Balance. Part 5

Description

This section is from the book "The Principles Of Interior Decoration", by Bernard C. Jakway. Also available from Amazon: The Principles of Interior Decoration.

Balance. Part 5

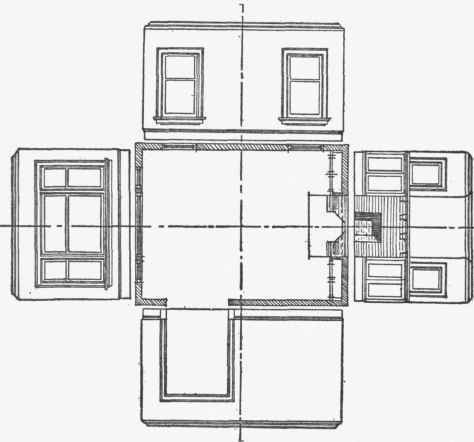

While the balance between opposite ends and opposite sides of a room must be clearly felt, it will be the more pleasing in the degree that it is occult rather than formal. No one wants to see the two sides of a room exactly alike; yet we cannot be free from a sense of unrest unless there is an easily apprehensible equality between the total weights of the two sides. In practice the student will find it of the utmost value to draw an accurate floor plan and elevations of his room, to a scale of one inch, or at least of one-half inch, to the foot, according to the method indicated in Figure 41. With the size and shape of the room and the distribution of voids and masses thus clearly before him, he can pencil in, according to the same scale, outlines to represent the rugs, furniture and pictures and other elements that he purposes to use in the room. These pieces can be arranged and rearranged until their distribution finally seems satisfactory with reference to both axes of the room. The effectiveness of the device can be increased by washing in the principal colors, and by folding up the four elevations to form enclosing walls.

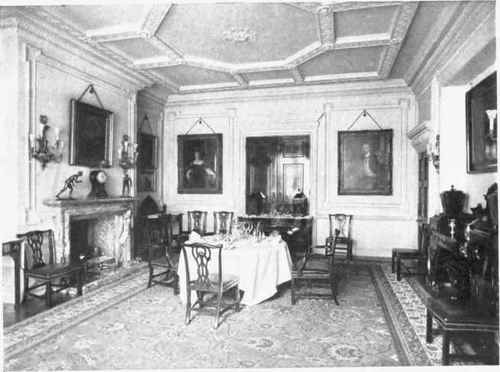

Plate VI. - A very carefully balanced room, to be studied in connection with the chapters on Balance, Proportion, and The Elements of Beauty. Note, for example, how the rectangular wall spaces and the round table have been related by the plaster relief ceiling.

Figure 41. - Typical floor plan and elevations, drawn to a very small scale. The layman will probably find it more helpful in practice to omit the part of the drawing that shows the wall thickness, and to start the four elevations from the inner floor line.

It would be fruitless to extend further the discussion of balance as it conditions the arrangement of the movables in a room, since such a discussion could of necessity deal only in generalities, while the complex of personal and architectural factors, different for each room, makes the problem presented by each room unique. The principles laid down indicate the general method of arrangement, and innumerable illustrations in books and magazines afford a wide field for suggestive study. This study will be made more fruitful by following the plan outlined above; but a perfect or even a fairly excellent arrangement can rarely be attained except as the result of much experiment. In most of the processes of house-furnishing experiment is costly, since it involves discarding some things and buying others. In experimenting with effects of balance no expenditure is demanded save that of time and effort, while the gains, both in the beauty of the room and in the growth of creative power in the decorator, are always considerable and frequently astonishing.

The balance of color is qualitative rather than quantitative. A small area of a given color in one situation will effectively balance a large area in an opposing situation. Thus a small chair will balance in color a large davenport, as a lamp shade or a vase will balance a pair of hangings or a table cover. Color balance will be treated at greater length in the chapter on color harmony, while the balanced distribution of light and shade so essential to the comfort and distinction of a room will be discussed in the following chapter.

Continue to: