Botanical Hints For Flower Painters

Description

This section is from the book "Arts & Crafts Magazine Vol1-2", by Hutchinson & Company.

Botanical Hints For Flower Painters

The flower painter should know a little botany, just as the figure painter should know a little anatomy, if only enough to distinguish readily the more important parts and to avoid being puzzled by the strange appearances which they sometimes take on. From root to flower each part of a plant is to be studied. It should be noted, in the first place, that all plants are double; that from a point of union at or near the ground the roots radiate downward and the branches or leaves upward. In addition to this there is a right and left symmetry or balance, as in the case of animals, though not nearly so marked. This last is due to gravity; and it will often be

Pen Studies Of Pansy Blossoms By Em- Hallowell remarked that the plant or tree, after nearly losing its balance by branching in one direction, ensures its equilibrium and relieves the strain on the roots by branching just as far on the opposite side.

The stems of plants take various names, according to the way in which they act toward gravity. The stem of a plant which grows upright is called "erect"; if it trains along the ground, like winter-green, it is called "procumbent"; "ramping" when it climbs, like ivy; "clasping" when it attaches itself to its support by tendrils, like the vine; and "twining" when it winds around its support, like the morning-glory or the hop.

Of leaves there are many different kinds, which the student will soon learn to distinguish at sight bv what an artist would call their " character." But mistakes as to this character will be less likely to occur if he notes that it depends chiefly upon two matters. One is the "venation" of the leaf; that is to say, the arrangement of the veins or nerves that run through and support its softer parts; and the other is the way in which it is attached to the stem. If it has a long leaf-stalk, or "petiole," it is "petiolated." If it starts direct from the stalk itself it is "sessile," or "seated." Leaves are "compound" when from a common leaf stalk others spring, as in the case of the ailanthus. Frequently it happens that simple leaves look very much like these; but the single leaflet cannot in these cases be pulled apart from the central leaf stalk without tearing it. Such leaves as that of the chestnut, which are among those that look compound, but are simple, are called "palmate," because they present something of the appearance of a hand with the fingers open. The commonest type of venation shown in such leaves, as those of the rose, the elm, the beech, is "feather-veined." All grasses, including the grain-producing sorts and the bamboo, are "parallel-veined." When there is a network of fine veins, as in the ranunculus, the leaf is "net-veined." There are often small leaflets attached to the base of the leaf-stalk, as in the rose. These arc called "stipules." And there are leaflike appendages to some flowers without any distinct venation, which are called "bracts."

A flower is usually a good deal more complex than people who have not given any particular study to it suppose it to be. To the landscape painter it is only a dot of blue, or red, or yellow that enlivens the green of his foreground. But to the flower painter it is a beautiful piece of organic form, deserving to be studied in detail and with attention. Again, there are flowers which the botanist recognises as such, although they are nothing but little bunches of yellow or greenish threads, but which have little or no attraction for the flower painter. It is well for him to know, however, that these little threads are among the essential parts of every flower. Those with little brownish or yellow heads attached are the "stamens." The heads are the "anthers," and contain the "pollen," the fine, dust-like substance which fertilizes the seed-vessel. Among the stamens usually stands the " pistil," with a flat, viscous head, which catches the pollen as it falls from the anthers. The pistil, though very small, is a hollow tube opening into the "ovary" or seed-vessel, at the base of the flower, and which, ripening, becomes the fruit. The coloured leaves, called "petals," surrounding these organs, are not essential to the flower. They serve only to protect these essential parts and to attract insects, which carry the pollen from plant to plant. Wherever the little yellow threads show, therefore, between the petals, they ought to be indicated, not only because they look pretty, as they often do, but because of their importance. The whole flower, including the petals, which, taken together, are called the "corolla," is most commonly seated in a little greenish cup called the "calyx." Sometimes it happens that the calyx is not green, but brightly coloured, as in the fuchsia, and sometimes it is hard to distinguish it from the corolla, as in all lilies.

Sketches or pictures on canvas should not be permitted to remain long unmounted. If there is not sufficient margin to them to permit their being stretched, they can be mounted on stretched canvas by any framemaker. To mount them yourself, it is only requisite that your glue be quite fluid and evenly distributed over the back, so that all parts are covered. In applying the picture to its backing, press it smooth, and it will sit properly and without inequalities. Any canvas with oil colours on it is liable to crack if not kept stretched. It may be accidentally doubled or broken, or may curl up as it hangs on the wall, but in one way or another it is sure to be injured unless a stretcher is provided to keep it permanently flat.

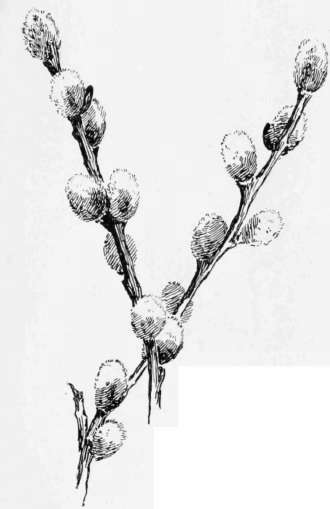

Catkins Pen Study By E. M. H.

If you find your paper rumpling, do not be discouraged; it will dry smooth, or very nearly so. If, when dry, it is still wrinkled, apply a hot iron to the back, as if it were a handkerchief, but, of course, wait until the work is dry before doing so.

Continue to: