Chapter II. How To Use The Tools

Description

This section is from the book "Our Workshop", by Anonymous. Also available from Amazon: Our Workshop.

Chapter II. How To Use The Tools

CARPENTRY, like every other important art, demands much attentive practice, before even a moderate degree of proficiency can be acquired. Any one accustomed to mechanical manipulation can tell whether a man is a skilled or an indifferent workman, by noticing the way in which he handles his tools. A novice thinks, when he sees an expert carpenter at work, that it requires no great skill to saw, to plane, or to bore a hole; and that any one can drive a nail or put in a screw. What we say is, let our tyro try his hand at any of these apparently easy jobs. He will very soon ask why the saw won't cut straight, or the plane make the wood flat; why, in boring the hole, the wood always splits, the nails goes askew, and the screw won't hold; and, we may add, our young friend discovers that carpentry is not so soon mastered as he thought.

The saw being the first tool the carpenter must use to reduce his materials to the rough dimensions, we will consider it first. On examination it will be observed that the steel or blade of the saw is thinner on the back than on the toothed edge. The object of this reduction in the thickness is to enable the saw to move with greater freedom in the kerf, as the saw-cut is called. If the blade were of the same substance from the front to the back edge, we should be unable to drive the saw after it had fairly entered on its work, owing to the great side friction. Another provision for still further facilitating the movements of the saw is called the set of the teeth. By this is meant the alternate side inclination of the teeth. By bending the teeth alternately to the right and left, they act more on the sides of the kerf, and make it wider than the thickness of the blade, which, being at liberty, can move freely. Setting a saw is a nice operation, and it requires much practice to do well. An amateur should never attempt to set or rather re-set his saws, as he will in all probability spoil them. If a saw be set more on one side than on the other, it will generally go astray on that side, and will require considerable attention to keep it to the line. The saw, if bought of a good manufacturer, will in all probability work quite satisfactorily; but we consider it necessary to point out the difficulties which may arise, and advise our pupils as to the best course to be pursued.

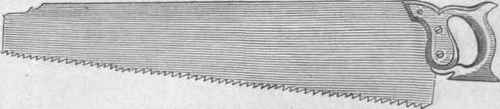

Suppose we require to make a rough box or any similar object, which is formed by fastening several boards together. The saw (fig. 2) must necessarily be used to reduce the wood to the right size, before we can be said to have commenced our task. The plank to be sawn is generally placed across two low stools or trestles about twenty inches in height. We must then mark a chalk or pencil line to indicate the path of the saw. If the plank be too wide for our purpose, the saw must be employed in the direction of the grain, or in the lengthway of the plank. The plank must overhang one of the trestles a few inches, and the saw, which is to be held in the right hand, can then be advantageously applied. You must stand a little behind the trestle which supports the overhanging end of the plank, and place your right knee on the plank to keep it steady. The first incision should be made with the small end of the saw, the strokes being short and quick. As the saw advances, the stroke may be increased, until almost the entire serrated edge comes into action. The overhanging end of the wood must be supported by the left hand, the fingers being below, the thumb alone resting on the upper side. The left hand is also employed to draw the plank forward when the saw approaches the trestle. The labour of sawing may be considerably diminished by occasionally greasing the blade with a tallow candle end, or the tallow may be smeared on a piece of leather, and so be more conveniently applied. Sawing with the grain is called ripping, and the tool employed for this purpose is called a rip-saw, the teeth of which are large and of a triangular shape. When you have ripped a sufficiently long piece of "stuff" to form the four sides of the box, supposing the plank to be long enough, the saw can be applied across the grain at right angles to the first kerf, the plank being held only by the left hand behind the new kerf. Just before the second kerf meets the first, the wood about to be severed must be supported by the left hand, and the saw must be used gently to avoid breaking a piece of the wood away when the kerfs meet. If care be not observed, a large piece or splinter will tear from either side, and perhaps unfit the wood for the purpose for which it was intended.

Fig. 2. - Hand-saw.

If the box is only to be made in the "rough," - that is, not planed, and simply nailed together, - you must saw the stuff as straight as possible, otherwise it will indeed be a rough job. If the plane is to be used, the wood must be sawn across for the sides after it has been planed, otherwise it will be more difficult to make the thickness uniform.

Sawing forms so important a part of the carpenter's work, that we may surely be excused if we dwell a little longer on the management of this tool. Our readers will do well if they practise sawing as extensively as their limited opportunities will admit.

If the plank be thick and the length to be sawn considerable, the work should be frequently turned over to equalize any irregularity that may arise from unskilful guidance of the saw. The work must therefore be marked out on both sides, care being taken to make the lines coincide with each other exactly, or they will be worse than useless.

While sawing, the eye must be vigilant, and should appreciate the slightest departure from the line. The eye must be directed only so much to the right or left of the edge of the blade, that the line may be seen on either side on the slightest movement of the head to the right or left. If the eye be suffered to wander, so that the line is seen entirely - say on the right - the hand will involuntarily force the saw in that direction, and the blade will pursue an erratic course. If the saw has not departed much from its proper course, it may be restored to the line by twisting the handle a little in the opposite direction to that which the saw has taken. We are enabled to do this the more readily owing to the set of the teeth, which has made the kerf a little wider than the blade, and the reduction in the thickness of the blade towards the back edge affords additional freedom. Care, however, must be observed in this correctional or steering process, otherwise the saw will be made to err as much in the opposite direction, and the blade may be jammed fast in the kerf.

Continue to: