Music And Painting. Part 3

Description

This section is from the book "Pueblo Crafts", by Ruth Underhill. Also available from Amazon: Pueblo Crafts.

Music And Painting. Part 3

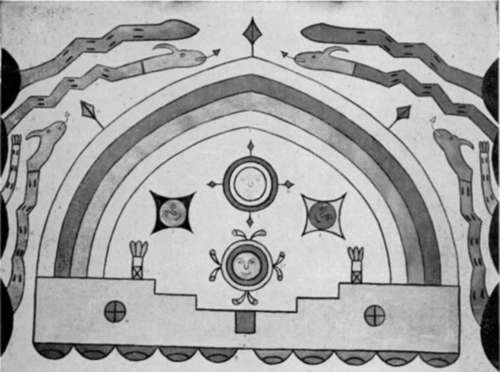

Modern students have done an amazing work in peeling off these layers glued to cloth and have preserved each one. When the pictures finally stood out, in their soft, earth colors, they revealed dancing figures like those seen in pueblo plazas today. The illustration (VI-2) shows one of these figures at the left, with kilt and white sash, mask and head feather. The bird at the center is a shape that still decorates pueblo pots. Plate VI-3 is a more formal design. Here a prehistoric Jemez artist has represented the arching rainbow and scalloped clouds which appear in pueblo ceremonies to this day. Guarding them are the horned water serpents, pueblo symbols of rain and blessing. Anyone who has seen Navaho sand paintings might almost mistake this for one of them. He will wonder again just when and how the newcomers from the north began to use pueblo designs in working out an art of their own.

Plate VI-9, Kiva painting of the Jemez universe (pre-historic).

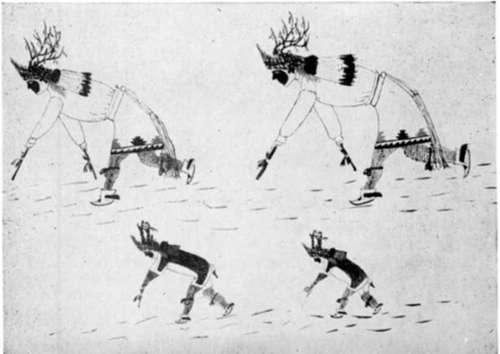

Plate VI-4. Deer and antelope dancers (Alfredo Montoyo).

Ancient pueblo paintings were on walls or rock. There were no small movable ones until the white men brought paper. When this new material came, there was a sudden burst of activity such as often happens, when skilled workers have a chance at better tools One day in 1910 white scientists noticed a San lldefonso man drawing pictures on the smooth firm ends of a cardboard box. The picture (Plate VI-4) shows the kind of work done by one of these early artists, Alfredo Montoyo. It is the deer dance at San lldefonso, with every detail clear as a jewel.

That was the pueblo style and it is to this day. We can see the careful drawings of feathers and embroidery, fine as a Persian miniature. We note there is no background, not even a line to show where sky and earth meet. The same is true of Russian icons and of Chinese scrolls. It was true of European paintings, too, some centuries ago. With pueblo paintings, the bright little figures always stand out in space with nothing to show in what world they move. They have no shadows. Nor does the artist measure space by making the figures smaller when they are far away. Look at the charming picture of the eagle dance by another of the early painters, Awa Tsireh of San lldefonso. (Plate VI-5) All the singers are the same size, whether near us or not. If the colors could be shown, they would be equally bright, not melting into blue distance as they do with white paintings.

Plate VI-5. Eagle dance (Awa Tsireh).

Awa Tsireh was one of three pueblo boys taken into the employ of the School of American Research. Thev were not trained. The white scien-tists only gave them colors and time, hoping to see pueblo ideas flower in a new and different art. They were rewarded for all three artists are now famous. Plate VI-6 is a scene by the Hopi, Fred Kabotie, now teaching his countrymen in an Indian school. We find that he has decided to use perspective in the white man's manner but his "Little Pine Dance" has the same brilliance, clearness, and dignity which belongs to all pueblo paintings. The next two illustrations (Plate VI-7 and VI-8) are by Velino Herrera, (Ma-pi-wi) of Zia pueblo. Ma-pi-wi has illustrated several books by this time and the cover of this volume shows how well. Visitors from all over the country are now having a chance to see his buffalo hunt and his dancing figures which seem to move in a world outside time and space, in a splendid mural which he completed in 1938, in the Department of the Interior at Washington, D. C.

Plate VI-6. Little Pine ceremony (Fred Kabotie).

Plate VI-7. The Indian World (Ma-pi-wi).

Plate VI-8. Firing pueblo pottery (Ma-pi-wi).

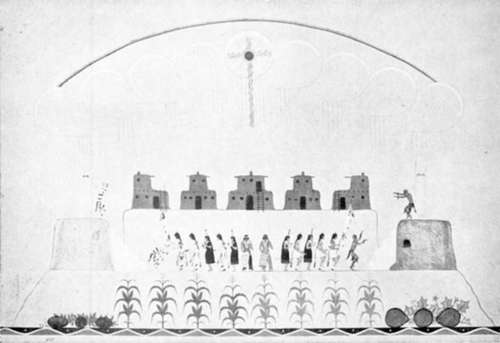

Plate VI-9. Eagle dancers of Cochiti (Tonita Pena).

Numbers of pueblo painters have followed these pioneers. If you visit San lldefonso, (Plate VI-10) now the pueblo art center, you will be led to house after house where delicate water colors are propped against the whitewashed wall. At the weekly market in Santa Fe the graceful shapes of antelopes, hunters, and dancers stand waiting for sale with the artists or their families smiling beside them. Some of the artists are women (Plate VI-9) who never painted human figures in the old days. That work, done in the kiva, was for men, while women never got for from the lines and angles of their pot designs. Now Tonita Pena and several others paint charming groups of bright shawled women, dancing, bringing food and making pottery. Pop Chal-lee of Taos is famous for her leaping antelopes.

White experts have become aware of this new art. There have been exhibitions in New York, Chicago, even in Europe. Collectors are buying the paintings, and the young artist can now see a possibility never thought of before, that of really supporting himself by his art. Since 1933 the Santa Fe Indian School has had an art department and now Hopi High School at Oraibi has one. They are under Indian teachers who work to bring out the pueblo feeling for color, for accuracy, for dignity. For centuries this feeling has been expressing itself in the arrangement of ceremonies, the painting of pottery and headdresses. Now it has further opportunities and a new style is being brought into American Art.

Plate VI-10. Sun-buffalo dancer, San lldefonso (Wo-peen).

Continue to: