Landing Over A Jump

Description

This section is from the book "The Horse - Its Treatment In Health And Disease", by J. Wortley Axe. Also available from Amazon: The Horse. Its Treatment In Health And Disease.

Landing Over A Jump

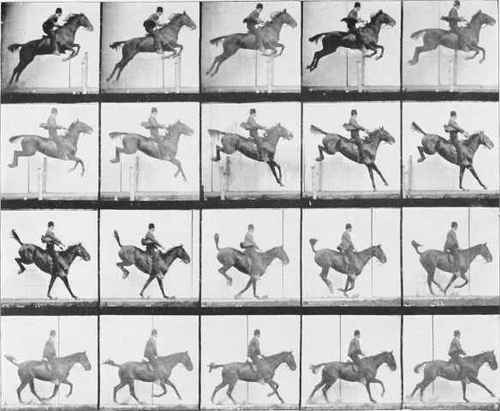

While suspended, the good jumper will tuck his feet up as closely as possible. No sooner do his hind-legs leave the ground than he thus prepares himself for anything that may happen; he may not be able to see the landing-place, and he is ready for a deep ditch or other contingency. The careless or untrained animal, on the other hand, drags his hind-legs behind him, and is liable to land upon the top rail of a fence, and cannot avail himself of an intermediate cat-like spring from it, or from the summit of a wall or other obstacle, which trick is a most valuable acquisition among the best of Irish horses and others accustomed to jump stone walls. Some of the best jumpers keep their limbs quite still while in mid-air, but there is no absolute rule, each horse caring for his own safety in the way which commends itself to his individual judgment. If we watch the trained performer at a distance, he appears to come down with both forefeet at once, but closer observation enables us to see that one foot is invariably in advance of the other, and receives practically all the weight, the other being slightly bent at the knee, and in readiness, in case of a false step, to save the horse from a fall. The leading leg is quite straight at the moment of landing, and a bent knee would seem to add greatly to the danger of a fall. (It is to be noted, however, that some of the safest conveyances the writer has had were a good deal "over" at the knee.) The right hind-foot follows the right fore, and the same thing applies to the limb of the other side. The print of the hind-foot is found to be in advance of the front one, so that the latter must be picked up and out of the way before the descent of the hind. In sticky ground, and for other reasons, such as a heavy rider rolling about in the saddle and supporting himself on the animal's neck, the fore-foot is not extricated in time, and a serious overreach may result. The forehand is raised after a jump by the straightening out of the limb, and anything that hinders the muscles engaged endangers both the horse and his rider. Severe bits have the effect upon tender-mouthed horses of making them try to land on their hind-feet, and in other ways risk losing their equilibrium. There are still persons to be found who believe that this is the habitual method (landing on the hind-feet), but, as pointed out by Hayes, " the hind-limbs of the horse are altogether unfitted to stand the violent shock which would be transmitted through them if they had to bear the weight of the body on landing. Such poor weight-carriers are they, that a horse disposed to rear has difficulty in walking a few yards on his hind-legs." Circus horses compelled to walk on their hind-legs have commonly large curbs, spavins, and thorough-pins.

The principal paces have now been alluded to; for further details and description of the artificial paces of the riding-schools, readers are referred to the works of Stanford, Hayes, Marey, Goubaux and Barrier, Le Coq, etc.

PLATE LXI. THE LEAP: SUSPENSION, LANDING, AND RECOVERY.

[ From Animals in Motion, published by Chapman & Hall. Copyright 1887 by Eadweard Muybridge.]

Continue to: