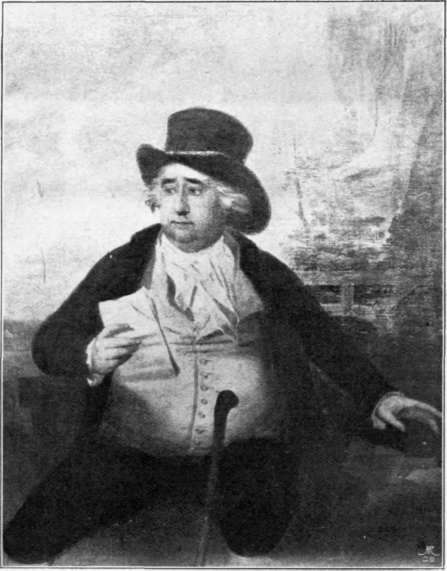

Charles James Fox. (1749-1806).

Thomas Moore, the Irish poet, well described him as an orator " On whose burning tongue Truth, peace, and freedom hung". His bold, comprehensive mind surveyed the whole field of possible reform, and welcomed with eager sympathies every proposal which bore with it any practical promise of success. He was a reformer not merely for England, but for Ireland, for India, and for England's great colonial possessions. He, too, like his rival, William Pitt, was removed from the front of the political battle long before the fall of Napoleon gave the English people the chance of attending soberly to their own domestic affairs. One of the most brilliant speakers in the House of Commons was Richard Brinsley Sheridan - also the greatest dramatic author the English stage had known since the comedies of the Restoration. Sheridan's lustre as a parliamentary orator has somewhat dimmed, perhaps, of late years. No really authentic reports of his great speeches are preserved, and we find it hard to believe that even his famous "Begum" speech, the speech attacking the administration of Warren Hastings in India, can have deserved the strong praise which was undoubtedly given to it by all those who heard it, no matter what their political opinions - a praise which set it above any oration delivered in Parliament before. Sheridan clung to the reform cause even at the darkest hours of its history. Burke, who through the best years of his life had been a Whig, or what we should now call a Liberal, had quarrelled with Fox over the French Revolution, and had declared in the House of Commons that the friendship between them was extinguished for ever. Sheridan remained fast to his old principles, but it was not given to him any more than it was to Fox to see a marked success accomplished in the difficult field of reform.

Continue to: