Foreign Leaves

Description

This section is from the book "Tea, Coffee, And Cocoa Preparations", by Guilford Lawson Spencer . Also available from Amazon: Tea, coffee, and cocoa preparations.

Foreign Leaves

The addition of foreign leaves is best detected by means of the microscope. The leaf of the tea plant is quite characteristic in its venation, serration, and stomata. The veins recurve before reaching the border of the leaf and each forms a loop with its neighbor. The serrations are almost lacking in very delicate leaf buds, but are very distinct in the older leaves. Plates xxxiv and xl have been prepared to illustrate the leaf of the tea plant and other leaves which are said to have been

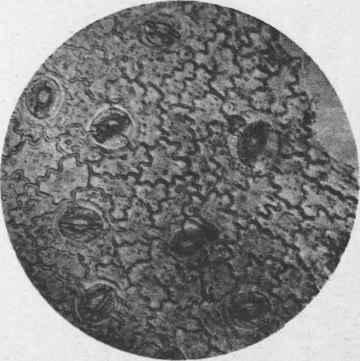

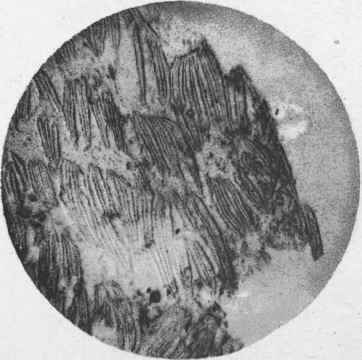

20393 -:No. 13 - 2 used in the adulteration of teas. These illustrations were prepared from photographic prints made; by the following simple method. The natural leaf was used in making an ordinary silver print, precisely as the photographer would employ a negative. The finished print was copied by a photoengraving process. Many of these illustrations show even the delicate veins of the leaves; the tea leaf, however, is quite fleshy, and did not yield a photographic print as distinct as those from the other plants. The lower epidermis of the leaf contains most of the stomata, which are surrounded by curved cells. There are few stomata in the upper epidermis. The stomata are shown in Plate XLI. Hairs are very numerous on the younger tea leaves, but sometimes entirely wanting in old leaves. They always contain theine. Dr. Thomas Taylor,1 in a report to the Department, mentions the presence of stone cells in tea leaves and states that his observations confirm those of Blyth in regard to the absence of these formations in certain leaves, viz, those of the willow, sloe, beech, Paraguay tea, ash, black currants, two species of hawthorn, and raspberry. Dr. Taylor also reports the presence of stone cells in the leaves of the Camellia Japonica, a plant related to the tea. Dr. Taylor prepares the sample of the leaf for examination by boiling three minutes with a strong caustic soda or potash solution. After the boiling a fragment of the leaf is placed on a slide under a cover glass and the latter is pressed down firmly with a sliding motion until the specimen is thin enough for microscopic examination. The stone cells appear as shown in Plate XLII.

Genuine Tea Leaves And Possible Adulterants Bull.NO.I3 Div.Of Chemistry. Plate XLI

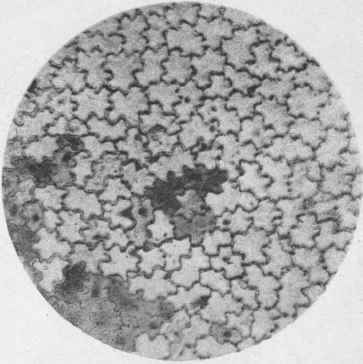

Tea Leaf x 115 Upper surface of epidermis.

Tea Leaf xll5

Lower surface of epidermis.

A.Hoen & Co. Heliocaustic .Baltimore

Bull.NO.I3 Div.Of Chemistry. Plate XLII

Stone Cell Of Tea Leaf Xll5

Seed Coat Of Coffee X55

"Coffee Flights."

A.Hoen & Co.Heliocaustic ,Baltimore.

In the general study of the serration and venation of a tea leaf the specimen should be steeped in hot water, and, after softening, the leaves should be unrolled and spread upon a glass plate for examination by transmitted light. Even small fragments of tea leaves will usually show some distinctive characteristic. In general in may be stated that a microscopic examination is only necessary in exceptional cases. In doubtful samples the stomata should be examined, and a search should be made for stone cells; the epidermis of both the upper and lower leaf should be examined. Even in the case of dust the microscope will furnish conclusive evidence as to whether it is from tea or some other plant.

According to Blyth2 every part of a theine-producing plant, even the minute hairs, contain this alkaloid. The writer cited employs the following method in examining a leaf fragment for theine:

The loaf or fragment of a leaf is boiled for a minute in a watch glass with a very little water, a portion of burnt magnesia of equal bulk is added, and the whole heated to boiling and rapidly evaporated down to a large-sized drop. This drop is transferred to a subliming cell, * * * and, if no crystalline sublimate be obtained when heated to 110° (a temperature far above the subliming point of theine), the fragment can not be that of a tea leaf. On the other hand, if a sublimate of theine is obtained it is not conclusive evidence of the presence of a tea leaf, since other plants of the camellia tribe contain the alkaloid.

1Annual Report of the Secretary, 1889, p. 192.

2Foods: Their Composition and Analysis, A. W. Blyth, p. 322.

Theine is detected under the microscope by the appearance of the crystals.

The ash of suspected leaves should he examined for manganese and potassium, since both these substances are always present in the tea leaf.

A low proportion of soluble ash is an indication of foreign leaves, since the ash of leaves suitable for use as an adulterant usually contains a low percentage of soluble matter as compared with that from tea. Facing renders dependence upon the proportion of insoluble ash rather uncertain, as this form of adulteration, if excessive, may increase the amount of insoluble mineral matter to a considerable extent.

A careful review of the methods of detecting foreign leaves shows the microscopic to be the only methods to be relied upon in all cases.

Continue to: