The Story In A Newspaper

Description

This section is from the book "The Wonder Book Of Knowledge", by Henry Chase. Also available from Amazon: Wonder Book of Knowledge.

The Story In A Newspaper

Among the marvels of machinery of the present day there are none more complicated and bewildering in appearance than that by which the news of the world is sent adrift within the daily newspaper and none more marvelously effective in its operation. If we go back to the days when the seeds of the modern press were planted, we find them in the hand-printing done by the Chinese with their engraved blocks, and with the simple press used by Gutenberg about 1450, when he printed the first book from movable types.

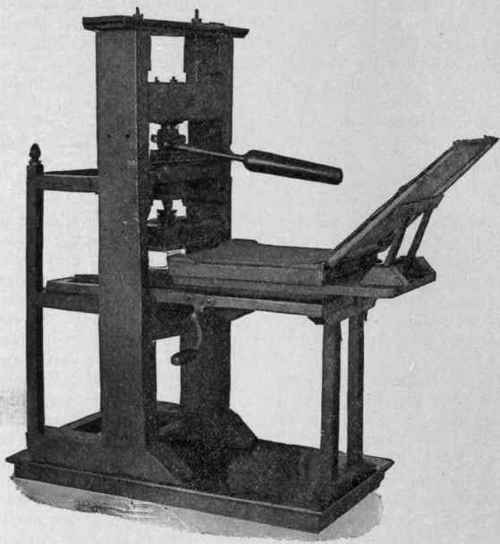

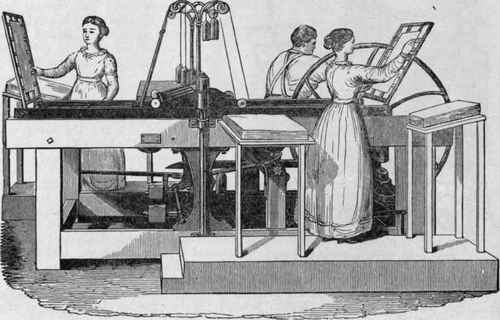

His press consisted of two upright timbers held together by cross pieces at top and bottom. The flat bed on which the types rested was held up by other cross timbers, while through another passed a wooden screw, by the aid of which the wooden "platen" was forced down upon the types. The "form" of type was inked by a ball of leather stuffed with wool, the printer then spread the paper over it, laying a piece of blanket upon the paper to soften the impression, after which the screw forced the platen down on the paper and this on the type. This press was not original, since similar cheese and linen presses were then in use.

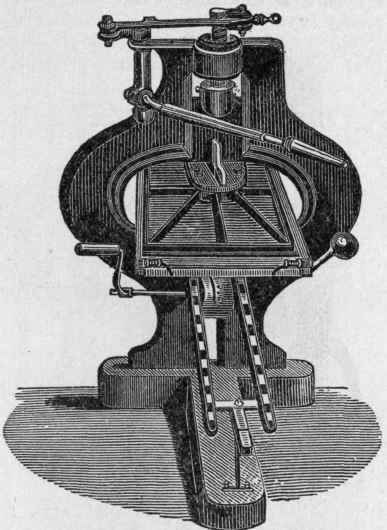

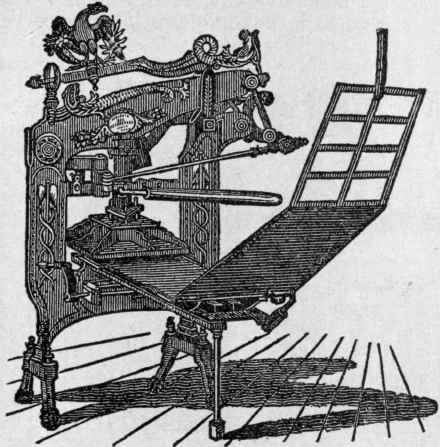

For 150 years this crude method of printing continued in operation, the first known improvement being made by an Amsterdam printer about 1620, he adding a few parts to render the work more effective. Such was the simple press still employed when Benjamin Franklin began his work as a printer a century later. In 1798 the Earl of Stanhope had a cast-iron frame made to replace the wooden one and added levers to give more power to the pressman. Woodcuts were then being printed and needed a stronger press.

We must go on with the old Gutenberg method and its tardy improvements, for another century, or until about 1816, when George Clymer, a printer of Philadelphia, did away with the screw and employed a long and heavy cast-iron lever, by the aid of which the platen was forced down upon the type, the operation being assisted by accompanying devices.

The Blaew Press, 1620.

*Illustrations by courtesy of R. Hoe & Co.

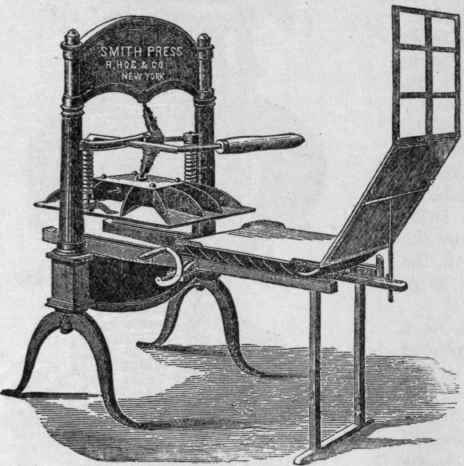

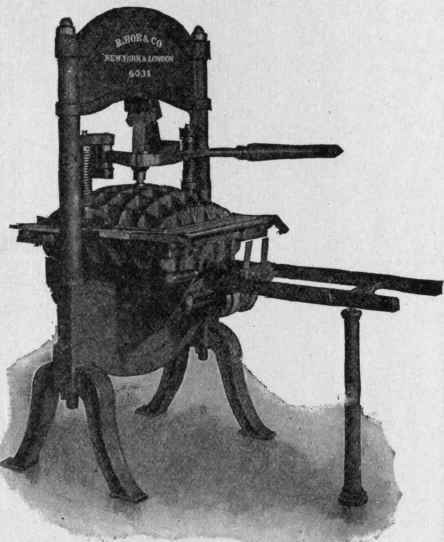

As will be seen, the growth of improvements had until then been very slow. From this time forward it became far more rapid, some useful addition to the press being made at frequent intervals. The "Washington" press, used at this time by R. H. Hoe & Co., of New York, embodied these improvements, and became one of the best hand-printing presses so far made. The first steam-power press was introduced by Daniel Treadwell, of Boston, in 1822, the bed and platen, or its successor, the cylinder, being used in these and in the improved forms that followed until after the middle of the century.

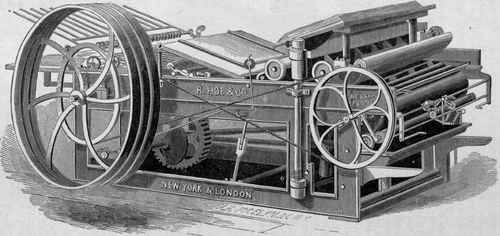

The idea of replacing the platen by a cylinder was not a new one. It was employed in printing copper-plate engravings in the fifteenth century, a stationary wooden roller being employed, beneath which the bed, with its form and paper, was moved backward and forward, a sheet being printed at each movement. With this idea began a new era in the evolution of the printing press. A vast number of patents have since been issued for printing machines in which the cylinder is connected with the bed and later for the operation of two cylinders together, one holding the form of type and the other making the impression. But all these were for improvements, the underlying principle remaining the same. The conception of a press of this character in which the paper was to be fed into the press in an endless roll or "web" goes back to the beginning of the nineteenth century, though it was not made available until a later date.

Stanhope Press, 1798.

Clymer's Columbian Press, 1816.

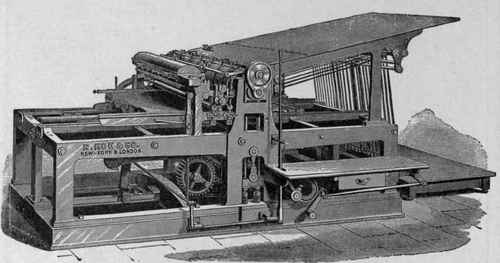

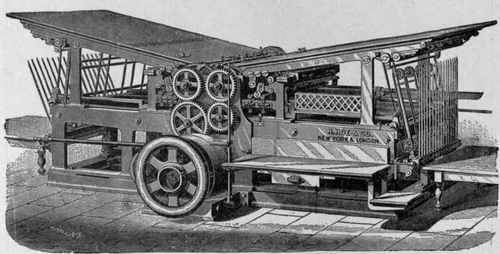

Meanwhile, however, patent after patent for the improvement of the cylinder press were taken out and the art of printing improved rapidly, the firm of Hoe & Co. being one of the most active engaged in this business, the United States continuing in advance of Europe in the development of the art. The single small cylinder and double small cylinder introduced by this firm proved highly efficient, the output of the former reaching 2,000 impressions per hour, while the double type, used where more rapid work was needed, yielded 4,000 per hour.

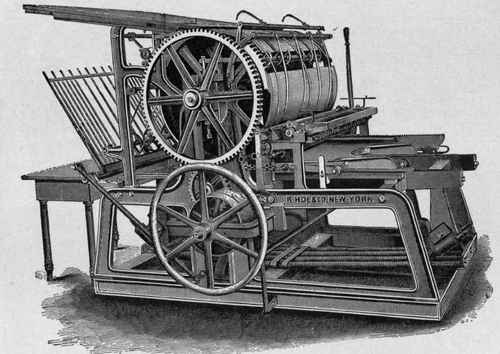

But the demands of the newspaper world steadily grew and in 1846 a press known as the Hoe Type Revolving Machine was completed and placed in the office of the Public Ledger, of Philadelphia. By increasing the number of cylinders the product was rapidly added to, each cylinder printing on one side 2,000 sheets per hour.

In 1835 Sir Rowland Hill suggested that a machine might be made that would print both sides of the sheet from a roll of paper in one operation. A similar double process had been performed for many years in the printing of cotton cloth. This remained, however, a mere suggestion until many years later, and the one-side printing continued. But, by adding to the number of cylinders, a speed of 20,000 papers thus printed was in time reached.

To prevent the possible fall of types from a horizontal cylinder, the vertical cylinder was introduced by the London Times, but this danger was overcome in the Hoe presses, and by the subsequent invention of casting stereotype plates in a curve the final stage of perfection in design was reached. In 1865 William Bullock, of Philadelphia, constructed the first printing press capable of printing from a web or continuous roll of paper, knives being added to cut the sheets, which were then carried through the press by tapes or fingers and delivered by the aid of metal nippers. There were difficulties in this series of operations, but these were overcome in the later Hoe press, in which the sheets were merely perforated by the cutter, and were afterward fully separated by the pull of accelerating tapes.

Peter Smith Hand Press, 1822.

Treadwell's Wooden-Frame Bed and Piaten Power Press, 1822.

The old-time rag-paper had disappeared for newspaper work, being superseded by wood-pulp paper, the cheapness of which added to the desire to produce presses of greater speed and efficiency. It was also desirable that papers should be delivered folded for the carrier, and this led to the invention of folding machines, one of the earliest of which, produced in 1875, folded 15,000 per hour.

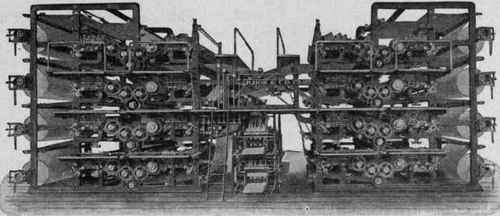

We have in the foregoing pages told the main story of the evolution of the printing press from the crude machine used by Gutenberg in 1450 to the rapid cylinder press of four centuries later. There is little more to be said. Later changes were largely in the matter of increase of activity, by duplication and superduplication of presses until sextuple and octuple presses were produced, and by adding to the rapidity and perfection of their operation, and the extraordinary ingenuity and quickness with which the printed sheets were folded and made ready for the convenience of the reader. Sir Rowland Hill's dream of a press which would print both sides of the paper at one operation in due time became a realized fact, while vast improvements in the matter of inking the forms, and even the addition of colored ink by which printing in color could be done, were among the new devices.

What we have further to say is a question of progress in rapidity of action rather than of invention. The 20,000 papers printed per hour, above stated, has since been seen passed to a degree that seems fairly miraculous. The quadruple press of 1887 turned out eight-page papers at a running speed of 18,000 per hour, these being cut, pasted and folded ready for the carrier or the mails. Four years later came the sextuple press (the single press six times duplicated) with an output of 72,000 eight-page papers per hour, and in a few years more the octuple press, its output 96,000 eight-page papers per hour. Larger papers were of course smaller, but its capacity for a twenty-page paper was 24,000 per hour.

As may well be conjectured, the twentieth century has had its share in this career of progress, the perfected press of 1916 being credited with the astounding output of 216,000 eight-page papers in an hour, all folded, cut and counted in lots.

Washington Hand Press, 1827.

Isaac Adams' Bed and Platen Press, 1830.

W. ROBERTS.SG.N.Y. SINGLE LARGE CYLINDER PRESS, 1832-1900

Single Small Cylinder Press, 1835-1900.

Double Cylinder Press, 1835-1900 These presses were built up to 1900 and this picture shows the latest design brought out about 1882..

Double Octuple Newspaper Web Perfecting Press, 1903.

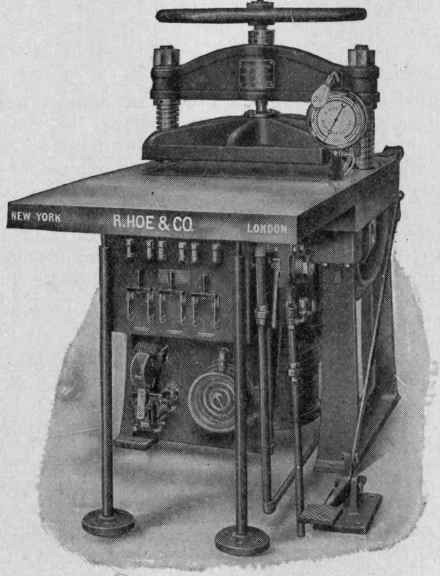

Electric-Hea.ted Pneumatic Matrix-Drying Machine, 1911.

Where part of the pages are printed in three colors this press has still a running speed of 72,000 per hour. This machine is composed of 27,100 separate pieces, it being 47 feet long, 8 feet wide and 13 feet high, while such a mighty complication of whirling wheels and oscillating parts nowhere else exists.

A word more and we are done. To feed such giant presses the old hand method of setting and distributing type has grown much too slow. The linotype machine has added greatly to the rapidity of this centuries-old process. To this has been added the later monotype, of similar rapidity, while type distributing has become in large measure obsolete, the types, once used, going to the melting pot instead of to the fingers of the distributors.

Continue to: