The Human Eye

Description

This section is from the book "Warne's Model Housekeeper", by Ross Murray. See also: Larousse Gastronomique.

The Human Eye

From Professor Pepper's " Cyclopedic Science Simplified?

" This elaborate and wonderful work of the Creator, built up of the usual constituents of animal substances, viz. - albumen, gelatine, fibrine, with a little fatty matter - all marvellously shaped and fitted to their purposes,, represents an optical instrument which transcends every contrivance made by the hand of man. The camera obscura is the nearest approach to an imitation of the eye. It is fitted with a double-convex lens; the rays of light thrown off from any object placed before the apparatus are brought to a focus, and received upon a sheet of paper or piece of ground glass. In the eye the same result is brought about by the refraction of light in the crystalline lens and the other humours; the rays are brought to a focus, and impinge upon a nerve, spread out as a delicate network to catch the beams, and to vibrate in sympathy with those exquisite undulations which cause the propagation of light, and thus to produce the sensation of vision. Anatomists have given this organ their most careful attention, and pub-lished elaborate drawing of the various parts of the eye.

By the permission of Messrs. Chadburn, of Sheffield, a copy of their instructive diagrams of the eye is added.

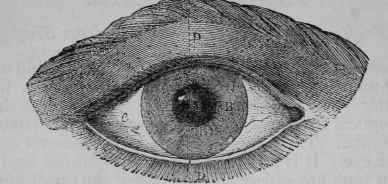

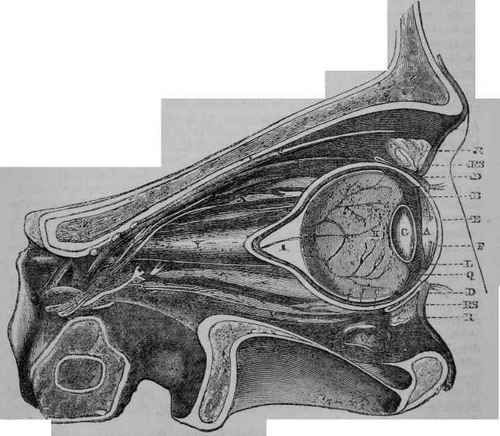

A. The Pupil, or circular opening in the iris, capable of being con-tracted or enlarged, according to the amount and intensity of light.

B. The Iris, a flat circular membrane, of a grey, blue, or black colour, forming the anterior and posterior chambers of the eye. It performs the same functions as a diaphragm in an optical instrument.

C. The Sclerotic Coat, a tough white membrane, to which the muscles for moving the eyeball are attached.

D. The Eyelids, containing the tarsal fibro-cartilages.

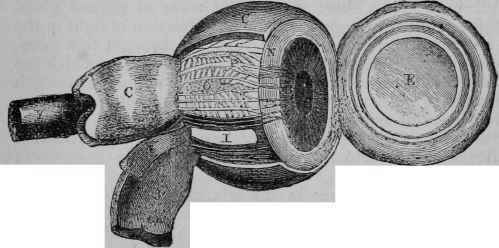

E. The Cornea, composed of tough transparent laminae, forming the front of the eye; the first surface, where the rays of light are refracted. Some anatomists have considered the sclerotica and cornea as one and the same, and have termed the cornea the transparent, and the sclerotica the opaque cornea.

F. The Aqueous Humour, contained in a delicate membrane filling the space from the cornea to the crystalline lens. The space occupied by this humour is divided into two parts by the iris, forming, as shown at B, the anterior and posterior chambers of the eye.

G. The Crystalline Lens, contained in a transparent membrane called the Capsule, the principal refracting medium of the eye. The capsule adheres by its edge to the ring-shaped body called the Ciliary Circle or ligament, N.

H. The Vitreous Humour, contained in the hyaloid membrane - a jelly-like substance, resembing the white of an egg, filling the body of the eye.

I. The Retina, a membrane which receives the impression of light, and transmits it to the brain through the optic nerve, K.

J. The Choroid Coat, a delicate membrane lining the sclerotica, covered on its inner surface with a black substance {pigmentum nigrum, resembling the colouring matter of the negro's skin) contiguous to the retina. The choroid, by its vascular tissue, serves to carry the blood into the interior of the eye.

Fig. 1. The Human Eye.

Fig. 2. The Eyeball, showing the Coats, etc., of the Eye.

Fig. 3. Longitudinal Section of the Eye and Orbit through the dotted lines on Fig. 1.

K. The Optic Nerve.

L. Canal of Petit.

M. Central Artery of the optic nerve.

N. Ciliary Circle or ligament.

O. Ciliary Nerves.

P. Vasa Vorticosa.

Q. The Ciliary processes.

R. Tunica Conjunctiva.

R S. Tunica Conjunctiva collapsed, as when the eye is closed.

S. Elastic Muscle of the Eyelid.

T. Elastic Muscle of the Eye.

U. Superior Oblique Muscle.

V. Depressive Muscle of the Eye.

W. Section of Oblique inferior Muscle.

X. Nerves and Arteries.

Y. Tube conveying the optic nerve to the brain.

Z. Bone forming the socket of the eye.

N.B. - The same letters apply to each figure.

"Brewster found the following to be the refractive powers of the different humours of the eye, the ray of light being incident upon them from air: -

Aqueous humour .... 1.336 Crystalline lens, surface . 1.3767 „ „ centre . 1.3990

Crystalline lens, mean . . 1.3839 Vitreous humour .... 1.3394 Water....... 1.3358

"But the rays of light are not all incident upon them from the air, and as the rays refracted by the aqueous humour pass into the crystalline, and those from the crystalline into the vitreous humour, the indices of refraction of the separating surfaces of their humours will be -

From aqueous humour to outer coat of the crystalline . . 1.0455

From „ „ to crystalline, using the mean index 1.0352

From vitreous to crystalline, outer coat....... 1.0443

From „ „ „ using the mean index . . . 1.0332

"The eye, as already described, consists of four coats or membranes, which are disposed in the following order - viz., 1st, the sclerotic; 2nd the cornea, which fits into it like the glass of a watch; 3rd, the choroid; and 4th, the retina: of two fluids or humours, the aqueous and the vitreous, and of a lens called the crystalline.

"Over the cornea and sclerotic is expanded a delicate mucous membrane, called the conjunctiva. The iris is suspended across the eye, and in its centre is an opening, termed the pupil, which immediately opens when the light diminishes, and closes if the light is too strong. The posterior convexity of the lens is greater than the anterior. Sometimes, from a too great convexity of the lens or the cornea, the rays of light which enter the eye come to a focus before they impinge upon the retina, producing the defect called short-sighted vision. Optical science corrects this inconvenience by the use of a concave lens. If the crystalline lens is not sufficiently convex, the rays of light come to a focus behind the retina; this defect is surmounted by the use of a convex lens, which diminishes the divergence of the rays. Such ingenious artificial additions to the eye are common enough at the present day, but it may be asked, how did our forefathers bear these infirmities? Spectacles are supposed to have been unknown to the ancients, and it is stated by Francesco Redi that they vvere invented in the 13th century, between the years 1280 and 1311, probably about the year 1299 or 1300; he gave the honour of the discovery to Alexander de Spina, a monk of the order of Predicants of St. Catharine, at Pisa. Muschenbroek, the old electrician who discovered the Leyden jar, observes that it is inscribed on the tomb of Salvinus Armatus, a nobleman of Florence, who died in 1317, that he was the inventor of spectacles.

Continue to: