Characteristics Of Building Stone. Part 3

Description

This section is from the book "Notes On Building Construction", by Henry Fidler. Also available from Amazon: Notes on building construction.

Characteristics Of Building Stone. Part 3

Position In Quarry

In order to obtain the best stone that a quarry can furnish, it is often important that it should be taken from a particular stratum.

Mould.

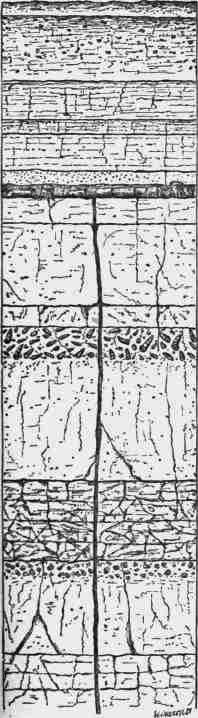

Clay and shingly matter; debris of Purbeck stone.

Slaty beds of stone.

Bacon tier, with layers of stone. Aish stone.

Soft Burr.

Dirt bed, containing fossil trees (Cycades).

Cap rising.

Excavated.

Top cap, 8 or 10 feet thick.

Scull cap.

Roach (true), 2 or 3 feet thick.

Blasted.

Whitbed, 8 to 10 feet thick.

Curf; flinty.

Curf and Basebed roach. Basebed stone, 5 or 6 feet thick.

Quarried by means of wedges and levers (no blasting).

Flat beds or flinty tiers.

Wedges, levers.

Fig. 1.

It frequently occurs that in the same quarry some beds are good, some inferior, and others almost utterly worthless for building purposes, though they may all be very similar in appearance.

To take Portland stone as an example. In the Portland quarries there are four distinct layers of building stone.

Fig.1 is a section showing approximately how the strata in a Portland quarry generally occur.

Working downwards, the first bed of useful stone that is reached is the True, or Whitbed Roach - a conglomerate of fossils which withstands the weather capitally. Attached to the Roach, and immediately below it, is a thick layer of Whitbed - a fine even-grained stone, one of the best and most durable building stones in the country; then, passing a layer of rubbish, the Bastard-Roach, Kerf, or Curf is reached, and attached to it is a substantial layer of Basebed.

The Bastard-Roach or Basebed-Roach and the Basebed are stones very similar in appearance to the True Roach and Whitbed; but they do not weather well, and are therefore not fitted for outdoor work.

Though these strata are so different in characteristics, the good stone can hardly be distinguished from the other even by the most practised eye.

Similar peculiarities exist in other quarries.

It is therefore most important to specify that stone from any particular quarry should be from the best beds, and then to have it selected for the work in the quarry by some experienced and trustworthy man.

The want of this precaution led to the use of inferior stone (though from very carefully chosen and good quarries) in the Houses of Parliament.

Seasoning

Nearly all stone is the better for being seasoned by exposure to the air before it is set.

This seasoning gets rid of the moisture, sometimes called "quarry sap," which is to be found in all stone when freshly quarried.

Stone should, if possible, be worked at once after being quarried, for it is then easier to cut, but unless this moisture is allowed to dry out before the stone is set, it is acted upon by frost, and thus the stone, especially if it be one of the softer varieties, is cracked, or, sometimes, disintegrated.

The drying process should take place gradually. If heat is applied too quickly, a crust is formed on the surface, while the interior remains damp, and subject to the attacks of frost.

Some stones (see p. 59) which are comparatively soft when quarried, acquire a hard surface upon exposure to the air.

Natural Bed, - All stones in walls, but especially those that are of a laminated structure, should be placed "on their natural bed," - that is. either in the same position in which they were originally deposited in the quarry, or turned upside down, so that the layers are parallel to their original position, but inverted. If they are placed with the layers parallel to the face of the wall, the effect of the wet and frost will be to scale off the face layer by layer, and the stone will be rapidly destroyed.

In arches, such stones should be placed with the natural bed as nearly as possible at right angles to the thrust upon the stone, - that is, with the "grain" or lamina? parallel to the centre lines of the arch stones, and perpendicular to the face of the arch.

In cornices with undercut mouldings the natural bed is placed vertically and at right angles to the face, for if placed horizontally, layers of the overhanging portion would be liable to drop off. There are, in elaborate work, other exceptions to the general rule.

It must be remembered that the beds are sometimes tilted by upheaval subsequent to their deposition, and that it is the original position in which the stone was deposited that must be ascertained.

The natural bed is easily seen in some descriptions of stone by the position of imbedded shells, which were of course originally deposited horizontally. In others it can only be traced by thin streaks of vegetable matter, or by traces of laminae, which generally show out more distictly if the stone is wetted.

In other cases, again, the stone shows no signs of stratification, and the natural bed cannot be detected by the eye.

A good mason can, however, generally tell the natural bed of the stone by the "feel" of the grain in working the surface.

A stone placed upon its proper natural bed is able to bear a much greater compression than if the laminae are at right angles to the bed joints.

Sir William Fairbairn found by experiment that stones placed with their strata vertical bore only 6/7 the crushing stress which was undergone by similar stones on their natural bed.1

Continue to: