The Copy-Modify-Merge Solution

Description

This section is from the "Version Control with Subversion" book, by Ben Collins-Sussman, Brian W. Fitzpatrick and C. Michael Pilato. Also available from Amazon: Version Control with Subversion.

Subversion, CVS, and many other version control systems use a copy-modify-merge model as an alternative to locking. In this model, each user's client contacts the project repository and creates a personal working copy—a local reflection of the repository's files and directories. Users then work simultaneously and independently, modifying their private copies. Finally, the private copies are merged together into a new, final version. The version control system often assists with the merging, but ultimately, a human being is responsible for making it happen correctly.

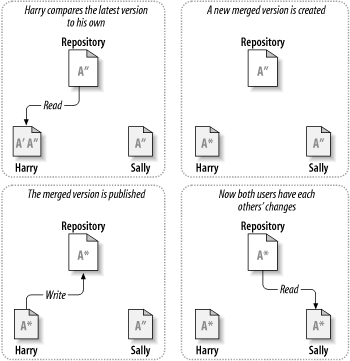

Here's an example. Say that Harry and Sally each create working copies of the same project, copied from the repository. They work concurrently and make changes to the same file A within their copies. Sally saves her changes to the repository first. When Harry attempts to save his changes later, the repository informs him that his file A is out-of-date. In other words, that file A in the repository has somehow changed since he last copied it. So Harry asks his client to merge any new changes from the repository into his working copy of file A. Chances are that Sally's changes don't overlap with his own; once he has both sets of changes integrated, he saves his working copy back to the repository. Figure 1.4, “The copy-modify-merge solution” and Figure 1.5, “The copy-modify-merge solution (continued)” show this process.

But what if Sally's changes do overlap with Harry's changes? What then? This situation is called a conflict, and it's usually not much of a problem. When Harry asks his client to merge the latest repository changes into his working copy, his copy of file A is somehow flagged as being in a state of conflict: he'll be able to see both sets of conflicting changes and manually choose between them. Note that software can't automatically resolve conflicts; only humans are capable of understanding and making the necessary intelligent choices. Once Harry has manually resolved the overlapping changes—perhaps after a discussion with Sally—he can safely save the merged file back to the repository.

The copy-modify-merge model may sound a bit chaotic, but in practice, it runs extremely smoothly. Users can work in parallel, never waiting for one another. When they work on the same files, it turns out that most of their concurrent changes don't overlap at all; conflicts are infrequent. And the amount of time it takes to resolve conflicts is usually far less than the time lost by a locking system.

In the end, it all comes down to one critical factor: user communication. When users communicate poorly, both syntactic and semantic conflicts increase. No system can force users to communicate perfectly, and no system can detect semantic conflicts. So there's no point in being lulled into a false sense of security that a locking system will somehow prevent conflicts; in practice, locking seems to inhibit productivity more than anything else.