The Plan Of The Early Tudor House. Part 2

Description

This section is from the book "Early English Furniture & Woodwork", by Herbert Cescinsky, Ernest. R. Gribble. Also available from Amazon: Early English Furniture & Woodwork.

The Plan Of The Early Tudor House. Part 2

At a later stage we find the general plan alters from the open quadrangle to that of the "H" or "E" form. This development, however, does not materially affect our subject, whereas with the dwarfing of the hall and the origination of the Long Gallery, and such other private apartments, as the dining-room and the parlour, we get additional wall surfaces where some kind of covering, whether of tapestry or of wooden panelling, was necessary to comfort. With the Great Hall, of huge size and full house-height, any nakedness of wall, of rough stone or exposed brick, was not keenly felt, but as the home life of the family was transferred to smaller apartments, some means of finishing interior surfaces was found necessary, and panellings were the device generally adopted.

Fig. 23. Cothelstone Manor (1568). - South Front.

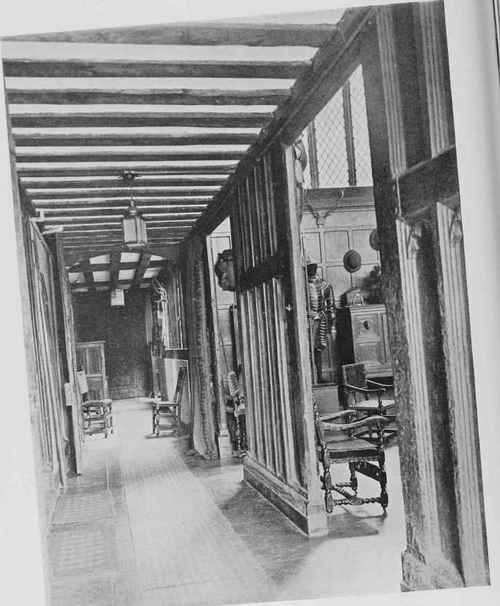

Fig. 24. Ockwells Manor. - View from the Screening into the Hall.

The usual furniture of the dais in the Great Hall was the so-called "refectory" table, - a type probably borrowed from the earlier monastic refectories, - generally of great length, seldom less than twelve feet. This was placed lengthwise on the dais, and behind it were the chairs of the lord and lady of the house, flanked on the other side by single stools or long benches. The body of the hall was occupied by several long tables of similar description to the one on the dais. Against the walls were the serving tables, one or two livery cupboards, and, at a later date, the enclosed two or three-tier " Standing" or "Court Cupboard." The floor of the recessed oriel in the hall was generally occupied by a large chest, usually erroneously called a marriage coffer, or dower chest. The true marriage coffer was smaller, and always reserved for the private apartment of the lady, as a receptacle for the household treasures in the way of linen or fabrics. Chairs were very rare pieces in these earlier " Great Halls," excepting as seats of state on the dais. The floor, generally of good honest flags, but sometimes of oak boards, was always left bare; the covering with strewn or plaited rushes being a later degree of effeminacy. The fireplace corresponded in size with the hall itself, the opening rarely less than eight feet in width by six in height, the hearth raised some four to six inches, and garnished with steel andirons and rails to support huge logs.

Fig. 25. Oak Screen In The Hall Of Wadham College, Oxford.

Fig. 26. Timber Roof In The Staircase Hall At Bablake Schools, Coventry.

In the earlier houses, as in the fourteenth-century Hall at Penshurst Place, the hearth was built in the centre of the Hall floor, upon which coupled raking andirons were placed, the fire, of huge logs, being built against these andirons. The Hall roof had a central outlet, or "smoke-loover," by which some of the smoke escaped, that is alter the hall itself was well filled and the inmates partially smoke-cured. At Penshurst the central hearth is octagonal, of large paving bricks with a flattened curb. It measures eight feet across. The smoke-louvre has been removed, although Joseph Nash, in " English Mansions of the Olden Time," shows it in situ in his drawing of Pen-hurst.

Fig. 27. Oak Staircase In Bablake Schools, Coventry.

On festivals, such as Yuletide, when the revels were high, and "horse play" the rule rather than the exception, the minstrels' gallery was the usual refuge of the ladies. At other times it was untenanted, its name being rather a complimentary than a practical one, the only chamber instruments being the older forms of the viol, or the more primitive kinds of sackbut, fife or tabor. The virginal, - the forerunner of the harpsichord and the piano, was of early Elizabethan introduction only, and of continental origin. The psaltery was rare at any time, in England, and was almost exclusively confined to the religious houses.

Fig. 28. Compton Wynyates (1520). - Plan.

Fig. 29. Compton Wynyates. - The West Front.

Next in progression from the monastic establishment and the mansion or castle, comes the Guild Hall, where the crafts united in giving of their best, both in design and workmanship, to the beautifying of their guild house. Sometimes, - as at St. Mary's Hall, Coventry, - very strong ecclesiastical influence is evident, but, when built under the shadow of the Church, these Guild Halls were generally constructed of stone.

Lavenham, on the other hand, which had a large woollen and textile trade with Flanders in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, has a purely secular Guild Hall, constructed of timber and plaster (generically known as "half-timber"). It is shown in its sadly restored condition, with numerous bay windows added, in Fig. 33.

This timber - and - plaster building was a favourite method throughout England from 1400 to 1550, especially in lesser houses of the superior yeoman, or small landowner type. It developed, in the direction of overhanging stories, the carving of visible joist ends, corner posts, barge - boards, mullions and door spandrils, to an extreme decorative limit. It is probable that this carving was not, in its entirety, executed when the house was built, but was added from time to time, as the owner found himself possessed of the necessary leisure or funds. It is impossible, otherwise, to account for the carving of every window mullion-member in tiny cottages at Lavenham (although a very prosperous town in the early sixteenth century) and elsewhere in East Anglia.

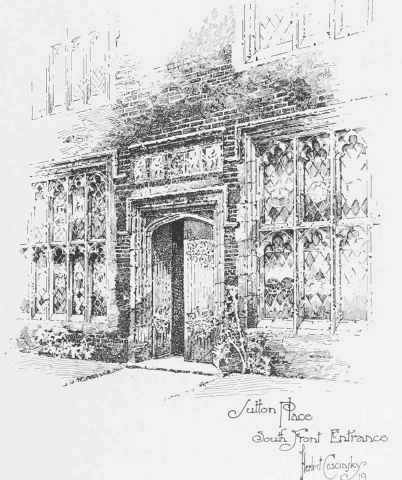

Fig. 30. Sutton Place (1523). - South Front Entrance.

Continue to: